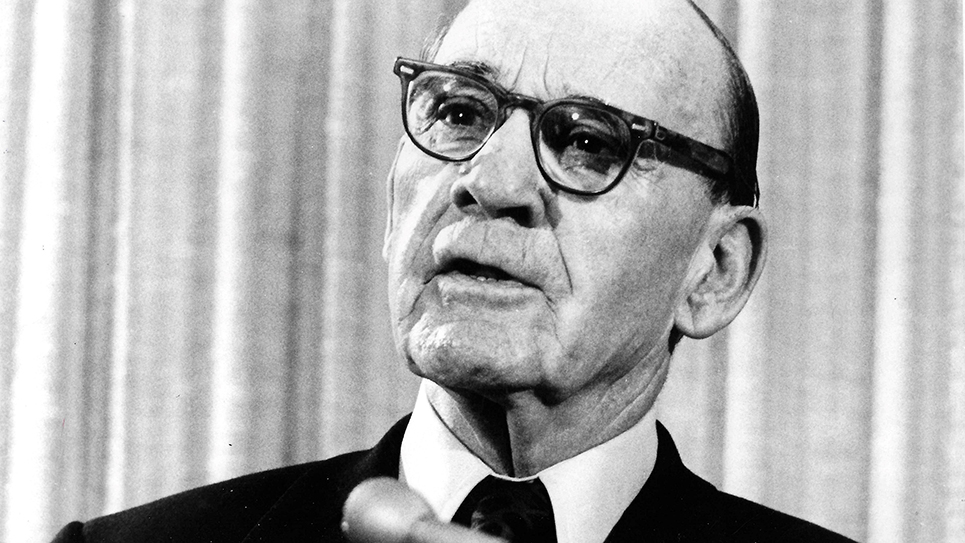

Senator Kenneth McKellar and Georgia U. S. Senator Walter F. George attending a meeting of the Democratic Conference Committee, 1943. Photo from the author’s personal collection.

By 1940, Kenneth McKellar had represented Tennessee in the United States Senate longer than any other man. At seventy-one, the senator showed no signs of slowing down, much less retiring. McKellar loved his job and was quite good at it. It was quite clear he would seek a fifth term in the United States Senate.

With World War II already raging in Europe, Franklin Roosevelt watched events with a wary eye, knowing it was a matter of time before the United States was involved, but his actions were tempered by the strong isolationist sentiment in America. The isolationists had numerous powerful spokesmen in Congress, including Montana U. S. Senator Burton K. Wheeler, Missouri U. S. Senator Bennett Champ Clark, California’s Hiram Johnson and many others. The isolationist campaign, designed to keep America out of European wars, was hardly confined to Congress. Many prominent Americans strongly supported the America First movement, which was especially strong in the Midwestern part of the country. Charles Lindberg, the world famous aviator, was one of the more notable spokesmen at America First rallies all across the country. Support for America First was not confined to the Republican Party, as many influential Democrats were staunch isolationists. David I. Walsh, the first Irish Catholic Democrat ever to be elected governor and United States Senator from the Bay State, hated the British and from his perch as Chairman of the Senate’s Naval Affairs Committee, kept FDR from going too far to help Britain, which was then desperately struggling under the Nazi onslaught. Walsh was an interesting character and believed to be gay by many in Massachusetts. In fact, one Massachusetts industrialist once said of Walsh, he would trust the senator to accompany his daughter on a cruise around the world, but wouldn’t trust Walsh in a canoe crossing a creek with his son.

Senator McKellar and Senator Tom Stewart both strongly supported FDR’s foreign policy, including the Lend Lease program, which accomplished much to aid the hard pressed British Empire. Neither Senator McKellar nor E. H. Crump especially liked Franklin Roosevelt personally; both acknowledged FDR’s considerable political skills, as well as his deviousness and willingness to lie when it suited him. Allen Drury, a young reporter for the Associated Press during the 1940s and best selling author of Advise and Consent once told me years ago that Senator McKellar’s sulfuric private comments about President Roosevelt could never be printed in a family newspaper. Still, McKellar issued a strong statement endorsing Roosevelt for a third term, which no man had ever had in American politics. At the time, there was no legal prohibition for a president not to seek a third term in office, but most had followed the example set by George Washington and retired after two terms. Franklin Roosevelt, knowing there would be considerable opposition to his seeking a third term as President of the United States, played a shrewd game as the nominating conventions approached.

Roosevelt gave no indication he was actually a candidate for the Democratic nomination and booms started for other candidates, none of which gained much traction. FDR himself repeatedly stated his only desire was to return to his estate on the Hudson River in upstate New York. Vice President John Nance Garner, former Speaker of the House of Representatives, and a salty old campaigner, opposed the idea of a third term for anyone and was himself an official candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination. “Cactus Jack” didn’t get much of anywhere with his candidacy and other members of FDR’s administration harbored presidential ambitions. Cordell Hull, Secretary of State, was frequently mentioned, but secretly suffered from Sarcoidosis, a serious illness oftentimes confused with tuberculosis. Hull was also seventy years old at the time and McKellar’s announcement backing Roosevelt helped to stall any bandwagon in Hull’s home state of Tennessee.

