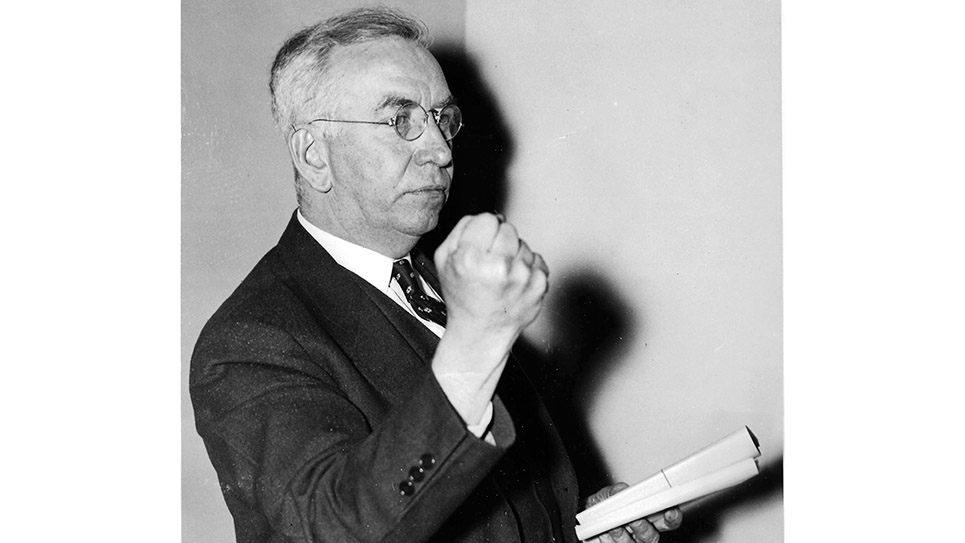

Kenneth D. McKellar walking near the Capitol just after his election to the U. S. Senate, 1917. Photo from the author’s personal collection. Kenneth D. McKellar walking near the Capitol just after his election to the U. S. Senate, 1917. Photo from the author’s personal collection.

Kenneth McKellar was forty-two years old when first elected to the House of Representatives in a 1911 special election to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Congressman George Washington Gordon. His rise to political prominence had come despite the fact he was not a native of Memphis or Tennessee, having been born in Dallas County, Alabama in 1869. In fact, when Kenneth McKellar was born, Ulysses S. Grant had not yet taken the oath of office as President of the United States. When McKellar left Congress in 1953, another famous general, Dwight D. Eisenhower, was about to assume the presidency.

Like many Southern families just after the Civil War, finances had been precarious in the McKellar household. The future senator’s father apparently suffered from some sort of debilitating illness and the McKellar brothers had to work very hard to make ends meet. Kenneth McKellar, with the help of his older brothers, managed to attend the University of Alabama where he roomed with John Hollis Bankhead, II, son of Alabama’s United States Senator and a future member of the Senate himself. McKellar earned Bachelor’s, Master’s and LL.B. degrees from the University of Alabama and for much of the rest of his life wore his Phi Beta Kappa key on a watch chain that usually hung across his vest.

K. D. McKellar arrived in Memphis with his new law degree, exactly fifteen cents in his pocket, $600 in debt to his older brothers, and wearing a suit that had seen far better days. McKellar thought he was only visiting Memphis when he got off the train, intending to spend some time with his brothers before heading to California where he anticipated opening a law office. His older brother Robert, a successful executive with one of the railroads, convinced McKellar to remain in Memphis for a while and if he chose to continue his journey on to California, Robert promised to get him a train pass.

McKellar soon found he enjoyed Memphis and liked the social life where his relatives were well established in the community. The young attorney accepted an offer to join the law firm of Metcalfe and Walker. It was not long before McKellar began his first flirtation with politics, serving as an elector for the Democratic presidential ticket headed by William Jennings Bryan, then known as the “Boy Orator of the Platte”, in 1896. McKellar had left the Metcalfe firm the year before to form a partnership with Colonel William Carroll and James Chalmers. The firm of Carroll, Chalmers and McKellar was prosperous and after Chalmers died in 1898, the firm was known as Carroll and McKellar.

Colonel Carroll was a highly esteemed member of the Bar and quite well connected, both socially and politically. Colonel Carroll was also the father of a very beautiful daughter with whom McKellar was said to have fallen in love. Evidently McKellar put off asking the young lady to marry him and made the mistake of taking a long holiday and was heartbroken to discover upon his return the object of his affections had married another man. It was a blow from which the extraordinarily sensitive McKellar never recovered and he never married, remaining a bachelor for the rest of his life.

While McKellar described himself modestly as “a plain lawyer” to friends, he became a very successful one. After practicing law for almost twenty years, McKellar had earned something like $300,000, the equivalent of quite nearly $7,000,000 today. Despite his success as an attorney, McKellar found the time to become involved in civic affairs and politics. McKellar was a member of the Jackson Club, which was an organization dedicated to reforming local government. McKellar authored a program to do precisely that and a new city charter was amended in 1905. It was around this time McKellar became better acquainted with another transplant to Memphis, Edward Hull Crump. Crump had come from Mississippi and the association between the two men would grow closer as the years passed and would continue for almost fifty years.

