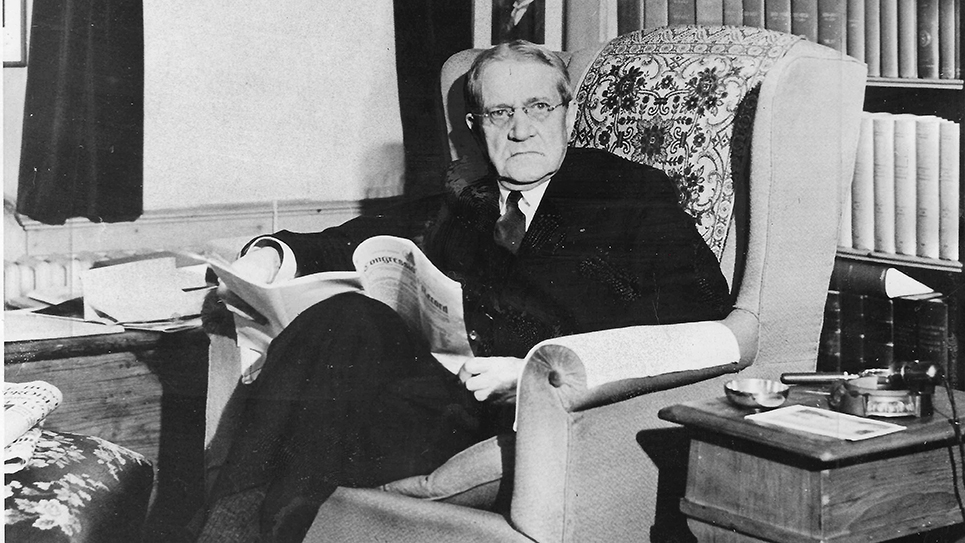

By 1939 Franklin Delano Roosevelt was fast approaching perhaps the biggest crisis of his presidency, aside from the Great Depression, with war looming in Europe. Roosevelt turned to his Secretary of State, Cordell Hull of Tennessee. Tall, stately, dignified and reserved, if not actually austere, Cordell Hull looked like a statesman, but Hull shared some notable characteristics with his one-time colleague, the peppery Senator Kenneth D. McKellar. Although Hull may well have had the appearance and outward demeanor of an early “Christian martyr” as Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes once grumbled, the Tennessean could be quite vindictive and held a grudge certainly as well as Senator McKellar. Perhaps it was not surprising that Cordell Hull would go to extraordinary lengths to settle a grudge with an enemy considering that his father had once hunted down a man who left him for dead and killed him. Like McKellar, Cordell Hull was an expert feudist. Despite his saintly appearance and soft-spoken nature, Hull was well known in Washington, D. C. for his ability to curse magnificently and his language caused some Capitol veterans to blush. Hull’s tongue lashing of the Japanese diplomats, riddled with powerful profanity, who had the misfortune to be in his office when he received news of the attack on Pearl Harbor, is legendary. Cordell Hull symbolized the rugged character of his old Fourth Congressional district in Tennessee. Like K. D. McKellar, Cordell Hull prized loyalty in others and returned it in kind. Also like McKellar, Hull could be blunt. Unlike Senator McKellar, Cordell Hull carefully protected and cultivated his public image.

Cordell Hull was a highly respected member of Congress long before anybody knew who Franklin Roosevelt was; Hull was first elected to Congress in 1906, winning the Democratic nomination by less than twenty votes. Reelected easily until 1920 when he was taken under by the national Republican landslide (the same year FDR was the Democratic candidate for vice president), Hull triumphantly returned to Congress in 1922 by whipping the tar out of the luckless incumbent GOP congressman. Hull’s prestige was such that he was elected Chairman of the Democratic National Committee after the party’s disastrous drubbing in 1920. Hull remained in office as Chairman of the Democratic National Committee until his resignation in 1924. In spite of a devastating defeat in the 1924 presidential election, Hull did manage to help Democrats improve their numbers in lesser offices, as well as eradicate a crushing debt. Cordell Hull was elected to the United States Senate in 1930 and served for two years before he was tapped by President-Elect Franklin Roosevelt to serve as Secretary of State. Hull was somewhat reluctant to accept the post, worrying about the financial obligations carried by a Secretary of State, not to mention his wife, Frances, disliked the idea of his leaving the Senate. Known as an expert in the fields of taxation and tariffs, Cordell Hull had not been especially interested in foreign policy, which made his appointment seem odd to a number of people. Those who knew Franklin Roosevelt believed his choice of Cordell Hull signaled his desire to direct his own foreign policy. FDR also knew that Hull was admired and respected by most members of Congress, which could do nothing but help him get difficult legislation passed.

