“A college boy cannot successfully go through life by graduating in football, baseball or highballs, for the responsibilities of life are not ball-bearing.” – William H. Murray

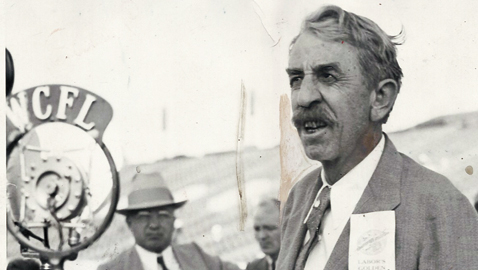

William H. Murray is almost invariably described as Oklahoma’s most colorful political figure. Considering he went out of office in 1935, that is saying something. Lean and lanky, rough hewn with a weathered face dominated by a drooping moustache, William Murray had been in and out of office for decades before reaching the pinnacle of his political success by being elected governor of Oklahoma in 1930. “Alfalfa Bill” received his nickname, which stuck to him even in death, for his fiery campaign speeches which usually contained some reference to the merits of growing alfalfa as a crop. Murray grew alfalfa himself and could rhapsodize about the crop at length. Murray was the friend of the farmer and the champion of the little man.

Born November 21, 1869, in Toadsuck (the town, thankfully, changed its name years later), Texas, William Henry Davis Murray taught school, as well as largely taught himself. Murray was also a prolific writer and a farmer. A self-educated lawyer at a time when one could “read” the law, he passed the examination and became a practicing lawyer. Yet in truth, Murray never really prospered in any of his chosen professions.

Financially and personally, Murray’s most significant affiliation was with Douglas H. Johnston, the governor of the Chickasaw Nation. Murray became legal counsel to the Chickasaw Nation through his friendship with Governor Johnston. Later, he married Johnston’s niece, Mary Alice Hearrell. Together, the Murrays produced five children.

Murray led a convention to propose statehood for the State of Sequoyah, which was to be composed of the Five Civilized Tribes living in the Indian Territory. President Theodore Roosevelt, leery of a state which would likely be dominated by the Democrats, refused to consider statehood for both the Indian and Oklahoma territories. Ultimately, statehood was granted to one new state, Oklahoma, and William H. Murray served as the first Speaker of the House of Representatives. Murray was also a racist who had appended several clauses to the state constitution and Theodore Roosevelt had refused to allow Oklahoma to become a state until those same clauses were stripped away. After that, Alfalfa Bill was not much enthused about any Roosevelt.

As Speaker, Alfalfa Bill tried to revive his Jim Crow laws. He was dissatisfied as a member of the Oklahoma House and quit after a single term. Murray had his sights set on bigger things and ran for governor in 1910, but lost. In 1912, he ran for an At-Large congressional seat and won. By 1914, the At-Large seat had been abolished and he ran for reelection from the Fourth District and was elected. Congressman Murray sought a third term in 1916, but lost inside the Democratic primary. Murray was on the campaign trail again in 1918, fervidly seeking the Democratic nomination for governor. Murray lost again.

Bill Murray returned to his home in Tishomingo, but his law practice did not flourish and his political disappointments left him unhappy. Thinking he might find a better life elsewhere, Murray led a group of Americans, including his own large family, to Bolivia, where he established an American colony in 1924. Life in the colony was almost unbearably hard and by 1929, Murray, his family and followers had returned to Oklahoma.

Once again, Bill Murray sniffed the political air and thought the time ripe for a comeback. He entered the Democratic primary for governor, facing at least four serious opponents. Among his opponents were a sitting congressman, a former governor, and the state auditor. Murray’s incendiary rhetoric lit up the Oklahoma prairies and he led in the first primary by almost 65,000 votes. Facing a run off election, Alfalfa Bill swamped his challenger by almost 100,000 votes.

The Great Depression had thoroughly depressed Oklahoma and Oklahomans. Murray buried his hapless Republican opponent in the general election. Murray had run on a platform of what he referred to as the “three C’s”, which allowed him to revile “Corporations, Carpetbaggers, and Coons”.

Taking office as the ninth governor of Oklahoma, Murray’s elation at having been elected melted into a realization of just how grave the situation was for the state. The State of Oklahoma was quite nearly bankrupt; tax collections had trickled to almost nothing. People didn’t have the money to pay their bills or buy food for their families, much less pay their taxes. Oklahoma had incurred a $5 million deficit when Governor William J. Holloway had tried to bolster the economy by creating jobs and providing a form of welfare for suffering citizens.

Oklahoma’s suffering became even more intense as the ravages of the Dust Bowl arrived. For those who lived through it, they could never forget the “black blizzards” that came roiling across the plains and prairies. Clouds of dust traveled from the Midwest to New York City. Severe drought made it impossible to plant and grow crops of any kind. Livestock died pitifully as animals bleated for water and food. People died as well.

The winter of 1932 saw things get worse, if possible. Out of some eight hundred thousand urban residents, more than three hundred thousand were jobless. Some 60% of the farming population were tenant farmers, meaning they did not own the land they worked. Oklahoma’s farm income declined 64% during the decade of the 1930s.

