Camille McGee Kelley, judge of the Shelby County Family Court, was a jewel in the crown of the Memphis machine of Edward Hull Crump. At the time of her appointment in 1920, Kelley was only one of two female judges in the South and the only woman to sit as a juvenile court judge.

Kelley was highly popular in Memphis and Shelby County, an easily recognizable figure in her trademark dresses, furs and a large flower always pinned to her chest. Kelley looked precisely like what she was: a friendly, well-to-do grandmother who was somewhat smug and condescending in freely dispensing her maternal wisdom to anyone who would listen.

The Memphis Boss was always highly sensitive to the attacks of opponents on his political machine and Crump countenanced no graft or corruption from his subordinates. At the first hint of corruption, Crump moved with alacrity in removing the offender from office. Yet the reign of the matronly juvenile court judge would prove to be one of the worst cases of corruption in modern Memphis history and a sore embarrassment to Crump.

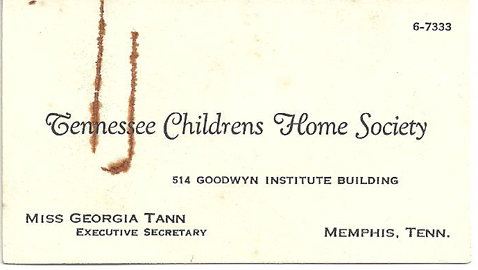

One cannot detail the life and service of Judge Camille Kelley without relating the history of Miss Georgia Tann, who operated the Tennessee Children’s Home Society. Miss Tann would have a powerful, albeit malevolent, influence upon adoption of children. Like Judge Camille Kelley, Miss Georgia Tann had a matronly and benign appearance and no less than First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt believed her to be an expert in the field of childcare. Perhaps no one in the State of Tennessee had more to do with the confidentiality laws adopted by the General Assembly than Georgia Tann. Miss Tann used those laws to her advantage and apparently destroyed, altered or otherwise tampered with birth records to the extent where it became impossible to determine the parentage of thousands of children.

Miss Georgia Tann turned adoption into a money-making enterprise and at a time when adoptions in Tennessee cost the princely sum of $7, some adoptions brokered by Tann cost as much as $5,000, roughly the equivalent of $84,000 in today’s currency. Miss Tann operated her Tennessee Children’s Home Society before the extensive welfare state existed in this country; there was little in the way of support, financial or otherwise, single mother’s could count on at the time.

Crump’s Memphis was well run and Memphis won numerous awards for its cleanliness, safety, etc., yet one statistic likely vexed the Boss; it had the highest infant mortality rate in the country.

Miss Georgia Tann was born in 1891, the daughter of a judge in Mississippi. Georgia was a nonconformist at an early age, altering her name from Beulah George Tann to the more feminine “Georgia.” Georgia was not an especially attractive woman and she displayed little interest in settling down and marrying. Instead, Georgia Tann pursued one of the few avenues available to women who wished to become professionals in that era: social work. It not only afforded Georgia the opportunity for a career, but a means to escape from her home and her domineering father.

Miss Tann rapidly concluded poor people could not possibly be fit parents. Her comments about poor people having children were both cruel and derisive; Miss Tann referred to them as “breeders” and the mothers as “cows.”

When Miss Georgia Tann embarked upon her unfortunate career, adoption was hardly a common practice. She would refine it to an art form and one that paid handsomely.

Miss Tann was hired by the Mississippi Children’s Home-Finding Society and she began finding homes for children, but soon discovered there were men and women who were nothing less than desperate to have a child and they were willing to pay. Miss Tann visited the home of a poor young widow named Rose Harvey, who lived in a cabin in Jasper, Mississippi. Rose was ill, suffering from diabetes, and pregnant. Her two-year old son, Onyx, was playing on the porch when Georgia Tann arrived and took the little boy. Rose’s father was convinced to sign legal documents stating his daughter was an unfit mother and had abandoned Onyx. The brown-haired, brown-eyed little boy was given to another family and even though Rose managed to hire an attorney, she could not get her child back.

It was that same year that Georgia Tann adopted a child herself; Miss Tann adopted a baby girl whom she named June. Quoted in Barbara Raymond’s book about Miss Georgia Tann, June’s daughter Vicci said, “Mother said Georgia Tann was a cold fish; she gave her material things, but nothing else. I don’t why she bothered to adopt her.”

