Secretary of State Cordell Hull had finally made clear the position of the Roosevelt administration on revision of America’s neutrality laws. Before writing letters outlining the position of the administration to key committee chairmen, Hull had consulted with influential members of both the House Foreign Affairs Committee and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Hull had invited congressmen and senators to his apartment to discuss the proposed revisions of the neutrality laws. Newspaper reporters quickly noticed two ranking members of the House Foreign Affairs Committee had not been invited to Hull’s apartment at the Carlton Hotel. The Secretary of State had declined to consult either Hamilton Fish of New York or George Holden Tinkham of Massachusetts. Both congressmen were, not coincidentally, violent opponents of the Roosevelt – Hull foreign policy.

Hull had certainly given the Roosevelt administration’s supporters something to coalesce around, but he had also given the isolationists a target to shoot at. Within days of Hull’s announcement, Senate isolationists had dramatically declared they would filibuster to death any bill containing the Secretary of State’s recommendations. If necessary, they would form a “battalion of death” and fight to the last man. Despite the determined opposition of isolationists, Senator Pittman, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, seemed hopeful. “It is my belief that a majority of the committee will favor the principle” of the bill crafted around Secretary of State Hull’s recommendations, Pittman said.

The fundamental difference between administration supporters in Congress and the isolationists or noninterventionists was quite simple. Nobody was for war, but the noninterventionists saw themselves as being genuinely for American neutrality, while believing the Roosevelt administration was intent upon taking the country into war, one way or the other. The isolationists saw the proposed changes in America’s neutrality laws as specifically designed to aid Great Britain and France, which frankly they were. Irrespective of the rhetoric employed by the administration, President Roosevelt strongly believed propping up Britain and France against Germany was in the long term best interests of the United States. Senator Bennett Champ Clark said Hull’s plan “is simply calculated to lead us into war in the same way we were lead into the last war.”

Sol Bloom quickly called the House Foreign Affairs committee together, which rapidly began approving Hull’s recommendations. Senate Majority Leader Alben Barkley began to prepare to navigate the rapids of senatorial approval of Hull’s neutrality bill through the upper chamber. Barkley was worried, especially as he was hoping to adjourn the Senate by July 15. Hiram Johnson, Bennett Clark and Gerald Nye all threatened to filibuster the bill through the summer months and Barkley knew full well it was not an idle threat. An impending visit to the United States by British monarch King George VI and his Queen did little to help Barkley. If it did not help Barkley, the royal visit positively pained Sol Bloom. The visit of the King and Queen became an issue in the neutrality debate. Congressman James McGranery, a future Attorney General of the United States under President Harry Truman, announced he thought approximately seventy to seventy-five congressmen would refuse to attend the congressional reception in honor of King George and Queen Mary unless Sean Russell, a member of the Irish Republican Army arrested by the American Secret Service, was released.

Hull’s nemesis George Holden Tinkham of Massachusetts, doubtless thinking of his Irish-American constituents, told reporters, “The object of reporting that bill – – – which is not a neutrality bill and which is wholly drawn in favor of England—was to present the king tomorrow with the legislation.” Sol Bloom, horrified, snapped, “Such foolish statements will get any country into war.”

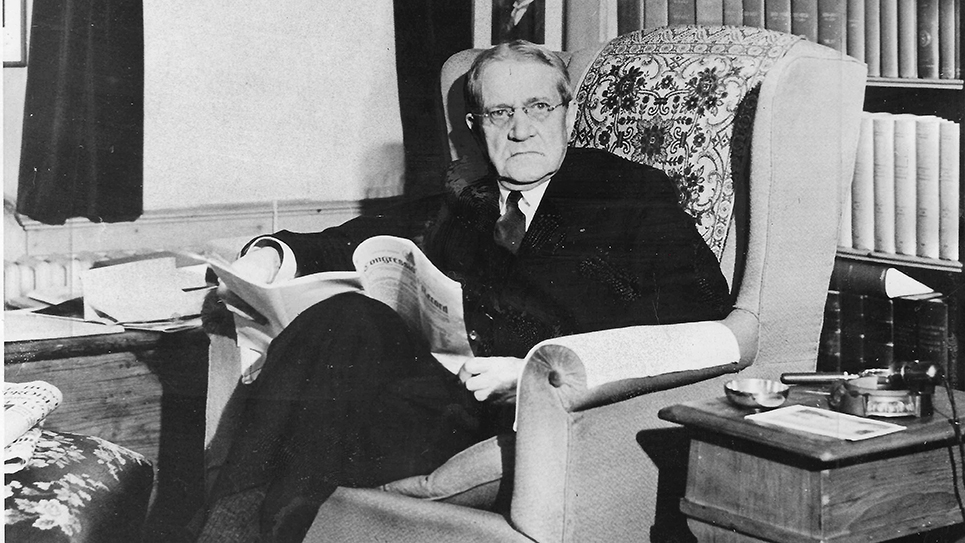

Congressman Tinkham was a colorful and striking figure, with a full beard and nattily dressed, who enjoyed going on safari in Africa and hunting big game. Tinkham, a Mayflower descendant, had been in Congress since 1915 and was unbeatable in his district and while he had been praised as “the conscience of the House” for his determined effort to protect the rights of African-Americans, Tinkham certainly had no affection for the British Empire. Profoundly opposed to anything he believed infringed upon personal liberty, Tinkham had been gleefully opposed to prohibition. The Massachusetts bachelor congressman became a particular nettle under the skin of Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Along with Hamilton Fish, George Holden Tinkham would be one of the loudest voices raised during the neutrality debate. Not one to be cautious, Congressman Tinkham alarmed the Democratic leadership in the House when he wondered aloud if the visit of King George “does in fact signify an entente or military understanding between the administration and the British government for the preservation of the British Empire at the expense of American blood and American treasure.” Tinkham said it would likely be a good idea for Congress to pass a resolution telling the world that the “United States is not the pawn and ally of the British Empire.”