Humorist Will Rogers, Oklahoma’s most famous native son, gave benefit performances to raise $100,000 for relief of suffering in the Sooner State. Many families, left homeless by the Depression, eked out what living they could in caves, cardboard boxes, tents and shacks. Yet there were those who decried free soup kitchens, claiming it would attract transients. Governor Murray ordered St. Anthony’s, an Oklahoma City hospital, to keep its soup kitchen open.

One of Oklahoma’s biggest industries – – – oil production – – – saw prices plummet and barrels of oil were selling for record low prices. Alfalfa Bill ordered the oil producers to cease production, believing it would raise the price of oil. These were the producers of what was known as “hot” oil, meaning it was produced outside of state and federal regulations, or above the quota allowed. The hot oil producers refused and the hard faced governor called out the National Guard and declared martial law. Oil production stopped and the price immediately began to rise.

Murray used the National Guard like his own private army whenever he felt the need or his will was thwarted. During his four years as governor, Bill Murray summoned the guard into action forty-seven times.

The people of Oklahoma put their faith in Franklin D. Roosevelt, who swept every county in the state during the 1932 presidential election. Their faith was well placed and their Congressional delegation, led by Senator Elmer Thomas, nudged $40 million federal dollars into the Sooner State. Another $18 million came from the Civil Works Administration, which helped to provide jobs for hungry Oklahomans. The $58 million spent in Oklahoma at the beginning of the New Deal would equate to about $1.4 billion in today’s currency, yet it remained far short of meeting the needs of Sooners. It was not long before Governor Murray was feuding with President Roosevelt. The disagreements between the two became so intense the president removed FERA, Federal Emergency Relief Administration, from Murray’s control. The governor had insisted upon running the federal program as if it were a state agency and his personal fiefdom.

Alfalfa Bill Murray was hardly the only obstacle in Roosevelt’s political path in Oklahoma. Senator Thomas P. Gore was opposed to the New Deal and Governor Leon Phillips, elected in 1938, was profoundly opposed to the Roosevelt administration. It was Leon Phillips, when asked if he supported Henry Wallace for vice president at the 1940 Democratic National Convention replied, “Why, Henry’s my second choice.”

When asked who was his first choice, Phillips barked, “Anyone – – – red, white black or yellow – – – that can get the nomination.”

Oklahoma likely got less than it could have because so much of its political leadership was against the New Deal. Had it not been for Senator Elmer Thomas, Oklahomans would likely have suffered even more.

Constitutionally unable to succeed himself, Bill Murray had to leave the governor’s office in 1934. Oklahomans elected Congressman E. W. Marland as governor, who promised a “Little New Deal” for the Sooner State. Bill Murray had been elected governor precisely because of the suffering in Oklahoma, being the little man’s friend. He symbolically allowed the poor to use the land surrounding the governor’s mansion to plant gardens, but interfered with the delivery of money and services from the Roosevelt administration.

Finally out of office in 1935, Murray, smoking one of his trademark long black cigars, plotted his return to office. Perhaps some of his hostility to FDR and the New Deal came from his having made an ill-fated run for the Democratic presidential nomination himself in 1932. Murray had campaigned on his “Four B’s” slogan – – – “Bread, Butter, Bacon and Beans”. His campaign went nowhere.

By 1938, Alfalfa Bill was on the campaign hustings yet again, but his time had passed. Murray was no longer the most conservative candidate in the field, nor the most aggressively populist. The sixty-eight year old former governor, his suits rumpled and stained with tobacco juice, food and ashes from his cigars, was a picturesque figure, but not many Oklahomans took Murray very seriously any longer.

Murray ran third in the primary. That same year, Murray’s wife Mary Alice died in Oklahoma City. A retiring woman who was well liked by those who knew her, Mary Alice’s body lay in state inside Oklahoma’s Capitol, the first woman in the state’s history to be accorded that honor. It was one of the few times the highly opinionated, obstreperous Alfalfa Bill was largely silent.

In 1940 Oklahoma once again had an election for an At Large congressional seat and Alfalfa Bill campaigned hard, despite being seventy years old. He faced one of the most famous names in Oklahoma history: Will Rogers. The humorist had died in a plane crash years before, but his name was still so popular with Sooners that Congressman Will Rogers (no relation) won the primary easily and was elected statewide.

Alfalfa Bill’s last political hurrah was in 1942 when he challenged incumbent Josh Lee for the United States Senate. Amongst a host of lesser candidates, the former governor could muster less than 11% of his fellow Democrats.

William H. Murray continued to write books, usually on topics involving the constitution and race, but he had saved little for his retirement and eked out an existence in one of Oklahoma’s hotels. Ed Moore, a very wealthy oilman, elected to the United States Senate in 1942, would occasionally send the former governor a check, gently noting he still respected the service Murray had rendered to Oklahoma.

Alfalfa Bill lived long enough to see his son, Johnston Murray, elected governor in 1950. An ailing former governor Murray administered the oath of office to his son in January of 1951. William H. Murray could take some solace in his son having won the governorship, but his health was increasingly frail. In his last years, Murray was both largely deaf and blind and required assistance to accomplish the simplest things.

In October of 1956, the eighty-six year old Alfalfa Bill struggled with double pneumonia. Already very frail and incapacitated by a serious stroke, it was Alfalfa Bill’s last battle. Murray slipped into a deep coma and with two of his three sons by his bedside, the highly individualistic former governor passed away on October 15, 1956.