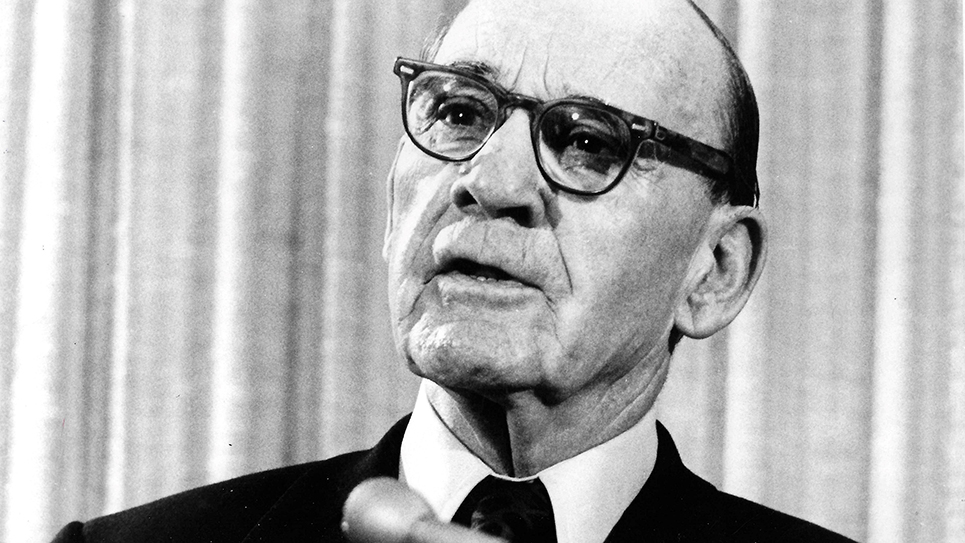

Senator K. D. McKellar points to an article about Memphis Boss E. H. Crump. Photo from the Nashville Banner Archives, Tennessee State Library & Archives.

Kenneth McKellar was Tennessee’s senior United States Senator and had been reelected easily in 1934 for another six-year term. McKellar had carried with him his junior colleague Nathan L. Bachman and Governor Hill McAlister. The alliance between McKellar and E. H. Crump, leader of the Shelby County political machine had again asserted its dominance in Tennessee elections.

By 1936 there were rumblings Senator McKellar and the Memphis Boss were at odds. The partnership of McKellar and Crump was as complex as their respective personalities. The two shared an obvious interest in politics, as well as a passion for horse racing. Both men were also highly sensitive to real and imagined slights and both were dominant personalities. Crump could be quite petulant, especially when he felt he or the Shelby County organization were being ignored. McKellar was usually quite considerate of the Memphis Boss’s feelings and patiently responded to Crump’s complaints.

Governor Hill McAlister wanted a third consecutive two-year term in 1936, but had proposed a sales tax, which was anathema to Crump. The Memphis Boss roundly denounced McAlister and made it quite clear he would not support McAlister again. Senator McKellar, who was much closer to McAlister, was prepared to back the governor for reelection but McAlister decided not to be a candidate again.

McAlister disappeared from Tennessee politics after leaving the governor’s office. The former governor received an appointment as Counsel to the Bituminous Coal Commission in Washington, D. C. through Senator McKellar in 1936. In 1940, McAlister became a referee in Nashville’s bankruptcy court, likely another position secured for him by McKellar.

Former West Tennessee Congressman Gordon Browning was already preparing a campaign for the gubernatorial nomination after having lost his first statewide race to Senator Nathan L. Bachman in 1934. Senator McKellar had taken an intense dislike to Browning when the former Congressman had actually contemplated running against him. McKellar naturally did not look favorably upon any Browning candidacy and the senator harbored suspicions Browning had not given up his senatorial ambitions.

Senator McKellar was clearly interested in seeing Gordon Browning defeated and settled on Burgin Dossett of Jacksboroas a candidate for the gubernatorial nomination. Dossett had been the Superintendent of Campbell County Schools before accepting a position in the Federal government extended to him by Senator McKellar. Once McKellar endorsed Dossett, most Tennesseans expected a similar announcement from Crump, although there was nothing coming from Memphis save for an ominous silence.

McKellar regularly pointed out what he felt to be Browning’s all too numerous shortcomings to Crump, but the Memphis Boss said nothing, as the primary campaign was well under way. Finally, Crump did the unthinkable and issued a public endorsement of Gordon Browning, which stunned Senator McKellar. Browning beat Dossett badly, which was seen as a blow to McKellar.

The vote in Shelby County during the Democratic primary was especially one-sided; with Browning winning almost sixty thousand votes to Dossett’s eight hundred and twenty-five. The exceedingly small vote for Burgin Dossett in Shelby County humiliated Senator McKellar and it may well be Crump spitefully wished to remind McKellar it was Crump who ruled in Memphis. While Crump certainly presided over his domain of Shelby County like an autocrat, there is ample reason to believe the Memphis Boss was somewhat jealous of McKellar’s personal popularity across Tennessee. Crump was also likely equally jealous of McKellar’ power in distributing patronage in Tennessee and frequently complained about officials whose allegiance was to McKellar alone.

Crump’s endorsement of Browning certainly sent Senator McKellar a message, but the Memphis Boss probably also thought Browning was likely to win regardless of whether he had the support of the Shelby County machine.

A flurry of speculation erupted that the break between Senator McKellar and Crump was permanent and some wondered if the Memphis Boss would support another candidate in 1940 when the senator would have to run again. McKellar ignored the rumors and bided his time, although he missed few opportunities to remind Crump that Browning was not to be trusted.

