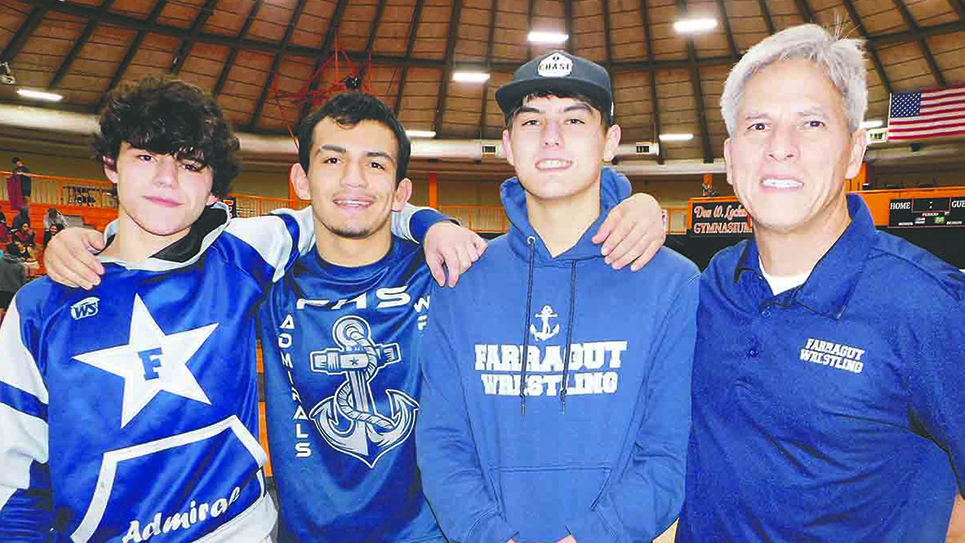

Photo from the Nashville Banner Archives, Nashville Public Library. From left to right, Governor Prentice Cooper, the governor’s mother, Mrs. W. P. Cooper, Senator K. D. McKellar and two unidentified gentlemen attending at luncheon at the Hermitage Hotel.

By Ray Hill

E. H. Crump, leader of the Shelby County political machine, had been bitterly disappointed by his favored candidate for the 1936 gubernatorial nomination, Gordon Browning. Crump and U. S. Senator Kenneth McKellar had disagreed over the gubernatorial candidates, causing a momentary lapse in their alliance. Crump had demonstrated his mastery of Memphis and Shelby County when Senator McKellar’s favored candidate in the Democratic primary received but 825 votes to almost 60,000 for Browning. Yet, when Governor Browning unleashed a massive assault upon the Shelby County machine, Crump was forced to turn to McKellar for aid and comfort.

Browning had proposed a county unit plan that would make the tremendous majorities in Shelby County meaningless in statewide elections; the governor had also submitted legislation that would expand the State Election Commission, giving him control of the state election machinery and had indicated he intended to purge the voter rolls in Shelby County. Crump begged McKellar for help, knowing the senator was one of the most respected political figures in Tennessee, if not the most respected figure. McKellar was also quite popular with many members of the General Assembly and like most Tennesseans, there were few legislators for whom McKellar had not done a favor.

Senator McKellar arrived in Nashville attired in full “morning” dress; a formal black coat and vest with striped trousers. McKellar denounced the Browning bills and urged their defeat. Browning used every resource at his command and a sitting governor has plenty of resources available. The governor dispensed state patronage freely, listening as legislators bargained with their votes. The governor managed to get his legislation through the General Assembly, only to see the Tennessee State Supreme Court strike down the county unit plan.

The McKellar – Crump alliance knew the 1938 elections would prove decisive in determining the balance of power in Tennessee politics. It would be one of the most brutal and hard fought campaigns in the state’s history. McKellar and Crump were certain to back candidates against Gordon Browning and U. S. Senator George L. Berry. Senator Berry had been appointed by Browning after Nathan L. Bachman had died of a heart attack in April of 1937, less than four months into a new six-year term.

Memphis Congressman Walter Chandler, sensing an opportunity, actually announced his candidacy for governor. Crump was uneasy about a statewide candidate from his own domain and Senator McKellar was not enthusiastic about Chandler. The Congressman was embarrassed when he was forced to withdraw shortly after making a declaration of his own candidacy. Crump, perhaps feeling somewhat embarrassed himself after having supported Gordon Browning in 1936, followed McKellar’s lead in selecting candidates to oppose the governor and Senator Berry.

McKellar was busily writing friends and political associates across the state in determining whom to support for either governor or U. S. senator. McKellar had seemingly settled upon Judge Winfield Hale of Rogersville for the Senate seat, but Hale didn’t wish to run. Chattanooga Congressman Sam D. McReynolds was anxious for promotion to the Senate and other potential candidates include Tom Stewart of Winchester, attorney Phil Whitaker, Congressman J. Ridley Mitchell of Cookeville, and several others.

Prentice Cooper was forty-two years old in 1938 and a little known state senator from Shelbyville. His father, William P. Cooper, was a wealthy attorney and banker and the Cooper family was highly esteemed. Prentice Cooper himself was so little known many thought his candidacy was launched so that he might be considered for a Cabinet post by the eventual winner. W. P. Cooper had been approached by some influential Democrats about seeking the gubernatorial nod and had replied he was not interested in running, but his son was eager to run. Senator McKellar knew W. P. Cooper quite well and induced Crump to lend his own support to Prentice Cooper’s campaign.

