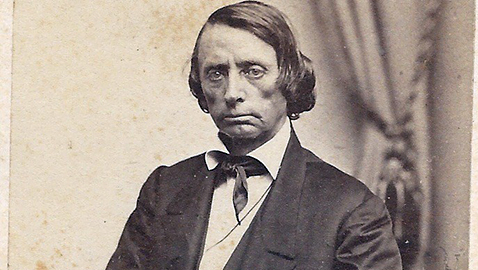

William Gannaway “Parson” Brownlow had been elected governor of Tennessee in 1865, taking the oath of office four days before General Robert E. Lee tendered his surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. Governor Brownlow was engaged in a heated reelection campaign against former congressman Emerson Etheridge. The Parson had pledged vengeance against the rebels and Brownlow had kept his word. The governor was a genuinely austere man, bragging he had never tasted liquor, save for medicinal purposes, disdained playing cards, refused to attend the theatre, and “never courted any woman except his wife.”

Brownlow sought a second two-year term as governor in 1867 and faced serious opposition in the person of Emerson Etheridge. A powerful and gifted speaker, Etheridge, like Brownlow, had been an adamant critic of secession and had also been a member of Congress from West Tennessee. Etheridge had become an outspoken critic of Governor Brownlow and the 1867 gubernatorial campaign quickly became heated and violent. Brownlow had allied himself with the Radical Republicans opposed to President Andrew Johnson. Emerson Etheridge was a conservative Republican who believed Johnson’s policies would help Tennessee to return to its pre-Civil War status. The legislature had given Governor Brownlow an almost insurmountable electoral advantage inasmuch as the election machinery in the state was almost entirely in the Parson’s hands. Brownlow denounced Etheridge in his newspaper with his own lively brand of invective, describing his opponent as little more than a “party scullion.” Brownlow derided Etheridge as “the Thersites of the stump” and accused his opponent of being “the trafficker of the most foul, vulgar and filthy slang ever spewed by an obscene mind upon the hustings.” Etheridge was well able to defend himself and cried the Brownlow administration was nothing more than an “ignorant, brutal and irresponsible despotism.” Etheridge claimed his election would end the “meanest tyranny which was ever hatched in the foul air of distempered times.” Brownlow was ailing and was unable to campaign on his own behalf, having to rely upon surrogates to speak for him. Congressman William B. Stokes met Emerson Etheridge in debate where they excoriated one another. Etheridge finally sniffed, “Mr. Stokes says he is not educated. He need not have told it.”

The Parson was ailing during his reelection campaign and was not able to speak on his own behalf, while Etheridge was one of the most gifted public speakers in Tennessee at the time. Brownlow used surrogates to speak, urging his reelection. Governor Brownlow was not afraid of controversy; in fact, he regularly courted it. Brownlow had infuriated former Confederates by insisting former slaves be given the right to vote. It was Brownlow’s opinion “a loyal Negro was more deserving than a disloyal white man.” Nor was Brownlow loath to use any means necessary to accomplish his goals. When he sought to have the state legislature ratify the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, a small minority of legislators loyal to President Andrew Johnson, who opposed the amendment, tried to leave the Capitol. Brownlow had the Sergeant-At-Arms arrest at least two recalcitrant legislators who sulked in a committee room. The legislature voted 43 – 11 to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, but one of the legislators who had been arrested refused to sign the document and resigned his office in protest. It merely delayed the ratification briefly, as his successor was happy to sign the ratifying document. Governor Brownlow gleefully sent along Tennessee’s ratification to the Fourteenth Amendment, along with a gloating note to President Andrew Johnson, stating, “My compliments to the dead dog in the White House.”

While Emerson Etheridge campaigned gamely, he surely realized there was little hope of victory. Both Etheridge and Brownlow were Republicans, albeit from very different factions of the party. With former Confederates unable to vote, Brownlow assured his reelection to a second term as governor by organizing a state guard. The governor appointed General Joseph A. Cooper to head the guard, which was ostensibly charged with “protecting” the voters. In reality, the guard did little more than antagonize and intimidate the opposition. Brownlow won a sweeping reelection, winning 74,848 – 22,548 for Etheridge.

William G. Brownlow was never ashamed of his methods. He ruled Tennessee as he had once debated a fellow clergyman, the hapless Adam Pryne in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Brownlow snapped at the Reverend Pryne, declaring him to be “an unwashed, unmitigated, unregenerate and God-forsaken abolitionist who, if you will dare show yourself South and repeat your wholesale abuse of slaveholders and your vile reflections upon the virtue of Southern ladies, shall be treated to a coat of tar and feathers and rode out of town on a rail by free Negroes and Northern prostitutes who are filling our towns.”

