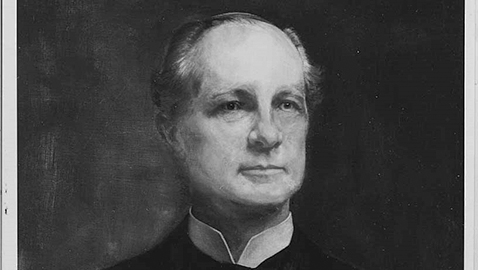

James Beriah Frazier had been elected governor of Tennessee in 1902. A tall, stately man with an elegant appearance, James B. Frazier certainly looked the part of a governor. Despite his aristocratic appearance, James B. Frazier had worked his way through law school. The future governor taught school for two years and read the law in his spare time. Frazier was admitted to the Bar in 1880 and began the practice of law in Chattanooga. Both of Frazier’s grandfathers had fought in the Revolutionary War. One of his grandfathers, Abner Frazier was “so young at the time that he received both praise for his courage and a whipping for running away from home to join the army.”

Politics had not always been James B. Frazier’s natural calling; indeed, his first statewide campaign was when he ran as a presidential elector for William Jennings Bryan in 1900. Frazier, as was true with many lawyers of the time, proved to be quite an orator. Along with his ability to sway juries, his appearance certainly didn’t hurt. Two years later, Frazier emerged from the Democratic state convention as the Democratic Party’s nominee for governor. James B. Frazier proved to be a popular choice and for once, Tennessee Democrats seemed perfectly united as the general election approached. As Frazier campaigned across the state, reporters filing their dispatches noted the “magnetism” of the candidate. John Leiper, a correspondent for the Nashville Tennessean covering the Frazier campaign, noted an appearance by the candidate in Obion County. Leiper wrote Frazier “completely won his audience” in the course of his speech. Interestingly, Leiper also commented, “Wheat sowing prevented many farmers from being present at the speaking.”

A similar report filed by Leiper from a campaign stop in Dresden, Tennessee where both Frazier and his Republican opponent, Judge Henry Tyler Campbell, faced off before a large audience. Campbell was thought to be a powerful orator, but the Tennessean correspondent gleefully noted Frazier won cheers from the audience as he “hurled the most withering replies to many vulnerable points in Judge Campbell’s argument.” Following the mini-debate, Frazier was thronged by much of the audience, who congratulated him. John Leiper did not fail to observe the frosty reception Frazier received from partisan Republicans, but was quick to point out the GOP members of the audience “showed the appearance of a badly beaten crowd long before Mr. Frazier had concluded” his speech. Although the Tennessean was an unapologetic Democratic paper, John Leiper may well not have exaggerated James B. Frazier’s appeal to the people of Tennessee. Frazier won the governorship by the largest margin ever accorded a candidate until that time.

Governor Frazier sought a second two-year term in 1904 and once again was nominated unanimously by the Democratic State Convention. Tennessee Democrats also adopted a party platform, which included denouncing the “appalling increase in the expenditures of the Federal government under the Republican party” which “demonstrates the necessity of a return of the Democratic party to power as the only means of bringing a wise economy in administering the affairs of the government.” The Tennessee Democratic State Convention also condemned President Theodore Roosevelt who “by his official action, has wantonly precipitated the race issue in a manner involving as a logical and necessary sequence social equality between the white and colored people of this country, and deserves, in consequence thereof, the condemnation of all right-thinking-people.”

The governor had not lost his touch with Tennesseans, as he made a stop in Clarksville, Tennessee as the general election came to a close. Arriving from Nashville on a train, Governor Frazier went to the Arlington Hotel where he remained until going to the courthouse. Frazier spoke to an overflow crowd in the Circuit Courtroom. A reporter wrote, “His speech was one of the best delivered here in years.” In Springfield, Tennessee hundreds of people turned out in mid-day to greet the governor at the Commercial Hotel and the entire town was bedecked with bunting and flags. Frazier did not disappoint his audience. Speaking at the Tabernacle to a crowd of one thousand people, Governor Frazier “spoke in a most forceful, earnest and convincing manner, delivering one of the most masterful efforts ever heard here.” A Tennessean reporter wrote the governor was frequently interrupted by applause “throughout and in parts of his speech his audience alternated with laughter and tears.” When presented with a bouquet of beautiful flowers, the governor told a tale on himself. Frazier said while campaigning in a small East Tennessee town, he had been gifted with another bouquet and although quite beautiful, the flowers paled in comparison with the lovely young creature who presented them to him. Overcome, the governor confessed he had bestowed an “old fashioned Democratic kiss” on the young lady. Evidently, Mrs. Frazier was none too pleased and he said he was taking the bouquet given to him on this occasion home as a peace offering. Once again, James B. Frazier won a thumping victory in the general election, defeating Jesse M. Littleton. Frazier won the greatest majority ever given a Democratic candidate for governor in a presidential election year.

