By Steve Williams

Phil Garner grew up in the small town of Rutledge in Grainger County and with the high school there not having a football program in the mid-1960s; his dad moved the family to Knoxville to improve his son’s chances of earning a college scholarship.

That move paid off big-time.

“My dad knew that I was a pretty good athlete and I wanted to play football,” recalled Garner recently from his home in Woodlands, Tex. “We couldn’t afford for me to go to college if I didn’t get a scholarship or I was going to have to go to work to help pay for it. So dad moved us to Knoxville after my sophomore year at Rutledge, giving me the opportunity to play football and get more exposure in baseball.”

Garner was Bearden’s starting quarterback in 1965 and 1966 and also played some in the defensive secondary, but it was in baseball that he earned a scholarship to the University of Tennessee and eventually a long career as a player and manager in major league baseball.

In the big leagues pretty much from 1973 through 2007, Garner didn’t have the opportunity to make many trips back to Bearden over the years, but his high school alma mater didn’t forget him, in fact it took great pride in his highly successful career and honored him by naming its baseball facility Phil Garner Ballpark.

“It was a really good feeling. I was flattered,” said Garner.

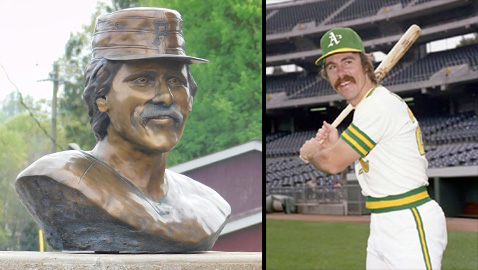

Six years ago, Bearden added a bronze bust of Garner to the front of its baseball facility and Phil was at the Bearden game when they dedicated the bust. He also watched the Bulldogs play a game at Alcoa on that trip.

“It was very enjoyable,” he said. “No, I don’t think anybody recognized me. I’ve got gray hair now and a gray mustache.

“I don’t look like I did in the baseball cards,” he added, laughing.

At Tennessee, Garner, who played second and third base, was a two-time All-SEC selection, the 1969 NCAA home run champion and a 1970 All-American.

Garner came back to UT in the offseason and earned his degree in Business Administration in 1973 despite being a first-round draft pick of the Oakland Athletics in 1971. His jersey number 18 was retired by UT in 2009.

Phil was a three-time All-Star in the majors as he played for Oakland, Pittsburgh, Houston, Los Angeles and San Francisco. That included the 1979 World Series when he hit .500 (12-for-24) and helped lead the Pirates to the title.

Garner was known as “Scrap Iron” in his playing days and shared how that came about.

“There are two versions to that story. When I got traded to the Pirates from Oakland, Hall of Fame announcer Milo Hamilton interviewed Willie Stargell and asked him about me.

“Stargell answered, ‘Well, he’s a little feller and he’s tough and he’ll compete. He’s like an old piece of scrap metal. You know, you can bend him and beat on him, but you can’t break him. And Milo responded, ‘Well, Scrap Iron then. That’s who he’ll be.’

“Milo started that moniker and of course the great Dave Parker I played with at Pittsburgh had another version,” added Garner. “He said the reason they call me Scrap Iron is because every time the ball hit my glove, the ball sounded like it was hitting the lid of a garbage can.

“Version one is a true story.”

Obviously, Parker and Garner liked to pick on each other.

“Dave was 6-7 and a gift to the Planet Athlete and we had a wonderful five years together,” said Garner. “But most of it, you would thought we were dead enemies because of the barbs that would go back and forth among us every day. Guys would come to clubhouse early just to listen and see what Dave and I were going to do. It was unbelievable.

“Oh, yeah, I got my shots in. And thank God Dave was a gentle giant because he would have killed me with one swipe of his big ole paws.”

Garner, who went on to manage Milwaukee (1992-99), Detroit (2000-02) and Houston (2004-07), now has a recreational ranch in Texas.

“We have some hay meadows,” he said. “We like to hunt and fish. There are several lakes on it, and it reminds me of East Tennessee with the rolling hills on it.”

Garner said he didn’t always want to be a manager, but he kept his options open.

“I started doing clinics and teaching kids. As I progressed in baseball, I thought I might want to be a general manager and the guy who ran the club in the business part of the game.

“When I got closer to the end of my career, I realized I was going to have the opportunity to coach and then manage. I really felt like that was more of my calling.”