Senator William Borah added his voice to the isolationist chorus, thundering, “If we pass legislation of this type, we will not be doing it to help ourselves but for the benefit of some other nations. We would be lending them our ability and our genius.” Borah stated his position succinctly. “I am opposed to selling manufactured war materials to nations at war—I would just as soon send them poison. I will never vote for it as long as I live.”

Alben Barkley was vague when asked about the prospects of the neutrality legislation. The Kentuckian opined the bill’s fate depended upon the action of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Sol Bloom was also having a difficult time managing his Foreign Affairs Committee in the House. Andrew C. Shiffler, a freshman Republican congressman from West Virginia, attempted to retain the arms embargo, an effort beaten back by administration supporters. Hamilton Fish, who was the congressman from President Roosevelt’s home district, tried hard to strike out language in the bill which the congressman insisted would “give the President more power than that given any President.” Fish was referring to the language in the bill that allowed the President to determine the areas deemed to be combat zones, from which American ships and citizens would be banned. Congressman Fish argued Roosevelt could arbitrarily say “in a case where Italy and England were at war, that Italy was not a combat area and England was not.” House Majority Leader Sam Rayburn of Texas was asked by reporters when the neutrality bill might reach the floor of the House. Rayburn did not know.

The strength of the isolationists was revealed in a close vote inside the House Foreign Affairs Committee on an amendment sponsored by Congressman John M. Vorys to replace the language in the Hull bill to enforce a mandatory arms embargo, which failed by a margin of 11 – 9.

Cordell Hull’s standing in the country was affirmed by the speculation about the 1940 presidential race, which was already swirling. Hull was being discussed as a logical successor to President Roosevelt and proud Tennesseans were already forming “Hull for President” clubs. The presidential boom for Hull had been inaugurated by the Wilson County Chamber of Commerce after adopting a resolution urging Hull’s nomination by the Democratic Party.

Cordell Hull had left Washington by train to greet King George and Queen Mary in Buffalo, New York as the royal pair crossed over from Canada into the United States. Hull boarded the royal train, which promptly headed for Washington, D. C. Their Britannic majesties had been seen off by thousands of Canadians, only to be greeted by very few Americans and Cordell Hull. Mrs. Hull, perhaps cognizant of the reaction by some congressmen, went out of her way to praise the royal couple. “She is such a charming person,. He is, too. They’re both as natural and courteous and gracious as can be,” Mrs. Hull said.

The administration suffered a blow when the House passed a modified version of an arms and munitions embargo shipments to belligerent countries. Cordell Hull said the House action was “a matter of regret and disappointment” but promised to continue to push the administration’s neutrality bill. Key Pittman was less restrained in his language, saying. “It seems that, unconsciously, many members of the house, actuated by antagonism (toward war) have really adopted a policy of ‘help Hitler’.” Speaker of the House William Bankhead of Alabama lamented to lift the arms embargo might “cause the trouble makers in Europe to draw the conclusion that there is not concerted action in this country between the executive and legislative branches on national policy.” Secretary of State Hull insisted the recommendations he made in revising the neutrality law were preferable to the changes made by the House of Representatives. Hull said he believed his proposal was “far more effective in the interest of peace and in keeping this country out of war than the present embargo law or any equivalent.” Hull refused to refer to the existing law as a neutrality law, but rather as an “embargo law.” The House voted shortly before midnight 200 – 189 to pass the modified embargo in the bill. The isolationist rejoiced with their victory. A dejected Sol Bloom murmured, “Whatever the house did tonight, I hope that divine providence guided it.” Charles A. Eaton, a New Jersey Republican sighed and said the House had acted “on it’s usual level of imbecility.”

The action of the House of Representatives naturally emboldened the isolationists in the Senate, who hailed the modified embargo provision as a defeat for the Roosevelt administration. Some senators believed the House had effectively killed Secretary of State Hull’s attempt to revise the neutrality law completely.

President Roosevelt, in Hyde Park, put the best face on the situation and made it very clear he wanted Congress to take action on the neutrality legislation. FDR also made it equally clear he strongly supported the position taken by Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Few chief executives have ever been as adroit or as entertaining as Franklin Roosevelt in fencing with the press. Asked by a reporter if he would urge the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to report out the neutrality bill as offered by Sol Bloom, FDR replied details were far less important than objectives. Queried by another reporter who told the President there were reports from the Capitol that Roosevelt was about to travel across the country to speak against certain members of Congress. FDR flatly labeled the report as “crazy.” Reminded that some senators had said they would talk through the entire summer if necessary to stop the revision of the neutrality law, President Roosevelt replied airily that was their prerogative if they wished to do so.

While the President bantered with reporters members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee met for a brief fifteen minutes, only to postpone consideration of Cordell Hull’s neutrality plan. The senators decided they would meet again in three days’ time, a Saturday, despite the desire of many members to adjourn. Senate Majority Leader Alben Barkley growled the Senate would remain in session until a bill was passed. Both Key Pittman and Senator Barkley predicted the Senate would reverse the action of the House and remove the arms embargo. Roosevelt had told Barkley and House Majority Leader Sam Rayburn he did not intend to move one iota from his request for additional discretionary powers. Secretary of State Hull issued a similar statement.

The isolationists, having tasted victory in the House, were equally adamant. The battle lines were drawn for the show down in the Senate.