Senator Albert Gore was campaigning hard for a fourth term in 1970. Gore had fended off a determined challenge in the Democratic primary from Governor Buford Ellington’s former press secretary, Hudley Crockett. Senator Gore’s opposition to the administration of Republican President Richard Nixon had made him a target in the 1970 elections and his opponent, GOP Congressman Bill Brock, was well financed and shrewdly using many of the same issues hurled by Hudley Crockett.

Albert Gore was seen by many Tennesseans as out of touch, too liberal, and aristocratically arrogant. Gore had first been elected to the United States Senate in 1952 by defeating Senator Kenneth D. McKellar, a veteran of thirty-six years. The frail, often ill and aging McKellar had been retired to make way for the relatively youthful and vigorous Albert Gore, who had been almost forty years younger than McKellar.

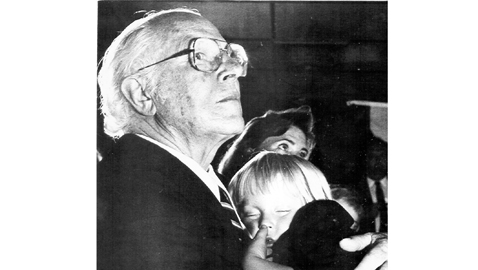

Gore was sixty-two years old in 1970 and much like his political idol Cordell Hull, he had a stately appearance. His white hair and political cunning caused him to be referred to as Tennessee’s “old gray fox,” a title Albert Gore proudly accepted.

As Gore faced perhaps the toughest campaign of his career, it was obvious Tennessee’s politics had changed dramatically. The 1970 election would prove that Tennessee had finally evolved into a genuine two-party state. Most of Gore’s contemporaries were either dead or retired; Governor Frank Clement had lost a 1966 Senate race to Republican Howard Baker and had died in a car crash in 1969. Senator Este Kefauver had died from a ruptured aorta while awaiting surgery in 1963. Senator Ross Bass had lost the 1966 senatorial primary to Governor Clement and was working as a lobbyist, while Governor Buford Ellington was headed toward retirement following the 1970 election.

Neither Democratic gubernatorial nominee John Jay Hooker nor Senator Gore received help from Governor Ellington, who was the acknowledged leader of conservative Democrats in Tennessee. Ellington had been challenged in the 1966 primary by Hooker and the governor liked Hooker no better in 1970 than he had in 1966. Ellington had received encouragement to run against Gore himself in 1970, but chose to support the candidacy of Hudley Crockett instead. As Hooker reeled from the collapse of the Minnie Pearl fried chicken franchise and Gore tried to fend off Bill Brock, Buford Ellington maintain something of a golden silence.

While Gore fought back, in the end he was swallowed by the rising tide of the times. Bill Brock carried Tennessee, while Gore’s native Middle Tennessee provided him about an equal margin. The contest was decided by the election returns from West Tennessee and the lingering ill will there towards Senator Gore helped Bill Brock win. Brock won with 52% of the vote and it was the end of Albert Gore’s political career.

Albert Gore made an eloquent speech conceding his loss and had to contemplate carving out a new life for himself outside of Congress where he had served continually since 1939. Gore wrote a book, taught occasionally at Vanderbilt and tried to practice law. Senator Gore had never really practiced law and it was not successful. His salvation appeared in the form of millionaire industrialist Armand Hammer, who selected Albert Gore to serve as the Chairman of the Island Creek Coal Company.

Hammer had been Gore’s business partner in an enterprise selling cattle on the former senator’s Carthage, Tennessee farm. Gore’s affiliation with the Island Creek Coal Company provided him with an excellent income and he became an elder statesman of the Democratic Party. He did not have to wait long for the political ascension of his son and namesake, Albert Gore, Jr.

Al Gore won a heated primary to win the Congressional seat of the retiring Joe L. Evins in 1976. Naturally, the former senator was delighted by his son’s success. Al would be reelected until 1984 when he ran for the United States Senate seat being vacated by Howard Baker. Congressman Gore faced future Knoxville Mayor Victor Ashe, who was then a member of the Tennessee State Senate. Albert Gore, Jr. won that contest easily and was a presidential candidate in 1988.

Albert Gore, Jr. made his first run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1988 and lost, but he accomplished something his father never did.