Crump became uneasy when Browning named Wallace Edwards Commissioner of Administration; Edwards had been the personal secretary to Governor Henry Horton and was close to Luke Lea, a bitter Crump opponent. Crump was even unhappier when Governor Browning appointed Lewis Pope as a special agent of the State of Tennessee to collect back taxes owed. That particular position was quite a lucrative one, supposedly providing Pope with an income of around $50,000 a year, a sum roughly equivalent to $750,000 today. Pope had twice run for governor against Hill McAlister and after losing the Democratic primary, refused to support the nominee and ran as an Independent in the general election. Pope had even allied himself with the Republicans in 1934 and had long accused the Shelby County machine of election fraud and corruption.

Another event shaped the future of Tennessee politics and further defined the relationship between Gordon Browning and E. H. Crump. Senator Nathan Bachman had been reelected to a new six-year term in November of 1936; Bachman died suddenly of a heart attack in Washington, D. C. after serving less than four months of his term. Governor Gordon Browning had the right to appoint a successor to the late Senator Bachman.

Browning went to Memphis to meet with Crump to discuss the senatorial appointment and other political matters. Both Crump and Browning revealed details of the meeting, but each had his own version of events. Browning claimed Crump wanted the appointment to the Senate; Crump disclaimed any interest in being appointed to the United States Senate. Crump had served in Congress for four years and had not especially enjoyed the experience, but it is quite possible the Memphis Boss would have liked for Browning to make the offer even if he intended to turn it down. According to Crump, Browning did offer to support Crump for the Senate, but in 1940 against Senator McKellar. Browning himself expressed interest in running for the Senate in 1938 for the remainder of Senator Bachman’s term.

The meeting between Browning and Crump left both men with the understanding their alliance had come to an end. Browning returned to Nashville and launched a major assault on the Memphis machine. Browning summoned the Tennessee General Assembly into special session on October 11, 1937. Browning gave the legislators bills to purge the voter registration lists, as well as create a county unit plan. The county unit plan was used in other states and worked something like the national Electoral College; whatever candidate carried a particular county would be accorded that county’s unit vote. In practicality it made the huge majorities in Shelby County for favored candidates meaningless. A statewide candidate could win the popular vote and still lose the election.

Crump was left reeling by the direct nature of Governor Browning’s war on the Memphis machine. He quickly marshaled the legislators from Shelby County to fight the governor’s bills and was forced to plead with Senator McKellar for help.

Kenneth McKellar would have been less than human not to take some measure of satisfaction from Crump’s plea; he had consistently warned the Memphis Boss about the possibility of treachery at the hands of Gordon Browning and now the Shelby County machine was in mortal peril. McKellar responded by coming to Nashville and addressed the legislature and denounced Browning’s legislation in typically blunt McKellar fashion. Both sides used every means to pass or defeat Browning’s proposals and the Memphis Commercial Appeal reporter opined the session was “as bitter as ever seen upon Capitol Hill.”

Governor Browning narrowly got his bill approved and called the General Assembly into yet another special session on November 8, 1937, ostensibly to approve a crime bill, but he also wanted approval of a bill to enlarge the State Election Commission, giving him the ability to appoint Election Commissioners favorable to him.

Browning was successful in his quest to take over the State Election Commission and proceeded to demand the voter rolls be purged. Crump fought back as best as he could and was elated when the Tennessee State Supreme Court struck down Browning’s county unit plan.

Governor Browning had also appointed a new senator, naming George L. Berry, long-time President of the International Pressmen’s Union, to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Senator Nathan Bachman. It was a curious appointment as Tennesseans were not especially friendly to labor leaders and Berry’s first action was to hire Browning’s older brother, F. L., as his Secretary.

Senator Berry received a frosty reception from McKellar and did nothing to improve relations between them by sending a letter proposing a division of patronage in Tennessee. As McKellar controlled virtually all patronage, it was a proposal that did not especially appeal to him. McKellar wrote Berry back to say he could not agree to any division of patronage.

George Berry proved not to be especially adept and found himself frustrated and outmaneuvered by the shrewd McKellar at every turn. McKellar also was quick to take advantage of Berry’s mistakes. President Roosevelt had summoned Governor Browning to the White House to discuss the senatorial appointment

There was good reason to believe Secretary of State Cordell Hull wished to be free of Roosevelt and return to the United States Senate. Hull had been corresponding with friends in Tennessee, quietly assessing his chances to displace Nathan Bachman in 1936. Judge James Gardenhire was encouraging Hull and Hull reported he had visited Senator McKellar to ascertain McKellar’s own attitude.

Hull did not run in 1936, but there were rumors he would welcome being appointed to the late Nathan Bachman’s Senate seat in 1937. Franklin Roosevelt did not want Hull appointed to the Senate, but he did want a senator who would vote for his court-packing plan. FDR’s “court packing” legislation was highly controversial and most presumed Senator Berry would be another sure vote for Roosevelt’s bill. Senator Berry was in the Senate chamber during the roll call, but refused to answer to his name while McKellar loyally supported the President. McKellar was quick to remind a very angry FDR his junior colleague failed to support the President. Roosevelt was so livid over the rebellion against his court-packing bill he determined to purge conservative Democrats from his own party and patronage in Tennessee was even more firmly in McKellar’s hands than ever before.

The fight between Gordon Browning and the McKellar – Crump alliance would prove to be one of the most hard fought and bitter in Tennessee’s tempestuous history.