Huey Long was, by almost all accounts, a brilliant lawyer. To whom did he turn when he needed a good lawyer? The answer would be John Holmes Overton of Alexandria.

John H. Overton was a descendant of the famed John Overton of Tennessee, a contemporary of Andrew Jackson. Overton’s father Thomas was a judge and politics ran in his blood. Born in Marksville, Louisiana on September 17, 1875, John Overton went on to attend Louisiana State University, as well as Tulane’s law school.

At twenty-three, John H. Overton had his law degree and moved to Alexandria, where he became the city attorney and was a partner in a legal firm. In 1905, Overton was prosperous enough to marry Ada Ruth Dismukes and their union produced three daughters and a son. One of Overton’s daughters, Ruth, would serve as his administrative assistant while he was in the U.S. Senate.

John Overton’s early forays into politics were not successful. He ran for the United States Senate in 1918, but lost. While Overton ached in his bones to serve in Congress, it was not until he aligned himself with Huey P. Long that Overton’s political fortunes began on the upswing. When Huey faced impeachment in 1929, John Overton was one of several lawyers representing the beleaguered governor. It was not long thereafter when Overton’s political ambitions began to be gratified. When Congressman James B. Aswell died in office, Overton became Huey Long’s candidate for Congress in the Eighth District of Louisiana. Overton won and served a single term in the House.

John Overton’s political rise was rapid, as he became the Long candidate for the United States Senate in 1932 against incumbent Edwin S. Broussard. “Couzan Ed” was from the southern French parishes of Louisiana and while not overly popular, had been durable.

Huey Long had beaten Louisiana’s senior senator, Joseph E. Ransdell, two years previously, but had refused to vacate the governor’s office as he loathed the idea of his lieutenant governor succeeding him. The Long machine put all of its considerable resources behind Overton, who was an entertaining speaker and courtly man. “Couzan Ed” lost decisively and promptly filed a complaint with the Senate insisting he had been the victim of election fraud. After a lively investigation, John H. Overton was seated.

Senator Overton was, as to be expected, overshadowed by the flamboyant Huey until Long’s assassination in 1935. Overton worked hard at his job, enjoyed the congenial atmosphere and was popular with his colleagues. Senator Overton concerned himself with those issues that involved his home state and became especially interested in flood control. Overton became something of an expert in flood control and waterway issues.

Despite Huey Long’s death, John Overton was popular enough to be reelected easily in 1938. Stout, dignified, and well dressed, Senator Overton had risen to the top of Louisiana politics not only due to his friendship with Huey Long, but also because of his intelligence and ability to scrap. John H. Overton minced few words when riled. (The tempestuous Overton, during a heated exchange with Ohio Republican Robert A. Taft, Senator Overton thundered at his startled (and balding) colleague, “Don’t shake your gory locks at me!”) Overton never hesitated to take part in his home state’s political wars even when he was not on the ballot. Louisiana’s politics was always hard fought and frequently personal. Overton was one of the very few candidates who had friends in just about every faction’s camp.

By 1944, the sixty-eight year old senator’s health was beginning to falter. Overton announced he would not be a candidate for a third term. In a prepared statement given to reporters for Louisiana newspapers on March 13, 1944, Senator Overton said he would not run again.

Overton’s announcement came as a surprise, especially as he had participated in the gubernatorial election and had made it clear he would indeed be a candidate for reelection. Overton gave no reason for his sudden decision, save for his desire to return to his home in Alexandria.

John D. Ewing, publisher of the Shreveport Times and several other Louisiana newspapers, wrote a lengthy editorial urging John Overton to reconsider and run again. Ewing cited a litany of Overton’s accomplishments on behalf of Louisiana and urged Louisianans to support the senator. Some forty-six of Overton’s colleagues in the United States Senate signed a letter urging him to run again.

Senator Overton was positively horrified when former governor James A. Noe declared he would run for the Senate.

Overton said the Old Regulars had been committed to his own candidacy had he chosen to run again. Noe seemed to confirm that, saying his endorsement by the Old Regulars was only should there be an open Senate seat. It was not long before Noe issued a statement saying he would withdraw as a candidate should Overton change his mind and run for reelection. Noe said with World War II raging both in Europe and in the Pacific, many Louisianans believed due to Overton’s “long and valuable service” the senator should run again. Noe said he felt sure Overton would agree to run if he did not have to wage an overly taxing reelection campaign.

On July 6, 1944, John H. Overton was back home in Alexandria and declared he had changed his mind and would run for a third term. The senator conceded he was giving in to a “statewide demand from all factions” that he be a candidate again. Overton said the numerous conversations and communications he had received from his people had “induced me to reconsider my first decision and to leave it to the electorate whether I should continue in my present office.”

Senator Overton said he expected he would be handicapped in his campaign by not traveling across Louisiana, but felt it important for him to remain in Washington much of the time due to the war.

Senator Overton campaigned largely from Washington, making a series of radio addresses broadcast over Louisiana from the Capitol. Overton stressed his influence and seniority.

“If I were to leave the Senate, who from Louisiana would be able to continue where I left off?” Senator Overton wanted to know. “Who would be chairman of the flood control and river and harbor committee?”

The senator pointed out that his plan for controlling the flooding along the Mississippi River was being “executed”, but he reminded his listeners that as a member of the Senate’s Appropriations Committee, he had helped to secure $19,000,000 for 1944 and $26,000,000 for 1945 designated for flood control. Overton said the money had yet to be spent and it was necessary for him to remain in the Senate to make certain the appropriations were actually made and spent. Overton detailed the many legislative battles he had fought on behalf of Louisiana and that he was ready to continue his fight.

