By Ray Hill

An imposing statue dominates the State Capitol in Nashville, yet few recognize the figure staring off into the distance, overlooking the street where he was murdered in downtown Nashville. Edward Ward Carmack was by profession a newspaperman, but he was also a successful politician, serving as a Congressman and U. S. Senator from Tennessee. Carmack’s talent for the written word was equaled by his ability to rouse crowds with his oratory. Still, it was his ability to eviscerate his enemies with his florid pen that would cause him to be left dead in a gutter.

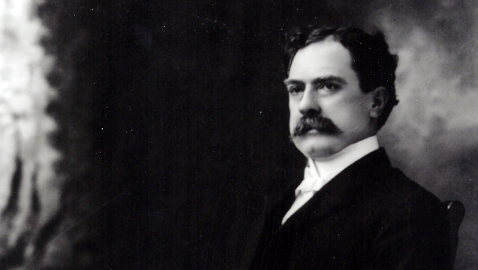

E. W. Carmack was born on November 5, 1858 in Sumner County, Tennessee and was the son of a preacher. Carmack attended the Webb School, quite a famous institution at the time and an ancestor of Knoxville’s own Webb School. Carmack, like many others of his generation, “read” the law before being admitted to the Bar to practice. Carmack moved to Columbia, Tennessee where he became the City Attorney when just twenty-three years of age. Carmack’s upward political progression continued with his election to the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1884 when he was twenty-six.

Carmack soon discovered practicing law was anything but a labor of love and he found his true calling when he joined the staff of The Nashville Democrat in 1889. E. W. Carmack eventually became editor-in-chief when The Democrat merged with another Nashville newspaper, The American. Carmack soon became widely recognized as a bitterly partisan Democrat and was noted for his vitriolic editorials castigating those he felt deserved his condemnation in vivid terms. Carmack’s use of the English language was as colorful as his own red hair and his ability to denounce those of whom he disliked or disapproved was so strong that he was challenged to a duel at least once. Carmack readily accepted the challenge to duel, but both he and his adversary were arrested before they could attempt to kill one another.

Carmack left The American to assume a similar position for The Memphis Commercial, which was later to become The Commercial Appeal. By that time, Carmack’s forceful editorials had already brought him the kind of attention to warrant many Democrats to consider him as a serious candidate for public office. There was even talk of Carmack running for governor.

It was not long before E. W. Carmack did indeed become a candidate for office, running for Congress in 1896 against incumbent Congressman Josiah W. Patterson. The Carmack – Patterson rivalry would last the remainder of E. W. Carmack’s life and encompass two generations of the Patterson family. That same political feud would also eventually lead to Carmack’s death.

Carmack had decided to run for Congress after having taken up the cause of “free silver” in his newspaper. The national Democratic Party would become sharply divided over free silver versus the gold standard and those Democrats who espoused the cause of free silver would be anathema to “gold bug” Democrats. Free silver’s most notable spokesman was William Jennings Bryan, then a young Congressman from Nebraska, whose dramatic “Cross of Gold” speech electrified so many delegates at the 1896 Democratic National Convention, he was nominated to run for president against Republican William McKinley.

At a time when virtually all news reached the public via print media, E. W. Carmack had a shrewd understanding of manipulating events and when he resigned as editor of The Commercial Appeal, he made it appear he was resigning as a martyr to the cause of free silver. The truth was Carmack had already determined to be a candidate for Congress and had very strained relations with several members of his editorial board. Carmack had a flair for the dramatic and was not above using it for his own political advantage.

Both E. W. Carmack and Congressman Patterson were nominated to run for Congress by convention and both claimed to be the legitimate nominee of the Democratic Party. Congressman Patterson was a supporter of the gold standard, a position that was not entirely popular inside his own party with rank and file members, but was seen as logical and sane by many businessmen. Patterson’s nomination came from what many Democrats perceived to be a gold bug dominated primary. Carmack was nominated by a convention of Democrats and U. S. Senator Isham G. Harris came to Memphis to preside over that convention, giving it a stamp of legitimacy it would not have had otherwise.

When presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan came to Memphis to speak, he gave his endorsement to Edward W. Carmack, an endorsement that was especially helpful to the congressional candidate in the counties outside of Shelby County.

The contest between Carmack and Congressman Patterson was brutal; Patterson carried Shelby and Tipton Counties, but E. W. Carmack won such large majorities in Hardeman and Fayette Counties that he emerged as the winner by about 365 votes. Congressman Josiah Patterson did not concede the election readily; in fact, he did not concede at all. Patterson challenged the election results, perceiving he might have an advantage inasmuch as the Republicans would be in control of the Congress and the GOP strongly supported the gold standard.

Congressman Patterson’s decision to contest the election results caused E. W. Carmack to seek the best legal counsel possible to represent him. He went to the firm of Carroll and McKellar. Colonel William Carroll was one of the most respected attorneys in Memphis and a very successful one. He was also a cousin to E. W. Carmack’s wife and when Carmack approached him to represent him, Colonel Carroll turned him down.

In his book “Tennessee Senators”, future U. S. Senator Kenneth D. McKellar, relates his partner Colonel Carroll immodestly told Carmack, “No, Ned, I cannot do it. I have a great reputation as a lawyer which I want to preserve intact. I am unwilling to take a case I know in advance I am going to lose.”