McKellar was politically prominent enough by 1910 to be urged to run for governor by many Democrats. While McKellar appreciated the compliment, he realized the bitter division inside the state Democratic Party would make it very difficult for any Democrat to win. McKellar thanked his admirers, but refused to run, seemingly content to practice law. McKellar did campaign for the eventual Democratic nominee for governor, U. S. Senator Robert Love Taylor. Bob Taylor was one of the most famous Democrats in Tennessee, much loved by many thousands of Tennesseans and had already been elected governor three times previously, once defeating his own brother Alf, who was a Republican, in a contest that was known as the “War of the Roses.” Taylor, too, was uneasy by the fractured state of Tennessee’s Democratic Party and was quite happy in the Senate. McKellar’s premonition had been correct and Taylor lost to a little known Republican from Newport, Tennessee, Ben W. Hooper.

When the Tennessee General Assembly convened in 1911, McKellar’s name was presented as a candidate to succeed U. S. Senator James B. Frazier. Senator Frazier wanted a second term, but soon discovered he could not muster the necessary votes to be reelected. It was a “fusionist” group of Independent Democrats and Republicans who chose the next senator, Luke Lea of Nashville.

K. D. McKellar was vacationing when the Congressman from Memphis, George Washington Gordon, died suddenly on August 9, 1911.

Gordon had not only been a general in the Confederate Army, but had been one of the first members of the original Ku Klux Klan. When the seventy-four year old Congressman Gordon went on to meet his Maker, the leading candidate to fill the old general’s seat was the evidently aptly named Tom Looney. One of McKellar’s brother’s wired him while he was on vacation, informing him of Congressman Gordon’s death and the groundswell of support for his candidacy of he would run for Congress. McKellar wired back a terse telegram: “Not interested.”

When supporters of a prospective McKellar candidacy sadly reported the attorney had no interest in running in the special election, Looney promptly bragged McKellar did not want to run because he could not win. Possessing a very quick temper, McKellar immediately wired one of his brothers to announce his own candidacy for Congress and instructions to pay the filing fee. McKellar cut short his vacation and returned to Memphis to begin his campaign to represent Shelby, Fayette, Hardeman and Tipton Counties in the House of Representatives.

McKellar easily defeated the boastful Tom Looney and assumed his seat in Congress. Upon his arrival in Washington, D. C., McKellar confessed he found it “very pleasant” and concluded “it looks like I shall like it very much.” McKellar believed the success of a freshman member of Congress was largely dependent upon interpersonal relationships and he set out to try and meet the other members. McKellar also applied himself to learning the rules of parliamentary procedure, which he soon mastered.

McKellar found himself swamped with work; a heavy load of correspondence from constituents besieged him daily and the new Congressman confessed he was surprised by the number of entreaties from constituents asking him to sponsor private bills for them. At that time, there was no Social Security and any pension for veterans or the disabled or gravely ill required a private act for the specific benefit of the petitioner.

K. D. McKellar was also concerned about roads. When he was first elected to Congress, he had thought to drive his new Packard automobile from Memphis to Washington, D. C. McKellar had been shocked and indignant to discover once he was outside Memphis, the roads were barely passable. After several minor accidents and numerous flat tires, a very frustrated and angry McKellar decided to ship the expensive Packard by rail. It was an experience he did not forget and by December of 1911, McKellar was telling friends he had determined to make a fight for a system of Federal highways.

McKellar’s fight for a Federal highway system went on for several years. It was not until 1916 that Congress finally approved a Federal Aid Road Act. There was considerable opposition throughout the entire government to spending so much money on roads and President Woodrow Wilson himself was dubious about excessive expenditures for Federal highways. Congressman McKellar and Alabama Senator John H. Bankhead called on President Wilson at the White House to urge Wilson to support the highway bill. The President promptly informed McKellar and Senator Bankhead he did not believe spending Federal money on highways to be constitutional.

Bankhead watched in horrified silence as McKellar told the President any money spent on developing a national highway system could easily be justified as being necessary for the defense of the United States, which certainly was constitutional.

McKellar reminded the President Wilson of a well-publicized event where a German submarine had docked in an American harbor so the Captain and crew could go into town for lunch. The implication was not lost on Wilson, who then asked just how much money would be needed to start a Federal highway network. Senator Bankhead had been willing to agree to $40,000,000 to start, but Congressman McKellar told the President he thought $75,000,000 would likely get the program underway, which would surely help create an expanded network of highways that would facilitate more rapid movement of both troops and material.

Senator Bankhead was aghast at the enormous sum suggested by Congressman McKellar. Senator Bankhead was even more astonished when President Wilson readily agreed to the much higher figure and the bill passed by the Congress included the $75,000,000 to be spent over a span of five years. As the two men left the White House, Bankhead turned to McKellar and told the younger man he was certain he had killed the project when he asked for the stars and the moon.

Closer to home, McKellar waged a lengthy battle to acquire a second bridge spanning the mighty Mississippi river from Memphis to Arkansas. It was a hard fought battle and there were more than a few times when it appeared all was lost, but McKellar skillfully negotiated not only the tedious legislative process, but also fought off a railroad that wanted to maintain its own monopoly. McKellar got yet a different railroad to agree to pay for much of the construction of the new bridge and fought off crippling amendments to the bridge bill by the leader of his own party in the House of Representatives. It was an impressive performance, especially by a freshman legislator and McKellar’s constituents were impressed.