From the author’s personal collection.

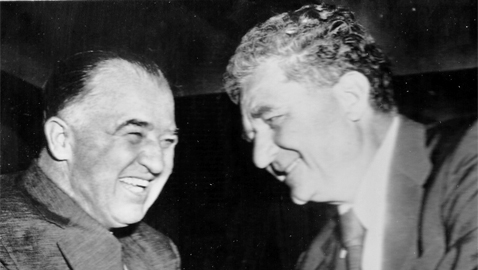

Governor A. B. “Happy” Chandler with Ohio Governor Frank J. Launch in 1956.

Governor Albert B. “Happy” Chandler had badly lost his bid to defeat Senator Alben W. Barkley for the United States Senate in 1938. The death of Kentucky’s other senator, Marvel M. Logan, gave Chandler the opportunity to go to the Senate. Chandler resigned as governor and a day later his successor appointed him to the vacancy. The former governor’s ties to Virginia senator Harry F. Byrd helped him to get an assignment to the Military Affairs Committee.

The first thing Senator Chandler had to do was get elected, as he had to run in a special election in 1940 for the remaining two years of the late Senator Logan’s term. It is a historical fact that governors who leave office to have themselves appointed to the United States Senate rarely fare well in elections. Happy Chandler’s popularity, despite losing to Alben Barkley, remained intact and he defeated his challenger in the 1940 Democratic primary with better than seventy percent of the vote. Senator Chandler went on to win the general election against Republican Walter B. Smith with over fifty-eight percent of the vote.

Happy Chandler’s voting record while in the United States Senate resembled that of many Southern Democrats. Chandler voted against an anti-lynching bill, which predictably highly upset many African-American constituents.

Senator Chandler had to run for reelection again in 1942 for a full six-year term and faced opposition in the Democratic primary from former Congressman John Y. Brown. Brown had been incensed by then-Governor Chandler’s refusal to support him for the U. S. Senate in 1936.

Brown was the father of a future governor of the same name. He served, off and on, in the Kentucky House of Representatives for decades and had once allied himself with Happy Chandler to defeat Governor Ruby Laffoon’s proposed sales tax. Brown had been elected to Congress statewide in 1932, to an At-Large seat. He had run for governor in 1939, but lost the Democratic primary.

Brown’s challenge to Senator Chandler amounted to little, as he garnered less than thirty percent of the vote. 1942 was a bad year for many incumbent Democrats and while Happy Chandler’s share of the vote fell slightly, he easily defeated Republican Richard Colbert.

John Y. Brown would remain a force in Kentucky politics for years to come, but he never lost his animosity toward Happy Chandler. Brown would attain the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate, but many of Chandler’s supporters quietly backed Republican John Sherman Cooper, who won the general election.

After winning reelection, Senator Chandler left for a worldwide tour as part of the Senate’s Military Affairs Committee. Upon his return to Washington, Senator Chandler began to think of national politics and attempted to boost himself as FDR’s vice presidential running mate in 1944. Chandler’s national aspirations hit a bump when many of Kentucky’s most powerful politicians refused to support him for the vice presidential nomination. Earle C. Clements was a rising power in Kentucky’s Democratic Party.

Clements and Chandler had long been at odds; Clements had managed the gubernatorial campaign of Thomas Rhea against Happy Chandler in 1935. The two never seemed to be on the same side since. Clements was elected to Congress in 1944, while Happy Chandler had to be content to remain in the United States Senate.

The bitterness between the two men escalated following the 1944 Democratic National Convention. Harry Truman received the vice presidential nomination and succeeded to the presidency when Franklin Roosevelt died. Happy Chandler believed that he could have been nominated and succeeded to the presidency himself had it not been for Earle Clements.

Death always plays a part in the ebb and flow of politics and it was the death of Kenesaw Mountain Landis that saw a change in the life of Albert B. Chandler. Landis was the formidable judge who was baseball’s first Commissioner. It was Judge Landis who expelled eight players in perhaps the first real scandal in baseball. The “Black Sox Scandal” was notorious during its time and the forbidding Judge Landis took matters into his own hands and dealt with it with finality.

Judge Landis’ decisions as Commissioner of Baseball were not always universally hailed; many believed he had been unduly harsh with some involved in the Black Sox Scandal. Others faulted Landis for long delaying the desegregation of baseball.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis suffered a heart attack while keeping his ill wife company in the hospital in October of 1944. The judge was thought to be improving and the baseball team owners voted to extend Landis’ contract as Commissioner of Baseball for another seven years the next month. The 25th of November the seventy-eight year old Judge Landis died.

Selecting a successor to the legendary Judge Landis proved to be a difficult task. The team owners considered the possibility of hiring a Commissioner who had the requisite skills to navigate the treacherous rapids of politics. In 1945, members of the United States Senate earned around $10,000; the Commissioner’s post paid $50,000, which was a considerable enticement to Senator Happy Chandler.

Chandler was hardly the only politician to be considered as the new Commissioner of Baseball; in retrospect, there seemed to be hardly anyone who was not considered. Ohio had two potential candidates to be Commissioner of Baseball; Senator John W. Bricker, a Republican and Governor Frank J. Lausche, a Democrat. Both Bricker and Lausche had been talented athletes in their youth and received consideration as the new Commissioner of Baseball. James A. Farley, for eight years FDR’s Postmaster General and Chairman of the National Democratic Party was rumored to be under consideration, as was Robert Hannegan, President Truman’s Chair of the National Democratic Party and Postmaster General. Even FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was reputedly considered to be Baseball Commissioner by the team owners.

