By Joe Rector

HBO aired a documentary about Robin Williams last week. Anyone who knows me well can quickly assure folks that I watched it. Since the beginning of his career, I followed him and lauded his creative and comedic abilities.

Williams hooked me with the first episode of “Mork and Mindy.” I’d never seen anyone who could fly through jokes, change personalities, and keep his audience laughing hysterically. The Orkian handshake and catchphrase “Nanu-Nanu” spread throughout the nation’s population. I remember using both during my teaching days at the time. Some students thought I’d lost my mind, but others who’d viewed the show smiled politely or laughed aloud as they recalled a skit from the show.

Other comedians became favorites of mine over the years. Tim Allen and his shtick had me rolling in the floor with laughter. I loved the way he grunted like a pig in his imitations of men. The irreverent comedy of the Punk Magician shocked everyone, but his warped sense of humor kept viewers laughing. Lewis Grizzard transformed his newspaper columns and books into stand-up acts that sold out as soon as they were announced. Yes, I was a fan of Bill Cosby and his “Cosby Himself” routine. His spot-on comments on parenthood had those of us with little ones realizing that we were normal.

Still, Robin Williams remained my comedy hero. When his “Live at the Met” video came out, I watched it and copied it to watch time and time again. Sure, Robin Williams was sometimes vulgar; at other times, he was crude; and on occasion, he bordered on disgusting. Even so, I always understood where he was going, which might say volumes about my own moral compass, but more than likely, it says that I could see that his intent was the humor, not the offense. In it all, he managed to keep fans laughing during his 2-hour long concerts.

I always wanted to see Williams, and in 2002 he scheduled a concert in Nashville. My older brother Dallas called and asked if I would like to see the show. I responded “yes” but that I couldn’t afford the ticket. He told me to be in Nashville the weekend of the event and that he’d get two tickets for us.

I made the trip on that weekend and spent some of Friday night sitting with Dallas on his screened porch. We talked for a bit about the concert, but then he uncharacteristically said he was going to bed. The next day he didn’t feel much better; his head was spinning, and he felt nauseated. The show was on Sunday evening, and Dallas rose that morning but didn’t stay up long. He stayed in bed all day, and when he was up for any reason, he apologized for not keeping me company. Closer to the concert time, he told me that he just didn’t feel well enough to go. I told him that was okay and that I could go by myself.

I saw my long-time favorite celebrity that August night, and he left the crowd at the grand Ole Opry House screaming for more, I saved the ticket stub and put it in a frame. It was a wonderful night.

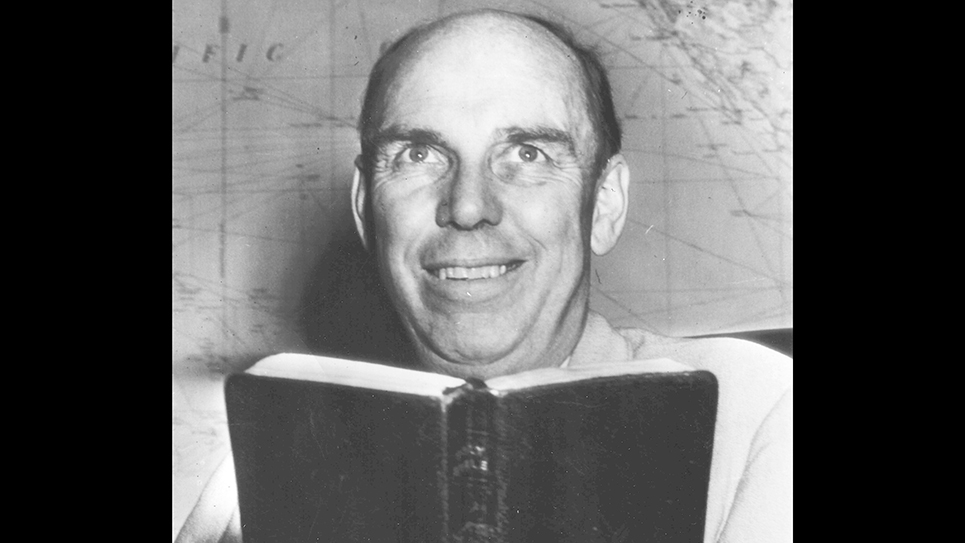

That weekend also turned out to be the first inkling that my brother was seriously ill. On Labor Day, his wife Brenda called to tell me he was in the hospital. Dallas had developed lung cancer that had metastasized to his brain. By January 2003, he was gone. I placed a photo of the Dallas in the frame that held the ticket stub to remember the entire circle of events.

I miss Dallas and thought about the concert and his illness as I watched the Williams’ documentary. My heart broke when I learned the comedian had committed suicide. The one hope I have is that these two men have had the chance to meet in heaven so that my brother can laugh as I did all those years ago.