While President Roosevelt did his best to reassure a frightened population during the Great Depression and tinkered with a faltering economy, Cordell Hull was busy initiating the “Good Neighbor” policy with Latin America. Most Americans were preoccupied with trying to keep their heads above water to notice another leader came to power in 1933; that was the year Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. Hitler proceeded to consolidate his power inside Germany and by the time FDR was overwhelmingly reelected to a second term in 1936, the German dictator was easily recognizable as a threat to the peace in Europe. Another threat to peace in the world was the Empire of Japan, which had gone to war with China in 1931 over a contrived incident designed to give the Japanese an excuse to begin hostilities. A Japanese lieutenant had planted a charge of dynamite to blow up railroad tracks, which were owned by a Japanese company. The blame for the explosion, which did little real damage, was the excuse needed for Japan to seize the Chinese province of Manchuria in 1931. Renamed Manchukuo by the Japanese, the last Emperor of china, Puyi, was installed as the puppet ruler of the province. Puyi was crowned Emperor of Manchukou in 1934, a title he retained until the end of World War II, but he remained only a figurehead.

The Japanese aggression in the Far East was noted by Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, the dictator of Italy; also noted by Hitler and Mussolini was the response of the democracies who did little more than denounce Japan for the invasion of China. By 1937, the Japanese were once again at war with China. Italy had invaded Ethiopia in 1935 and fully occupied the country by May of 1936. By 1938 Adolf Hitler had swallowed the whole of Austria in a relatively bloodless coup and threatened war over Czechoslovakia, necessitating the infamous Munich conference. The prime ministers of Great Britain and France met with Hitler and Mussolini and gave in to the German dictator’s demands for a slice of the Czech Republic, which had been carved out of the German Empire ruled by Kaiser Wilhelm II after World War I. The Sudetenland contained a majority of Germans, whom Hitler falsely claimed were being slaughtered by the Czechs. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and French premier Eduard Daladier signed the peace accord, allowing Chamberlain to infamously return home and proclaim there would be peace in his time.

Hitler’s appetite was appeased only briefly and on September 1, 1939, German troops and panzer divisions rolled across the borders into Poland. Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. Even with the outbreak of war in in Europe, a majority of Americans believed it was not a concern for the United States. Most Americans worried more about prosperity and putting their lives back together after the Depression.

Many of the most talented and able members of Congress were firm advocates of American nonintervention, irrespective of political party. Nor was isolationism confined to any one political viewpoint; in fact, most isolationists in Congress were progressives or liberals. Hiram Johnson, a famously progressive governor of California, had first come to the Senate in 1916 and had once been Theodore Roosevelt’s running mate on the Progressive or “Bull Moose” party label. Known for putting his principles well above politics, Johnson, according to one British scholar reporting to the Foreign Office, was an “implacable and uncompromising isolationist” who had bitterly fought President Woodrow Wilson’s dream of American entry into the League of Nations. The same British scholar summed up Senator Johnson’s view of Europe as “a sink of iniquity” and warned Johnson’s “prestige in Congress is still great and his parliamentary skill should not be underestimated.” Johnson had refused to support President Herbert Hoover for reelection in 1932 and was openly for Franklin Roosevelt.