The initial front-runner for the post had apparently been Ford Frick, president of baseball’s National League. Frick’s candidacy encountered stiff opposition from Philip Wrigley, the chewing gum magnate who owned the Chicago Cubs. Wrigley’s own opposition to Frick was augmented by equally strong opposition by Warren Giles, the owner of the Cincinnati Reds; Larry McPhail, a co-owner of the New York Yankees, began promoting the candidacy of Senator A. B. Chandler.

The team owners gathered in Chicago on April 24, 1945 to consider a replacement for the late Judge Landis and Happy Chandler’s name was evidently not even on the short list of candidates. Deadlocked, the owners took an informal vote and Chandler was amongst the top three candidates. After further balloting, Happy Chandler received enough votes from the owners to become the next Commissioner of Baseball.

Despite his election as Commissioner of Baseball, A. B. Chandler remained in the United States Senate until resigning on November 1, 1945. Chandler’s election as Commissioner of Baseball was not widely acclaimed by many sports writers, especially in the east and northeastern region of the country. Chandler’s homespun style and folksy ways seemed to irritate them and they mocked the former senator relentlessly. The fact he was a Southerner certainly did not sit well with them either.

When Happy Chandler relocated the Commissioner’s office from Chicago to Cincinnati, those same sports writers were livid. Cincinnati was of course much closer to Chandler’s home in Versailles, Kentucky.

Perhaps the most famous event to occur during A. B. Chandler’s tenure as Commissioner of Baseball was the introduction of black players in the profession. Jackie Robinson had been signed to play baseball by Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Jackie Robinson’s signing and career was the subject of a recent movie, “42”. Rickey had signed Robinson to play just prior to Happy Chandler’s election as Commissioner of Baseball.

Robinson’s contract was actually with the Montreal Royals and he was in fact the first black to play for a major league affiliate. Rickey transferred Jackie Robinson from Montreal to the Brooklyn Dodgers. There was heated debate amongst the team owners about allowing a Negro to play baseball in the major leagues. Evidently Ford Frick was strongly against the idea and at a meeting of team owners, Frick got the owners to ratify his contention black players would be a significant threat to the institution of professional baseball. Happy Chandler later recalled that Branch Rickey came to his home and Bowie Kuhn, himself later Commissioner of Baseball, credited Chandler with breaking the color barrier in the sport of baseball.

In the first place, A. B. Chandler held the power as Commissioner to negate Jackie Robinson’s contract, but instead he chose to approve it. When Robinson had to endure vile racial epithets and taunts from Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman and his players, Commissioner Chandler personally intervened and pledged to discipline them for their behavior if it continued. Some members of the St. Louis Cardinals threatened to go on strike because of Jackie Robinson being allowed to play and once again, Happy Chandler was decisive. He made it quite clear he would support Ford Frick’s promise to suspend any player who attempted to strike.

It was Happy Chandler who created the first pension fund for baseball players, just as he had been responsible for creating the first pension fund for educators in Kentucky during his term as governor. Chandler sold the rights to broadcast the World Series in 1947 and used the money for the purpose of starting the pension fund.

Still, not everybody was happy with Chandler. Commissioner Chandler’s contract still had almost three years left to run when he sought to have the team owners extend it at the end of 1949. The vote went against offering Chandler an extension of his contract, although the owners promised to consider the issue the following year. When the time came to consider Chandler’s request for an extension, he did not get the three-fourths majority required. Disgusted, A. B. Chandler resigned as Commissioner of Baseball on July 15, 1951.

Even during his time as Commissioner of Baseball, A. B. Chandler kept his hand in Kentucky politics. Chandler’s political foe Earle C. Clements had left Congress to run for governor in 1947 and had been elected. Clements resigned the governorship in 1950, as he had been elected to the United States Senate. Clements’ successor was Lawrence Wetherby, who had been lieutenant governor. Wetherby was a candidate for a full four-year term in 1951. A. B. Chandler spent the next four years plotting his return to public office.

To the surprise of virtually no one, A. B. Chandler announced himself as a candidate for governor in 1955. It had been twenty years since his first election as governor and Senator Clements had a hard time settling on a candidate formidable enough to beat Chandler in the Democratic primary. Eventually, Clements decided to back Bert T. Combs, a judge on Kentucky’s Court of Appeals, for the gubernatorial nomination.

Happy crisscrossed Kentucky, poking fun at “the Little Judge” as well as Senator Clements and Governor Wetherby, whom he referred to as “Clementine and Wetherbine”. Chandler dismissed Combs as nothing but a puppet for Senator Clements and Governor Wetherby.

Bert Combs was a novice at the art of politics and his first speech during the primary campaigned showed it. Reading from a text, Combs dryly confessed it was quite possible it was time for Kentucky to reinstitute the sales tax. That admission gave Happy Chandler ammunition to point out he had repealed the hated sales tax during his first administration as governor. Chandler promised he would not raise taxes and accused Combs of intending to increase taxes.

While Bert Combs was a neophyte to politics, Happy Chandler remained a master of the art of politics and had fun with even the smallest of things. Noting that the governor’s office had been paneled with African mahogany, Happy told audiences he was astonished someone had to go “clear to Africa” to equip the governor’s office. Chandler promised that he would panel the governor’s office with fine native woods from Kentucky’s backwoods.

Despite the best efforts of the Clements machine, A. B. Chandler prevailed in the Democratic primary, beating Bert Combs by about eighteen thousand votes. The Republican candidate in the general election, Edwin Denney, proved to be no match for Happy Chandler. Once again, Happy won the general election by the biggest majority given to a candidate in the state’s history up until that time.

Governor Chandler’s second administration was far less successful than his first. The Democrats were seriously divided by party strife; some remained loyal to the governor, while others owed their allegiance to Senator Earle Clements. Chandler found to his dismay it was exceedingly difficult to balance the state budget and keep his own campaign promises.

Happy’s second term was looking less than happy.