Facing several minor opponents without the stature or funding to seriously challenge an entrenched incumbent, Senator Overton was easily renominated in the Democratic primary, which was tantamount to election in Louisiana.

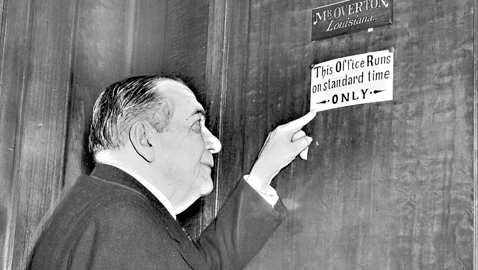

One of John Overton’s pet peeves was the institution of daylight savings time during World War II. Senator Overton bitterly fought the imposition of daylight savings time each year when the Senate considered the time change for the Capitol. Overton, his voice dripping with sarcasm, threatened to place an advertisement in newspapers in the lost and found section, stating, “Lost – – – somewhere between sunrise and sunset, one golden hour, set with 60 diamond minutes. No reward is offered; it is lost forever.”

Overton refused to abide by the decision of his colleagues; his Senate office would never run on the hated daylight savings time. Eventually, he posted a sign on the door to his suite in the Senate Office Building with a notice, “This Office Runs on God’s Time.”

Overton snorted that residents of Maryland, bordering the District of Columbia, would need two watches, one for their own time and another for the Capitol, which would be operating on daylight savings time.

When South Carolina Senator Burnet Maybank queried Overton how would anyone know how to catch a train, as the schedules would be thoroughly confused, the Louisianan retorted, “I do not know. If one takes a bus to go to Silver Spring, Maryland, he will meet himself coming back.”

Eventually, Overton was the lone dissenter in the United States Senate against daylight savings time, but he never relented in his hatred of the time change. Overton’s colleague from Louisiana, Allen J. Ellender, had difficulty coordinating work with Overton on projects important to their state. Senator Overton arrived in his office an hour later than Ellender and left an hour earlier than the junior senator.

Senator Overton still meddled in Louisiana politics and endorsed the gubernatorial candidacy of former governor Sam Jones in 1947. As endorsements go, it wasn’t much of an endorsement. John Overton made his announcement while home in Alexandria and said his support for Jones was less due to particular enthusiasm for the former governor, but largely due to his desire to defeat Congressman James H. Morrison, who was a candidate for governor as well. The senator said Morrison’s election would “be a misfortune and tragedy.”

The governor’s race was a typical Louisiana free-for-all with Earl Long, former governor Sam Jones, Judge Robert Kennon, and Congressman Morrison all running. Overton stressed he had no ill will towards Long, Kennon or Jones, but felt the former governor had the best chance of winning.

Overton politely accused Congressman Morrison of enjoying the support of organized crime.

“Can Morrison deny his campaign is supported by the gambling fraternity of New York and the gambling gang of New Orleans?” the senator wondered.

Morrison, enraged, replied the next day, saying the senator was a “guttersnipe purveyor of falsehoods and a doddering, senile old man.”

Senator Overton joined Congressman Hale Boggs in making a radio speech on behalf of Sam Jones, but the winner of the gubernatorial contest was the irrepressible Earl Long, the late Huey Long’s brother.

That same year, Senator Overton was feuding with another member of the Long family, Dr. George Long. Dr. Long was quite a character and had sent the senator a telegram critical of Overton’s vote in favor of the Taft – Hartley legislation. The telegram seemed somewhat cryptic to Overton who replied, “Your telegram unintelligible. Kindly explain.”

George Long sent yet another telegram, saying, “It simply means that you have quit the people who elected you to office.”

Overton sent the good doctor a blistering letter, noting Long had been the beneficiary of the senator’s aid, as well as some recognition he had received purely because he was the brother of Huey Long. Senator Overton contended that Dr. Long had little reputation of his own and whatever reputation he had was due “to your distinguished brother, because it has given you a slight political recognition, which you would not have enjoyed had you not shone, however palely, in the reflected glory of your brother.”

Dr. Long was a perennial candidate for office, a fact Overton noted, gloating that Long had never once been elected. To rub salt into the wound, Overton quoted Huey Long, “…you yourself may recall that he said, in effect, on the floor of the Senate, that he had a brother residing in Oklahoma who thought that he was a politician but who had never, despite repeated efforts, been elected to any office.”

Senator Overton concluded his letter, charitably saying his missive was not meant to be a “harsh criticism of you” but hoped it would cause Dr. Long to “make a reappraisal of yourself.”

John Overton would have been appalled by Dr. George Long’s election to Congress in 1952. Long remained in office until his death in 1958. Earl Long once told a friend that “Doc” Long was a “congenital thief.”

Senator Overton was seriously ailing by 1948. Suffering from a stomach obstruction, Overton went to the Bethesda Naval Hospital for emergency surgery. Evidently the operation was not a complete success, as Overton died nine days later on May 14, 1948 at age seventy-two.

As John H. Overton slipped away, his wife and daughter Ruth were with him. The senator’s body was taken home to Alexandria for burial. His family and nephew, Congressman Overton Brooks, made the long train trip from Washington, D.C. to Louisiana.