Governor Frazier was just a couple of months into his second term when U. S. Senator William B. Bate died unexpectedly in Washington, D. C. A former governor and Confederate general, Bate had caught a chill at the inauguration of President Theodore Roosevelt, which developed into pneumonia. The seventy-eight year old senator had just been reelected to a fourth six-year term. The legislature would elect a new senator to serve what was essentially a full term. Two former Tennessee governors, Robert Love Taylor and Benton McMillin, had long harbored ambitions to serve in the United States Senate. Both immediately began to marshal campaigns, but Governor Frazier was interested in going to the Senate. Speaker of the State Senate, John I. Cox, would succeed Frazier as governor in the event the chief executive was elevated to the U. S. Senate. Although both Taylor and McMillin were enormously popular with their fellow Democrats, it was readily apparent Governor J. B. Frazier was the likely choice of the legislators. Indeed, Frazier appeared so strong that some friends and long-time supporters of McMillin and Taylor advised them to withdraw from the Senate contest. The Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle ran a story stating “personal and political friends of former Gov. McMillin openly stated on Thursday night that they would advise him to keep out of the race.”

The Democratic Caucus in the General Assembly quickly settled on James B. Frazier as its nominee. When Representative Gordon placed Governor Frazier’s name in nomination, he bellowed, “I will place in nomination before this caucus that tall Tecumseh of the Tennessee, the Democratic rock of Chickamaugua, that splendid orator, Governor and statesman, James B. Frazier…” One supporter of Robert L. Taylor, Senator McLaurine, claimed Representative Gordon had “laid the dagger to the heart” of the former governor. McLaurine withdrew Taylor’s name from consideration by the Democratic Caucus. “If you propose to close your eyes to the voice of the people and if you propose to be a hostile court and judge him now he will make no defense,” McLaurine cried, “but we will sit quietly by and see this conspiracy through.” Senator McLaurine then thundered a warning to his colleagues: “But I tell you there is another day coming. I tell you there are men in this Assembly who had joined in this conspiracy who, when they go home and face their people, will feel like going to the place where the worm dieth not.”

James B. Frazier was easily elected to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Senator William B. Bate. Frazier was the last governor of Tennessee to be elected to the United States Senate by the General Assembly. Speaking before the legislature, Frazier was careful to say, “If I did not believe that my mantle would fall upon worthy shoulders and that I would be succeeded in the office of Governor by a man who will do his whole duty, I would refuse this nomination. In proper time my mantle will fall upon a man who is worthy of it, therefore I accept the honor at your hands.”

In five short years, James B. Frazier had gone from practicing attorney to governor and United States senator. Still, despite Frazier’s high personal popularity, his election to the Senate had generated some bitterness, especially with the legislature having ignored two of the most prominent Democrats in the state. The Jackson Sun wistfully commented its only objection was “that a good Governor was spoiled in making a Senator.”

The way James B. Frazier was elected to the United States Senate, elbowing both former governors Robert L. Taylor and Benton McMillin out of the way, was noted in Tennessee’s newspapers. The Bristol Courier snapped, “The Tennessee Legislature resolves that United States Senators should be elected by the people, also that they are the people.” The Cookeville Press crowed Tennessee would be well represented in the U. S. Senate by having two “young giants” such as Edward W. Carmack and James B. Frazier in the upper house of Congress. The Tullahoma Guardian huffed, “The indecent haste of the Democrats of the ‘machine’ in the Legislature, in nominating a successor to the lamented Bate, is a matter which is calculated to bring the blush to the cheeks of every man and woman in Tennessee.” The Giles County Record agreed. “When these men (who voted for an early caucus) face an angered and an outraged constituency for re-election two years hence, they will find that the people can make and unmake ‘statesmen’, and there will be many empty cradles and many missing darlings when the roll call of the next Legislature comes.” The Newport Times thought Frazier’s election to the Senate was a wonderful thing. “Too much praise cannot be given James B. Frazier. Like the heights of Pisgah, he towers above them all. In the Senate of the United States, we predict he will leave his impress and stand with the highest. His rapid rise in politics is without an equal.”

The seed of discord had been sown by the method of James B. Frazier’s election and it would continue to fester for the remainder of his term of office. Many believed Senator E. W. Carmack had preferred Frazier as a colleague over either Robert L. Taylor or Benton McMillin. The legislators were sorely stung and the General Assembly agreed to be bound by the results of a special primary election in 1908. Senator Carmack had to defend his seat against former governor Robert L. Taylor and lost. When James B. Frazier’s term expired in 1911, he was quickly eliminated as a possibility for reelection, largely because of the “snap” caucus six years previously. Regular Democrats that year were unable to elect Benton McMillin to the U. S. Senate. McMillin faced the opposition of a combination of Republicans and Independent Democrats who elected thirty-year old Luke Lea to replace James B. Frazier in the Senate.

Frazier returned to his law practice and flirted with the idea of running for governor once again from time to time, but remained content to take his place as an elder statesman. James B. Frazier remained a highly sought-after and popular dinner speaker in Tennessee almost to the day of his death. Eventually, Frazier formed a law partnership with his son and namesake, James B. Frazier, Jr. The former governor lived to see his son become U. S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Tennessee under President Franklin Roosevelt. In 1937, James B. Frazier, eighty years old, was beginning to ail. He was sitting in the study of his home when he was felled by a heart attack.

To the very end, James B. Frazier remained a gracious and charming man, a gifted speaker and a true gentleman.