By Pete Gawda

An area a few miles west of Knoxville that was once a peaceful farming community helped usher in the nuclear age. The story of how what is now the City of Oak Ridge came into being and the part it played in the Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb in World War II, is told at the American Museum of Science and Energy.

Oak Ridge was one of several sites across the country built to manufacture or assemble components of the atomic bomb. There are two stories told at the museum. One is the human story of how the area was transformed from a sparsely populated farming community to a bustling city of 75,000 workers and their families in two years’ time. The other is the technical story about the actual development and detonation of the bomb and the peaceful use of many of the byproducts of that process.

The human story is very important to the many people in the area who grew up there while their parents were working on a top secret project.

The museum tells the story in photographs and exhibits of how the farm people were moved off the land and a “Secret City” was built behind fences and gates “almost overnight.” The site of Oak Ridge was chosen because of its nearness to an abundant source of electricity produced by Norris Dam. At one time one seventh of the electricity produced in this country was used at Oak Ridge. Also, it was in a valley between two ridges, allowing for controlled access and better security.

To house the workers and family members, prefabricated housing was built and brought into the area in sections on flatbed trucks. Each house came with its own furniture and curtains. The houses all have flat tops and there was a variety of floor plans designated by letters of the alphabet. Hence they were called “alphabet houses.” They were also known as “cemestos” because they were built with cemesto panels, a building material made from sugar cane fiber insulating board surfaced on both sides with asbestos and cement panels. A two bedroom B – 1 model cemesto is on display on the museum grounds with a victory garden in its yard. Houses were moved in so fast that workers coming home in the evening sometimes had trouble finding their own house because no many new houses had been moved in that day. There were also dormitories and cafeterias for single workers. The rapidly growing town soon boasted a church, a school, a commercial district and police and fire departments.

The technical side of the story told by the museum resulted in many useful byproducts.

“It is not really about the bomb,” said David Hackett, a volunteer at the museum. “It is about ‘big science’.” He went on to elaborate on the beneficial things in use today that were developed at or for Oak Ridge including computers and nuclear medicine. An example of Hackett’s “big science” on display at the museum is a “moon box” which was developed at Oak Ridge to bring back rocks from the moon. Scientists at Oak Ridge explore and predict how the environment responds to stresses like climate change, industrialization and pollutants. Developments at Oak Ridge help communities respond to natural and man made disaster with tools such as data analysis and sensor monitoring.

“At the time the Manhattan Project was the largest industrial project in the world,” according to Mick Weist of the Oak Ridge Heritage and Preservation Association. As part of this project three parallel experimental processes for uranium enrichment and plutonium projection, necessary in the development of the atomic bomb, were developed. At the museum is a replica of “Little Boy,” the 9,000 pound atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, August 6, 1945.

Because of the urgent wartime situation, the entire project was clothed in secrecy. The people working on the project did not know what they were working on. The people who emptied the trash cans had to be illiterate so they would not know the importance of the documents they were destroying. There was such secrecy that the word “atom” disappeared from publication. Even the comic strip “Flash Gordon” was censored.

The museum has many hands on and interactive displays and exhibits that are especially interesting to children. In one room there is a giant model of an atom.

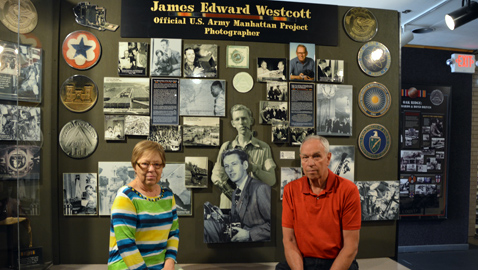

Contributing to our understanding of both the human and technical side of the museum are the many photographs of Ed Wescott that are on display. In 1942 he was hired by the Army Corps of Engineers to photograph every aspect of life in Oak Ridge. He was the only person legally allowed to have a camera at the top secret facility. “This story could not be told without him,” said Louise Presley of the Oak Ridge Heritage and Preservation Association.

The museum is located at 300 South Tulane in Oak Ridge and is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m Monday through Saturday and from 1 to 5 p.m. on Sunday.

There is so much to digest, it is hard to take it all in with one visit.