Tennessee’s Old Gray Fox, despite his years, seemed invigorated by his son’s presidential bid. The former senator was always very careful to do nothing that might inflict an injury on his namesake’s political career, but he was an effective surrogate on his son’s behalf.

Albert Gore, Sr. not only lived to see his son chosen by Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton to run as the vice presidential candidate for the Democratic Party in 1992, but to win. The elder Gore had long harbored national aspirations and his son had succeeded where he had failed.

Senator Albert Gore had been somewhat wounded when his son had first run for Congress and had not wanted his father openly campaigning for him. When he was elected to the United States Senate in 1984, Albert Gore, Jr. once again wanted his father kept behind the scenes. When the younger man sought the Democratic nomination for president, both of Albert Gore, Jr.’s parents campaigned hard for him.

In fact, Senator Gore had pushed young Al to make the race, believing he could win. The old gray fox campaigned hard, especially in Iowa. Although 79 years old, Albert Gore seemed to have endless energy in promoting his son’s candidacy. The southern strategy employed by the Gore campaign worked reasonably well, but the candidacy of Jesse Jackson undermined Al Gore’s effort in the South.

Al Gore had no trouble being reelected to the United States Senate in 1990, but another presidential run in 1992 was not to be, as the Gore family had to endure a near tragedy when Albert Gore III was hit by an automobile. Still, Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton selected Senator Albert Gore, Jr. as his running mate.

The success of the Clinton – Gore ticket thrilled no one more than Albert Gore, Sr. The former senator reveled in the success of his son. Gore spent considerable time on the family farm in Carthage, Tennessee and opened a large antique mall, which featured one of the automobiles owned by the Gore family in the 1950s. Senator Gore was still highly visible at many public events and parsed out a few public interviews, but the old gray fox was still careful, protective of his son’s career, which was his legacy.

Having reputedly earned some $500,000 a year from his job working for industrialist Armand Hammer, Albert Gore was quite comfortable financially. He and his wife Pauline set out to enjoy life in their twilight years.

Both Senator and Mrs. Gore were devastated by the loss of their only daughter, Nancy, when she died in 1984 of lung cancer. Albert Gore, Jr. was also deeply affected by the passing of his beloved older sister. It was a blow from which none of the Gores ever quite completely recovered.

Albert Gore, Sr. died of natural causes at his home in Carthage on December 5, 1998, just a few days short of his 91st birthday. The former senator was surrounded by family members as he slipped away peacefully. He and Pauline Gore had been married for 61 years.

With the passing of Albert Gore., the tributes to the former senator came pouring in; the obituaries related the substance of Gore’s life and his Congressional career. Theirs had truly been a marriage that was both loving and the two complimented one another. One Gore supporter recalled that Gore was quite “politically perceptive”, yet described Pauline Gore as even more so. The Gores had been amongst the first to recognize an unknown twenty-nine year old candidate in Delaware could upset a veteran senator and one of the most popular political figures in the state in 1972. Albert and Pauline Gore were responsible for raising nearly one third of all the money Joe Biden raised that year to get elected to the United States Senate.

Remembered for his oratory, Russell Baker said Albert Gore’s voice was accented by the “piney-woods Southern rather than magnolia Dixie”. Former Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield of Montana noted, “Albert ran his boats along the lines his conscience dictated. It took a lot of guts. He had them, but he paid for it.”

President Bill Clinton eulogized Gore as “the embodiment of everything public service ought to be.” Clinton said Gore “was a teacher, he was a progressive, he helped to connect the South with the rest of America.”

Clinton also mused that Albert Gore could have gone farther in politics than he did, saying, “You know, he might have been himself in national office if he hadn’t been just a little too far ahead of his time.”

Pauline Gore, unquestionably the driving force behind her husband for most of their life together, died six years after the former senator at age 92. Today they sleep together, side by side, as they were for most of their lives on earth.

Stories in this Week's Focus

- The Knoxville Focus for July 7, 2025

- Publisher’s Positions

- Famous Grainger Co. Tomato Festival coming soon

- Augustus O. Stanley of Kentucky

- ETHC celebrates Sam Dow, the Founding Father of Knoxville baseball

- CAK’s Speck watched his boys learn how to surf

- The Knoxville Focus for June 30, 2025

- Vote no to city tax increase in November

- Seymour girls lacrosse team has magical 2025, makes state championship match

- The Gentleman From Kentucky: J. C. W. Beckham