Prentice Cooper was, like McKellar, a bachelor at the time and shared another trait with the veteran senator, as he had something of a temper himself. Cooper was not an especially good orator like Governor Browning, but surrogates could do much of the speaking during the campaign.

To oppose Senator George L. Berry, McKellar settled on Arthur T. “Tom” Stewart, the District Attorney for a judicial district in Middle Tennessee. Stewart had been the official prosecutor during the famous Scopes “Monkey” Trial in Dayton, Tennessee. Once again, E. H. Crump promptly endorsed McKellar’s choice.

Unlike the gubernatorial primary, the race for the senatorial nomination was not to be a two-man affair, as Fourth District Congressman John Ridley Mitchell announced he was running too. Mitchell had been in Congress for eight years and sensed he might have an opening with the two warring factions beating up one another, much as McKellar had slipped into the Senate between Luke Lea and Malcolm Patterson.

George L. Berry proved to be not only a disappointment to his patron Gordon Browning, but also a severe political liability. Berry had not relinquished the presidency of the International Pressmen’s Union while a member of the United States Senate. Berry personally owned significant business interests, including a full color label printing plant and the largest farm in the entire southeastern United States. Berry also owned significant mineral rights in East Tennessee and was engaged in a feud with the Tennessee Valley Authority about the value of those mineral rights. Berry maintained the TVA had flooded property, which contained millions of dollars worth of marble and mineral rights. Dr. Harcourt Morgan, Chairman of the Tennessee Valley Authority, considered Berry’s claims to be not only outrageous, but also criminal. Senator Berry had also been one of the leaders of the movement to raise a tremendous amount of cash for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1936 reelection campaign, but his attitude towards FDR had changed dramatically by 1938. Berry campaigned as an opponent of Franklin Roosevelt and became critical of the New Deal, perhaps because FDR invariably sided with Kenneth McKellar in patronage matters in Tennessee.

Franklin Roosevelt remained highly popular personally in Tennessee and Berry’s criticism of the president was not well received by Democrats in the Volunteer State. Conversely, Tom Stewart ran as an all out supporter of President Roosevelt.

Both McKellar and Crump kept a careful eye on the candidates as the primary election progressed. The McKellar – Crump candidates ran as a ticket and Cooper, Stewart and W. D. “Pete” Haynes campaigned together across Tennessee. A state headquarters was opened in the Hermitage Hotel and manager John Harton sent a steady stream of letters to McKellar’s Senate office and Crump’s business office in Memphis, seeking advice, informing them of developments, and asking for help.

Senator McKellar’s replies to Harton revealed an encyclopedic knowledge of people and politics in Tennessee, which was not surprising considering he had been in the Senate for more than twenty years. McKellar knew personally the political landscape and players in Tennessee, but also in each of Tennessee’s ninety-five counties. McKellar, never one to shy away from taking a forthright stand, returned to Tennessee himself to take part in the primary campaign and made several speeches for Cooper and Stewart.

Crump had a particular genius for political organization and exhorted the Cooper – Stewart campaign to organize at every level. The Memphis Boss even went so far as to send Prentice Cooper a suggested platform, which Cooper politely acknowledged, but otherwise ignored.

Governor Browning, realizing he was fighting for his political life, seemed more desperate as the campaign raged across the state. He tried to make Crump and bossism an issue and began to sound rather shrill. Browning’s tactics to destroy the Memphis machine had brought down the wrath of newspaper editors across Tennessee on his head; even the Tennessean castigated the governor for his heavy-handed efforts. Browning tried as best he could to distance himself from Senator Berry, but as the governor had appointed Berry to the Senate in the first place and his older brother was working for Berry, it proved to be impossible to do.

Election Day brought overwhelming defeat to Gordon Browning and George L. Berry and the victory was so complete, it helped Senator McKellar and Crump to dominate Tennessee politics for another decade. Browning was eliminated as a threat to McKellar’s continued tenure in office and once again the senator had a friendly governor who would displace all the Browning appointees and control of the State Election Commission would return to McKellar and Crump.

The Memphis Boss had naturally noticed Prentice Cooper had ignored his suggested platform and the new governor had not been in office long before Crump was again writing Senator McKellar to complain. Crump fretted about McKellar’s appointees and Governor Cooper, pointing out many of the senator’s loyalists had been ignoring Shelby County in terms of patronage and contracts. Crump petulantly pointed out he had never wished to get involved in state campaigns, but had only agreed to do so because McKellar had urged him to participate. Crump flatly declared Governor Cooper to be a “wash out” and speculated the senator was satisfied with the arrangement as McKellar’s “lieutenants” would be for McKellar alone in 1940.

As usual, McKellar replied and assured Crump he would continue to cooperate fully and stated he had contacted some of the appointees the Memphis Boss claimed were ignoring Shelby County’s interests and soothed the Boss’s hurt feelings.

Mr. Wayne Dowdy of the Shelby County Public Library in Memphis has written extensively about E. H. Crump and Senator McKellar when the Crump family finally donated the Memphis Boss’s personal and political papers to that institution. Mr. Dowdy has written some excellent articles and books using the Crump correspondence as a resource and has contributed much to history with his efforts.

McKellar and Crump’s alliance continued to hold together as 1940 and the presidential election approached.