James A. Farley, who had managed Roosevelt’s 1932 presidential campaign, had been named Chairman of the Democratic National Committee as well as Postmaster General by a grateful FDR. The association between Farley and Roosevelt had been quite close, but despite being an Irish Catholic (and therefore considered unelectable by most Democrats), Farley wanted to be president himself. Roosevelt’s own son Elliott went to the convention as a delegate pledged to vote for Farley.

Many Democrats were frankly terrified of the prospect Franklin Roosevelt might actually return to his estate on the Hudson River. FDR had proven to be the best vote getter the Democratic Party had seen and many were fearful the Roosevelt coalition would fall apart without the president at the top of the ticket. FDR coyly made no declaration of his candidacy; in fact, he made it quite clear he was not running. Democrats gathering in Chicago for the Democratic National Convention erupted into wild cheering when a mysterious voice came over the loud speakers, chanting, “We want Roosevelt! We want Roosevelt!”, a cry soon taken up by most the delegates. Frenzied Democrats soon “drafted” Roosevelt to run again.

As Vice President Garner had opposed FDR and stated he was going home to Texas regardless of the outcome of the race, it was a forgone conclusion there would be a new vice presidential nominee. FDR surprised and infuriated many Democrats with his announcement he had selected Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace to be his running mate. Wallace had been, of all things, a Republican before being appointed to Roosevelt’s Cabinet. Wallace had never held elective office in his life before and was considered by many to be a mystic or worse.

Democrats mutinied and Speaker of the House William B. Bankhead was nominated for the vice presidency to oppose Wallace, as were several favorite son candidates. The rebellion was so serious FDR himself had to emphatically state he would turn down the presidential nomination if the convention refused to ratify his choice of a running mate. Enough Democrats were frightened by FDR’s threat to help Wallace edge out Speaker Bankhead for the vice presidential nomination.

The Republicans had nominated a dark horse candidate for the presidency, Wendell Willkie, a choice that Senator McKellar found especially loathsome. Willkie had been affiliated with the private power interests for most of his career, which both McKellar and Crump saw as a significant threat to the Tennessee Valley Authority. Crump mentioned to McKellar in a letter his belief the “TVA in Tennessee will go” if Willkie happened to be elected, a view McKellar shared. McKellar told Crump he didn’t believe Willkie had any better chance to be elected than Alf Landon in 1936 when Roosevelt won every state in the nation save for Maine and Vermont.

Crump issued his own statement strongly backing FDR, which Senator McKellar pointed out to the president and assured Roosevelt he had nothing to worry about in Tennessee. Neither did McKellar.

McKellar was running for his fifth term in the Senate and opponents despaired of beating him and only the eccentric Dr. John R. Neal entered the primary to challenge the old senator. Governor Cooper had only slightly more serious opposition in the form of Knoxville Mayor George Dempster. McKellar crushed Dr. Neal, winning 230,000 votes to Neal’s nearly 15,000 votes, giving the senator almost 94% of the ballots cast in the primary. Governor Cooper did only marginally less well in his own campaign against Dempster.

The Republicans had nominated Howard Baker, Sr. of Huntsville to oppose McKellar, father of future U. S. Senator Howard H. Baker, Jr. The election must have sparked some interesting conversation around the dinner table as Senator Baker has pointed out his Great Aunt Mattie Keene worked for Senator McKellar. Baker recalls visiting Washington, D. C. to see his Aunt Mattie whom he described as being quite liberated for the time as she smoked, drank and swore as well as any man.

McKellar understood Republicans in Tennessee represented no real threat to his continued service in the Senate and spent most of his time campaigning for Franklin Roosevelt. Once again the Democrats campaigned as a ticket and McKellar and Cooper won easily, as did Roosevelt.

It was during the decade of the 1940s that McKellar began to earn his reputation as a serious and accomplished feudist. McKellar had been a successful attorney before his election to Congress and was thoroughly capable of ambushing an unsuspecting witness before Congressional committees. It was K. D. McKellar who had publicly embarrassed FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, by forcing a sheepish admission from Hoover he had never personally made a single arrest in his career as a law enforcement officer. That particular exchange so chagrined the Director that he insisted being on the scene personally when the FBI cornered criminal Alvin Karpis in New Orleans. Hoover took credit for the arrest, making sure an account of his bravery reached the press, an account Karpis himself hotly disputed later. According to Karpis, Hoover remained hidden until he had actually been arrested by an agent; only when it seemed perfectly safe to do so did Hoover emerge to claim credit for the arrest.

Hoover was quite used to being treated deferentially by the Congress and had been stricken by having to admit he had never made an arrest and was even angrier when McKellar attempted to cut the operating budget of the FBI. Needless to say, relations between the secretive FBI Director and Senator McKellar were to remain strained for decades to come.