By 1924, Miss Georgia Tann was in Memphis, Tennessee and started the Tennessee Children’s Home Society. In time, some of the wealthiest couples in the country would adopt babies from Georgia Tann. Several movie stars adopted babies from Miss Georgia Tann, including Joan Crawford, Lana Turner, and Dick Powel and his wife, June Allyson. Governor and Mrs. Herbert Lehman adopted a baby from Georgia Tann; Lehman was the lieutenant governor to Franklin D. Roosevelt and FDR’s successor. He was also enormously wealthy, being the heir to Lehman Brothers.

Georgia Tann owned considerable property and purchased a home in Memphis at 91 Stonewall Street, a comfortable bungalow type structure of some 2,200 square feet, three bedrooms and two baths. Miss Tann lived there with her partner, Ann Atwood Hollinsworth. Tann officially adopted Mrs. Hollinsworth in Dyer County a few years before her death. Mrs. Hollinsworth had a son, Jack, who was killed in an American Airlines plane crash in 1943. Mrs. Hollinsworth would outlive her partner by almost fifty years, dying in 1995.

Once a baby was in Miss Tann’s custody, she would alter the birth records beyond all recognition and create a more acceptable story accounting for the baby’s birth, which was calculated to appeal to prospective adoptive parents. Rather than simply being the child of a single mother or poor couple, the baby was the result of a brief union between a young mother of good breeding and her boyfriend of equally social standing. Miss Tann was not above creating a background for a particular child to suit prospective adoptive parents.

Georgia Tann’s personal appearance likely actually aided her in concealing her true nature. A rather dumpy woman, who usually looked rather rumpled, looked like anything save for the aristocrat she pretended to be. Her graying hair was cut short and seemed only haphazardly styled. Miss Georgia Tann looked quite innocuous; she did not seem in any way threatening. She appeared to be an inoffensive middle-aged woman and likely looked precisely like what many perceived to be a professional social worker.

Miss Tann, for all her faults and loathsome nature, was quite shrewd. She employed Abe Waldauer, a high-ranking member of the Crump machine, as her attorney. In Memphis, Waldauer was extremely well connected and he proved to be an effective ally in lobbying the Tennessee General Assembly. Waldauer was sympathetic to Miss Tann, as he was an adoptive father himself. Miss Tann’s first contact with Abe Waldauer seems to have been in 1933 when she wanted the lawyer’s help with her invalid brother. Georgia Tann wrote a petulant letter to Waldauer on January 28, 1933, complaining, “I have tried several times recently to see you and talk with you in regard to my brother’s claim against the government.”

Eventually Waldauer became both Georgia Tann’s personal attorney as well as that of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society. The Board of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society included some of the “best” people in Memphis; Walter Chandler would go on to serve as Congressman from the district, as well as Mayor of Memphis. John Reichman was a former Shelby County sheriff and Mrs. E. W. Hale was the wife of the head of the Shelby County Commission. The famous author Pearl Buck even wished to collaborate on a book with Georgia Tann. Yet some suppose E. H. Crump knew exactly what Miss Tann was doing and she somehow enjoyed his personal protection. It seems unlikely she fooled practically everybody save for Boss Crump.

And Miss Georgia Tann had a lot of people fooled.

Georgia Tann helped to formulate the laws on adoption in Tennessee, some of which exist to this day. Due to the nature of her business, it was imperative to Miss Tann that adoption records remained confidential and closed. Miss Tann was quite secretive and there appear to be instances where she even deceived her own lawyer. Georgia Tann would contact Judge Kelley with a list of changes in Tennessee’s laws which she believed needed to be changed. Judge Kelley would then send the list on her own stationery to Abe Waldauer, giving Waldauer the notion those changes were requested by Judge Kelley and the Shelby County Family Court.

Many of the children given up or sold for adoption by Miss Georgia Tann were fortunate enough to find loving homes, but there were many who were far less lucky. There were numerous stories of birth parents and mothers who literally spent their entire lives trying to locate their lost children.

Miss Tann conceived the idea of placing ads in local newspapers, complete with a photograph of a child well scrubbed and nicely dressed under the headline, “Want A Real Live Christmas Present?” Another featured a smiling little boy grasping a ball under the headline, “Yours for the Asking!”

The advertisement, which ran in the Memphis Press Scimitar on December 8, 1935, read:

“Yours for the asking!

