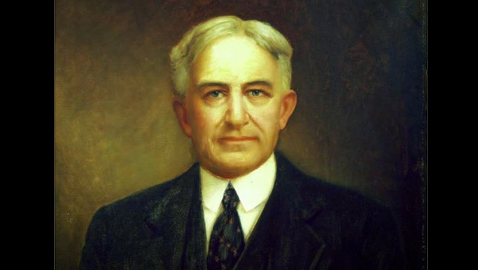

Henry Hollis Horton had once been one of the luckiest men in Tennessee politics. Horton had little political experience after beginning a law practice in Marshall County. Horton served a single term in the Tennessee House of Representatives and had been elected to the State Senate in 1926. Despite being a freshman senator, Horton’s colleagues elevated him to become Speaker of the Senate, which made him Tennessee’s lieutenant governor. That post became of prime importance when Governor Austin Peay died unexpectedly on October 2, 1927. Henry Horton was sworn in as Tennessee’s thirty-sixth governor after a “simple” ceremony in his rooms at the Andrew Jackson Hotel in Nashville. According to the Kingsport Times, Horton’s inaugural was “shorn of all dismissible formality” and only a handful of state officials and intimate friends witnessed Judge Arthur Crownover of the Court of Appeals, administer the oath of office, along with Mrs. Horton and their son, J. W.

Henry Horton seemed well poised to understand the common people of Tennessee, having been a small businessman. Horton owned a large farm, had taught school, operated a gristmill and had been director of a small-town bank. Horton had been elected superintendent of the Marshall County schools and served as a local alderman. The sixty-one year old Horton had married the former Adeline Wilhoit, the daughter of one of the largest property owners in Marshall County. Indeed, the Horton farm was so successful, Henry Horton had given up his law practice to manage his agricultural interests fulltime.

Still, Henry Horton was almost completely inexperienced in the art of politics, much less governing. Horton eagerly accepted the proffered help of Colonel Luke Lea. Lea, a former U. S. senator who had been defeated for renomination inside the Democratic primary in 1915 by Congressman Kenneth McKellar, owned the Nashville Tennessean, and sat atop an extensive media empire at a time when there was no television. The Tennessean was the flagship of Luke Lea’s publishing empire, which also included daily newspapers in Knoxville and Memphis. Lea owned a daily newspaper in each of Tennessee’s three grand divisions, which gave him a powerful voice in Volunteer State politics.

Lea had been highly influential in the administration of the late governor Austin Peay and while powerful, Lea was not always successful in bending Peay to his will. Peay was a strong-minded individual who was well able to resist Colonel Lea’s more base impulses. Much to Lea’s dismay and chagrin, Governor Peay refused to use the full power of his office for mere political purposes. Governor Horton would prove to have no such compunctions and remained heavily influenced by Lea throughout his administration. There was little doubt Horton intended to run in 1928 to win a term in his own right and the governor, along with Luke Lea, had powerful enemies, not the least of which were Senator K. D. McKellar and E. H. Crump, leader of the Shelby County political organization. McKellar and Crump, along with Mayor Hilary Howse of Nashville, backed State Treasurer Hill McAlister in the Democratic primary against Governor Horton in 1928. Lea shrewdly urged Congressman Finis Garrett to challenge McKellar for his seat in the United States Senate that same year. While Lea may not have believed Garrett could beat the formidable McKellar, he did realize it would force the senator to run an active campaign and divide the resources between the gubernatorial and senatorial races, which was a distinct advantage to Henry Horton. Peay’s reorganization of state government certainly did promote greater efficiency, but it also provided Governor Henry Horton with sweeping patronage powers, which he and Lea used ruthlessly to build support for the administration.

Those powers made Luke Lea the most politically powerful man in the state of Tennessee. Senator McKellar easily defeated Congressman Garrett, winning by better than 2 – 1 in the Democratic primary. The battle between Hill McAlister and Henry Horton was much closer. Governor Horton won by an eyelash, defeating Hill McAlister by just over 5300 ballots. McAlister ran strongly in the urban counties, winning Davidson and Shelby Counties by huge majorities and Knox County by a smaller margin. Horton actually managed to carry Hamilton County.

The governor’s victory gave Luke Lea control of the State Election Board, which was a significant threat to E. H. Crump’s dominance inside Shelby County. Ever a practical man, Crump soon made his peace with Luke Lea. In exchange for the Shelby County legislative delegation backing the Horton administration in the Tennessee General Assembly, neither the governor nor Colonel Lea would interfere with Crump’s domain. Naturally, Senator McKellar was hardly keen about Crump’s new alliance with Luke Lea. The senator never failed to remind Crump that Lea could not be trusted. Crump kept his word and supported Henry Horton for a second term in 1930 when the governor faced only token opposition. Yet shortly after the election, both state government and Tennessee politics would be rocked by one of the biggest scandals in the state’s history.

Luke Lea had been closely associated with Rogers Caldwell in business. Caldwell, once touted as the “J. P. Morgan of the South”, headed Caldwell and Company and launched the Bank of Tennessee. Nor was the Bank of Tennessee any mere bank, but the depository for Rogers Caldwell’s insurance bonds. It was Rogers Caldwell who helped Luke Lea acquire the Knoxville Journal and the Memphis Commercial Appeal.

Eventually Rogers Caldwell’s web of interests included ownership of “insurance companies, banks, textile mills, oil companies, department stores,” and other businesses, according to Professor Fred Colvin of Middle Tennessee State University. Caldwell’s bond business underwrote varied construction projects such as the building of hotels and office buildings.