Colonel Carroll suggested Carmack go across the street to visit another lawyer, but as the dejected Carmack was leaving the office Carroll hurried after him, yelling, “Ned, come back here! I have changed my mind. I will take your case and turn it over to Mr. McKellar to try. He has no legal reputation to lose.”

Senator McKellar was quite amused by the story and repeated it often. McKellar went to Washington, while Carmack went to Nashville to attempt to sway legislators who were electing a new United States senator for Tennessee, as Isham G. Harris had died. McKellar addressed the House committee hearing Patterson’s contest and later wrote that the Chairman of the committee, a former Confederate general who had become a Republican, invited the young Memphis attorney to join him for lunch. McKellar and General Walker lunched in the Senate restaurant and in his book McKellar mentioned it was the first time he ever saw the Senate restaurant. Congressman Walker told McKellar he was quite impressed with his argument before the committee and had decided he would send a report to the full Congress favoring E. W. Carmack being seated, if his colleagues agreed with his own position. Walker did wonder why Carmack had been absent and suggested Carmack would be better served by being in Washington, D. C. than Nashville.

McKellar promptly sent a telegram to Carmack saying he believed the committee would likely decide in his favor. Carmack replied, “Telegram received. Who in Hell has been filling you up on rut-got liquor since you got to Washington? E. W. Carmack”

Carmack clearly believed he had no chance to be seated due to Josiah Patterson sharing the same fondness for the gold standard as most Republicans. Carmack was not surprised when both the elections subcommittee and full committee recommended overturning the results of the election and seating Congressman Patterson. The issue went to the floor of the House of Representatives and both Patterson and Carmack were given the opportunity to present their own case to the members. Patterson spoke eloquently, but Carmack gave what many considered to be the best speech of his career. It was a remarkable performance and the House did not follow the recommendations of its own committees, but instead voted to seat E. W. Carmack.

Carmack was easily reelected to Congress in 1898 and by 1900 was the leading candidate to replace Senator Thomas B. Turley who was not seeking to be reelected by the Tennessee General Assembly. Two of Tennessee’s most popular politicians both coveted the Senate seat as well; Robert Love Taylor had served three times as Tennessee’s governor and was anxious to go to Washington. Benton McMillin had served in Congress for twenty years before being elected governor and he, too, very much wanted to go to the Senate. Taylor never openly announced himself as a candidate for the United States Senate, but Governor McMillin tried hard to garner enough support to be elected. Eventually all potential opponents withdrew and E. W. Carmack was elected.

Edward Ward Carmack was at the peak of his influence, but he inflicted serious political injury upon himself when he helped to engineer the election of Governor James B. Frazier to the United States Senate following the death of Senator William B. Bate. Senator Bate had just been reelected to a fourth term, but died five days into his new six-year term. Frazier himself had just been reelected governor and both Robert L. Taylor and Benton McMillin still harbored senatorial ambitions. Carmack successfully helped Frazier to secure enough votes in the General Assembly before either McMillin or Taylor could mount a serious campaign. Both Taylor and McMillin were furious and Taylor decided to challenge Carmack for reelection in 1906.

While U. S. senators were still elected by state legislatures at the time, Tennessee Democrats had a nonbinding preferential primary in 1906. Both Senator Carmack and former Governor Taylor campaigned hard, with Taylor finally winning a narrow victory.

Carmack only carried Memphis of the big urban areas, but he remained highly popular in many of Tennessee’s more rural communities. Senator Carmack accepted his defeat for reelection graciously and it was not long before the lure of politics tugged at him once again. Carmack decided to run for governor in 1908 and it promised to be an exceptionally bitter contest. The incumbent was Malcolm Rice Patterson, the son of Carmack’s old foe Josiah Patterson. Malcolm Patterson had succeeded Carmack in Congress before getting himself elected governor in 1906.

Obviously Malcolm Patterson resented Carmack having defeated his father and the gubernatorial race quickly became as personal as it was bitter. Carmack was a strong proponent of prohibition while Governor Patterson was both personally and politically “wet”. The gubernatorial campaign was waged as a referendum on the prohibition of liquor and spirits. Patterson was denounced by Carmack as a tool of the liquor lobby and neither side spared the other in a campaign of invective remarkable even for the turbulent politics of Tennessee.

Patterson carried the urban areas to clinch the nomination in a narrow victory and it was a devastating defeat for Edward Carmack. Following the election, Carmack accepted an offer from Luke Lea, owner and publisher of The Nashville Tennessean to become the paper’s editor.

It was not long before Carmack was again hurling editorial thunderbolts at his enemies, Governor Patterson and friends of Patterson’s administration. Not all of the victims of Carmack’s editorials accepted them meekly. Colonel Duncan B. Cooper objected strongly to Carmack’s attacking him and warned the editor there would be serious consequences should he continue to defame him. Carmack’s friends became so concerned about the reaction to his editorials, they feared for his life. So too did Carmack and he began carrying a gun while traversing the streets of Nashville.

E. W. Carmack was not the only one carrying a gun and he encountered Colonel Cooper and Cooper’s son Robin on a Nashville street. Carmack drew his weapon and fired, wounding Robin Cooper. The younger Cooper proved to be a much better shot and returned fire, killing the editor instantly. Carmack fell dead into the gutter, a pool of blood forming around his body.

The murder of E. W. Carmack so outraged Tennesseans it eventually forced Governor Malcolm Patterson out of office. It also gave Carmack the aura of a martyr and the legislature erected the impressive statue of Edward Ward Carmack that still stands today.