“George wants to play catch but needs a Daddy to complete the team. ‘Catch this ball, Daddy!’ How would YOU like to have this handsome five-year old to play ‘catch’ with you? How would you like his chubby arms to slip around your neck and give you a bear-like hug? His name is George and he may be yours for the asking, if you hurry along your request to the Christmas Baby Editor of the Press-Scimitar.

“In cooperation with Miss Georgia Tann of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society, the Press-Scimitar will place 25 babies for adoption this Christmas.”

Even the local newspapers believed they were rendering a real service to the children by finding them loving homes.

Like Judge Kelley, Miss Georgia Tann was actually lauded by an unsuspecting population for what most believed to be her good work. National publications referred to her as “the foremost leading light in adoption laws” in the country. Eleanor Roosevelt actually sought Miss Tann’s advice on issues regarding child welfare and President Harry Truman invited her to his inauguration. If anything, Miss Georgia Tann was outwardly respectable.

Miss Tann’s alliance with Judge Kelley gave her enormous power. Armed with not only the power of the court, Miss Tann had the resources at her command from the Memphis Police Department and the Shelby County’s sheriff’s office through Judge Kelley. There is good reason to believe Judge Kelley was paid by Miss Georgia Tann for her cooperation.

By the 1940s, some uncomfortable questions were being asked. Miss Tann owned considerable property, including a motel, a large farm and home named “Tannwood” and was driven about town in a chauffeured Cadillac limousine. Evidently folks were encouraged to believe Georgia Tann came from a prominent and wealthy Mississippi family, so fewer eyebrows were raised than might have been the case otherwise. Very few social workers had the means to employ a chauffeur who actually wore a uniform.

The Crump machine suffered devastating defeats in the 1948 elections. Crump refused to support Senator Tom Stewart for reelection that year, preferring instead to back Cookeville Judge John A. Mitchell, whom the Memphis Boss had never even met. Crump’s political partner, Senator K. D. McKellar, tried to change Crump’s mind, but was unsuccessful. Senator McKellar did not believe Judge Mitchell was a strong candidate, a reality that became more abundantly clear as the Democratic primary approached. Both McKellar and Crump were backing incumbent Jim Nance McCord for the gubernatorial nomination in 1948, but Governor McCord was mortally wounded by having instituted a sales tax for education. Tennesseans apparently less appreciated the free textbooks for their children than they resented the new tax. McCord was opposed by former Governor Gordon Browning, a long-time opponent of both Crump and McKellar. The election of Gordon Browning and Estes Kefauver in the Senate race ended the long domination of Tennessee politics by Senator McKellar and E. H. Crump.

The whispers surrounding Miss Georgia Tann’s Tennessee Children’s Home Society soon reached the ears of Governor Browning. The governor realized were the allegations true, it would be a profound embarrassment to Crump and his machine. Browning authorized an investigation and announced the findings at a press conference. They were both appalling and devastating.

The focus of Governor Browning’s comments had less to do with the children, their parents or the theft of babies than profiteering illegally while the Tennessee Children’s Home Society received state funding. Browning’s choice to lead the investigation was attorney Robert L. Taylor (later for years a federal judge sitting in Knoxville) who termed many of the adoptions by Georgia Tann as “mail order adoptions”. Taylor’s report revealed some judges in Memphis had urged that the Tennessee Children’s Home Society be investigated years ago. Georgia Tann’s operation had also been investigated by John Brown, U. S. Attorney for the Western District of Tennessee and a McKellar appointee. Brown’s probe clearly indicated adoptive parents were being seriously overcharged for investigation and transportations costs. Tennessee’s Commissioner of Welfare had concluded that more than 1000 babies sent to New York and California had cost the parents perhaps as much as $1,000,000, a sum roughly equivalent to approximately $9,700,000 in today’s dollars.

Ironically, Miss Georgia Tann was by that time outside the reach of the law. Within days of the governor’s press conference, Georgia Tann died from cancer inside her home and in the comfort of her own bed. Tann died from uterine cancer and strangely had never sought any kind of treatment. Death came for her before the law could.

Camille Kelley, for thirty years judge of Shelby County’s Family Court, quickly announced she was resigning for reasons of health. It was readily apparent Crump had forced her resignation from the bench. Past seventy at the time, Judge Kelley also escaped prosecution, retiring quietly and living with her son, where she died from a stroke in 1955.

The victims, the children adopted out to families across the country, were only granted the right to view their birth certificates and records of their adoptions by the State of Tennessee in 1995. Some were reunited with members of their families and some are still looking to this day.