Henry Horton was reelected governor of Tennessee on November 3, 1930 by Tennesseans and four days later came the shattering news the Bank of Tennessee had closed its doors. With the closure of the Bank of Tennessee, the state had lost almost $3.5 million in deposits. Other bank closures quickly followed, but it was the collapse of Caldwell and Company that sent shock waves throughout Tennessee. Once the greatest financial empire in the Southland, at least on paper, the fall of the House of Caldwell took more than 6.6 million (the equivalent to more than $102 million today) Tennessee taxpayer dollars with it.

The State of Tennessee was left with an unprecedented fiscal debacle and all eyes turned to Governor Henry Horton. Virtually everyone realized the governor’s two most influential backers had been Luke Lea and his business partner Rogers Caldwell. A committee was quickly formed of prominent Tennesseans, including former governor Albert H. Roberts, Lewis Pope, attorney Charles “Kit” McConnico, and more ominously, Horton’s former highway commissioner, Neil Bass. The fact Neil Bass was on the committee did not bode well for the governor, as Horton had engaged in a brutal public firing of the former commissioner. Governor Horton could do little more than issue a statement promising “a full and complete investigation of all departments.” Horton complained there had been numerous “untrue and misleading statements” made since the collapse of Caldwell and Company. The governor said he was “conscious of no dereliction of duty” on his part. Few people paid any attention to Governor Horton’s feeble excuses.

The Kingsport Times summed up the feelings of thousands of Tennesseans about Horton’s promised investigation: “What we are particularly interested in, however, is an investigation of Governor Horton himself…of his actions, his affiliations and his connections.”

H. Crump had said nothing and at least on the surface, his political alliance with Luke Lea appeared to be intact. Senator McKellar saw his opportunity and wrote to the Memphis Boss from Washington. McKellar said he was “intensely desirous you gentlemen in Shelby County take no step which might prove embarrassing to you in the future.” The senator said there were “some things no friend should be called upon to do” and urged Crump to drop his support of Lea.

Better than most, McKellar knew Crump’s alliance with Luke Lea had been one of convenience. Neither the Memphis Boss nor the Colonel liked one another; their entire history was one of mutual dislike and competition for power and prominence. Still, for the time being, Crump kept his own counsel.

H. Crump’s silence came to an abrupt end just after the first of the year when he demanded an “absolutely thorough and sweeping investigation.” The Memphis Boss headed to Nashville and soon bested the Horton administration’s candidate for Speaker of the State Senate. The Chattanooga Times quipped, “Mr. Crump came to Nashville on Sunday night as the boss of Shelby County. In two days’ time he was elected ‘boss’ of Tennessee politics.” It was an overstatement, but Luke Lea and Henry Horton were certainly gravely politically injured. It was the beginning of the fall of Luke Lea and the rise of the political ascendancy of Senator K. D. McKellar and E. H. Crump that would dominate Tennessee politics for almost two decades.

Crump spared the governor he had supported just months earlier nothing. Crump damned Henry Horton who he said “sat in his office, supine and docile” while the state’s coffers were looted. The Memphis Boss said Horton had been the “figurehead” for Luke Lea and Rogers Caldwell and demanded the governor be impeached when the legislature convened.

Writing more than forty years after the fact, Joe Hatcher, political columnist for the Nashville Tennessean reminded readers the investigation of Henry Horton’s administration had been derided by the governor’s supporters as “’the longest fishing expedition’ in the state’s history.” Hatcher claimed Henry Horton was “one of the state’s outstanding, most dedicated and serious-minded governors…” Yet Hatcher chortled the Crump stalwarts had gone to bed too early on election night when Hill McAlister narrowly lost to Horton in the 1928 Democratic primary “while Col. Luke Lea, Charles M. McCabe, Tom Greer and others stayed awake.” Hatcher recounted the story of Crump’s chief lieutenant Frank “Roxie” Rice had telephoned McAlister headquarters around 9 p.m. wondering how many votes the candidate needed to win. Rice was allegedly told, “We need 20,000 to make it safe.” “You’ve got ‘em,” Rice supposedly replied. The Crump machine reported its totals thinking the election was won. More candid in oral histories than in writing his political column, Hatcher laughed that Lea and his associates simply stole more votes than the Crump organization.

Eight articles of impeachment were brought against Governor Henry Horton, one of which was an odd charge about a piano purchased for the governor’s mansion. A titanic struggle ensued between the Horton administration and its opponents. Luke Lea and Henry Horton used every means at their disposal to win the votes of legislators to fend off the impeachment. Crump sputtered that if a legislator demanded one of the cornerstones of the Capitol Building, he could easily obtain it in exchange for voting against the impeachment of Henry Horton.

When the legislature voted on Article One – – – which was accusing the governor of having conspired with Luke Lea and Rogers Caldwell “to use state funds for private benefits” 58 legislators voted against it; 41 voted to find Governor Henry Horton guilty of the charge. The battle was over and Henry Horton still clung to the governor’s office.

It was a pyrrhic victory as while Henry Horton remained governor of Tennessee, he was a broken man. The 1932 governor’s race was won by Hill McAlister, allowing Senator Kenneth D. McKellar and E. H. Crump to began their long dominion of Tennessee politics. Luke Lea, his political power broken, would lose his media empire and eventually go to prison. Horton quietly left office in 1933 and returned to his farm in Marshall County. Henry Horton lived barely a year after leaving the governor’s mansion, succumbing to a stroke at his home on July 2, 1934. The former governor was only sixty-eight years old.