William E. Borah, the “Lion of Idaho”, was another progressive Republican who had first come to the U. S. Senate in 1907 and had been a brilliant attorney. Borah was recognized by his colleagues as constitutional expert and was an orator of great capability, said to be one of the few senators who could actually change votes through his speeches. Borah had briefly considered challenging Herbert Hoover for the Republican presidential nomination in 1932, but discarded the idea when it became obvious he could not secure enough delegates to wrest the nomination from the incumbent. Borah had made a speech methodically attacking his own party’s platform in 1932 and refused to endorse President Hoover. Like his friend Hiram Johnson, Senator Borah had been utterly opposed to American participation in the League of Nations. Borah was a genuine maverick, obstreperously independent who had been easily reelected over a serious challenger (the incumbent governor of Idaho) in 1936, when most of his colleagues had been defeated and consigned to the dustbin of history. A former Chairman of the Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee and still the ranking Republican, Borah’s was an important voice inside the United States Senate.

Bennett Champ Clark was the son of the late Speaker of the House Champ Clark of Missouri. First elected to the Senate in 1932, Bennett Clark was an able and entertaining orator who thought fast on his feet. Clark was a master of ridicule, which he used effectively to berate his opponents. Isaiah Berlin, British scholar reporting back to Britain’s Foreign Office on figures in the American Congress, described Clark as “a rabid isolationist” who had “steadily voted against all the foreign policies and war measures of the Administration with the exception of the reciprocal trade agreement (in which the corn exporters of Missouri have some interest).” Berlin assessed Bennett Clark as an “avowed Anglophobe.” An able in-fighter despite his alcoholism, Senator Clark was an influential voice in American foreign policy, especially in the Midwest.

Robert LaFollette, like his friend Bennett Clark, the son of a famous father, Robert LaFollette, Sr. the progressive governor and U. S. senator from Wisconsin, was hardly the firebrand his father had been. The younger LaFollette was short, slightly pudgy, yet youthful looking. “Young Bob” was also a progressive Republican who had refused to back President Herbert Hoover for reelection. LaFollette had supported Franklin Roosevelt and was identified as a Progressive, who had defeated both Republicans and Democrats to remain in the U. S. Senate.

Burton K. Wheeler was a progressive Democrat from Montana who had bolted his own party in 1924 to run with the elder Bob LaFollette as a Progressive because he considered both the Republican and Democratic nominees as dangerously conservative. Considered so radical when he ran for governor of Montana in 1929, Wheeler had been labeled “Bolshevik Burt” by his opponents. Burton K. Wheeler was one of the few senators able to get under Franklin Roosevelt’s skin, although he had been one of the first to support FDR’s presidential candidacy.

Less respected inside the Senate than Wheeler, Gerald P. Nye of North Dakota was nonetheless highly voluble with a flair for attracting publicity to his favorite causes. Another progressive Republican who had bucked Herbert Hoover, Nye was described by Isaiah Berlin as “a notorious fire-eating Anglophobe Isolationist” who possessed “some influence” inside the Republican caucus. Berlin accused the North Dakota senator of having “Fascist” connections and working closely with Senator Wheeler and Senator Bob Reynolds of North Carolina, the closest thing to an isolationist from the South in the Senate. Even after the neutrality debates, Nye continued to support nonintervention. In fact, Gerald Nye was speaking at an America First rally when he was literally presented with the news Pearl Harbor had been bombed by the Japanese.

Henrik Shipstead, first elected to the Senate in 1922 as a Farmer-Laborite, was the son of Norwegian immigrants who still spoke with a slight Norwegian accent. A fiery orator and liberal who had been deeply opposed to the League of Nations, described by Isaiah Berlin as a “rabid Isolationist” and a “very narrow, bigoted, crotchety man…”

David I. Walsh, the first Irish Catholic Democrat to be elected governor and U. S. senator from Massachusetts, was another formidable speaker who was hostile to the British Empire like many of his fellow Irishmen. A well-dressed bachelor, Walsh was Chairman of the Senate’s Naval Affairs Committee.

The isolationist bloc in Congress was alert, articulate and powerful. President Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell faced formidable opposition when they set out to revise the neutrality laws of the United States in 1939.