Governor Brownlow, especially hated by former Confederates, began receiving serious threats against his life. Congressman Samuel Arnell, the beneficiary of Brownlow having thrown out several hundred votes inside Arnell’s Fourth District, had quite nearly been assassinated. Violence was increasing in Tennessee through the auspices of the Ku Klux Klan, headed by former Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Members of the Klan were no less shy in hiding their motives than was Governor Brownlow. The Grand Cyclops of the Tennessee Ku Klux Klan sent a threatening letter to the governor. General Forrest left little to the imagination when he stated in a newspaper interview he did not for a moment believe that Brownlow’s government had “any legal existence.” General Forrest warned if the Brownlow administration committed any overt “outrages”, the governor and his cronies would “be swept out of office existence and not a Radical will be left alive.” Forrest later joined several other signatories in petitioning the governor. The General and his friends promised to cease their activities if Brownlow would agree to restore the right to vote to former Confederates. Governor Brownlow refused to consider the idea and instead insisted the legislature give him more enforcement powers and set about reconstituting his state guard. The legislature promptly gave the governor new powers enabling him to throw out voter registrations in Tennessee. Brownlow also demanded federal troops be sent to Tennessee to station at the polls in twenty-one counties. Brownlow’s new powers came in handy as he was supporting General Ulysses S. Grant for president in 1868. Nor was the governor afraid to use them. Brownlow purged the entire voter registration roll in Lincoln County. Congressmen William J. Smith and Lewis Tillman, both Radical Republicans, had been defeated in the election. The congressmen believed Klan members had intimidated and threatened enough voters to cause their defeat. Governor Brownlow agreed and threw out enough ballots from Coffee, Marshall, Fayette and Tipton counties to elect Smith and Tillman.

The fiery Parson did not seek a third two-year term as governor in 1869, but rather had his eye on the U. S. Senate seat held by David T. Patterson, who was also Andrew Johnson’s son-in-law. Brownlow wanted to go to Washington to aid the Grant administration and the legislature easily elected the governor over the opposition of Congressman William B. Stokes, 63 – 39. Before leaving for Washington, Brownlow sold the Knoxville Whig. Brownlow departed Nashville for the nation’s Capitol, leaving behind his record as governor and there are many who believe William Gannaway Brownlow was Tennessee’s worst chief executive.

Brownlow was not one to doubt himself. The Parson once made the statement, “If I had been allowed to hunt up about 200 anti-slavery agitators in the North…if I had taken these Northern fanatics and an equal number of our Southern, God-forsaken, hell-deserving secessionists and dis-unionists…I would have erected a common gallows and we would have none of the troubles which afflict the country today.”

Despite his election to the United States Senate, Brownlow’s health had not improved; in fact, it was rapidly deteriorating. Brownlow was unable to give speeches on the Senate floor, necessitating his comments to be read by the Clerk of the Senate. Brownlow was a strong supporter of the Enforcement Act of 1870, which was designed to give the president greater authority to enforcement the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution. More specifically, it was drafted to keep organizations like the Ku Klux Klan from threatening the voting rights of former slaves and free blacks. The bill outlawed any attempt by state officials to discriminate against any person on the basis of race or color. The bill also gave federal courts the ability to enforce the legislation. President Grant was empowered to use the federal army to uphold and enforce the terms of the legislation, as well as allow federal marshals to file charges against those who would commit election fraud, attempt to bribe or otherwise intimidate voters. The bill did not go far enough to suit Senator Brownlow, or for that matter, many of the Parson’s colleagues in Congress. The Congress approved the Second Enforcement Act of 1871, which gave President U. S. Grant the right to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in the government’s efforts to curtail and destroy the Ku Klux Klan and other organizations like it. Brownlow was an enthusiastic supporter of the second enforcement act.

Senator Brownlow could not have been especially pleased by the political turn in Tennessee. Much of what the Parson had done as governor was steadily being undone by his successors. Tennessee was drifting back toward the Democratic Party, while the Republicans were slowly relinquishing their hold on the Volunteer State. Weak and ill, William G. Brownlow could accomplish little as a member of the United States Senate. With the state government under the control of the Democrats, Brownlow knew he could not be reelected to a second term in the Senate. Perhaps Brownlow did not wish to be reelected to the Senate as his health was worsening and he was getting old. For once in his life, William G. Brownlow left quietly. Departing Washington, D. C., Parson Brownlow returned to his home in Knoxville. Clearly, Brownlow did not intend to be idle or simply retire. The former senator bought an interest in the Knoxville Chronicle. The Chronicle was published by William Rule; a friend of Brownlow’s and the elder man had been a mentor to the younger publisher. Rule obligingly changed the name of the newspaper to the Knoxville Whig and Chronicle.

Brownlow remained a highly controversial figure into his dotage. Once while seriously ill, the Parson had been visited by a fellow minister, who wondered about Brownlow’s prospects for the afterlife. “If the books have been properly kept,” the Parson replied, “I believe they will find a small balance in my favor.”

Although ill since returning to Knoxville, William G. Brownlow had taken more interest in events shortly before his unexpected death. The Parson had employed workmen to repair the porches of his home on Cumberland Street. Brownlow paid the workmen after personally supervising the work on his porches and fences. The Parson went to bed at his usual time, but sometime in the night he was stricken and a physician was called. Apparently the former senator was important enough to merit two doctors and D. T. Boynton and James Rodgers answered the call. Contrary to the end, Brownlow refused to take any stimulants, causing his family to despair and realize the Parson was finally coming to the end of his life. William G. Brownlow’s passing away, according to his family which surrounded him during his final hours, was far more peaceful than his life had been.

“He was true to his friends and relentless toward his enemies,” the Memphis Evening Ledger eulogized the Parson. “He could express more vituperativeness and scorching hate than any half dozen men that ever appeared in American politics. His style has been imitated, but never successfully copied by men of less native intellect and courage.” The Evening Ledger concluded William G. Brownlow was “a strange compound” of a person, but sighed, “Whatever his faults and the warp of his nature, he was honest, fearless and consistent in his way.” So he was.