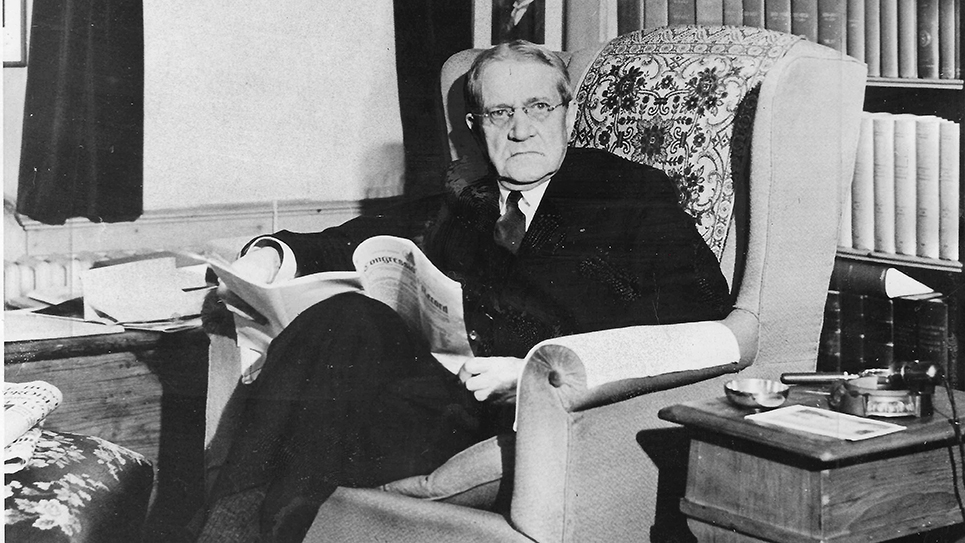

Dr. John Randolph Neal had some solid achievements under his belt, both as a state legislator and educator, yet there was growing dissatisfaction at the University of Tennessee. That dissatisfaction seemed to be confined largely to administrators, as Dr. Neal was apparently quite popular with his students. By 1923, those same administrators had decided to let John R. Neal go. To this day the reasons for Neal’s dismissal are unknown, although there are numerous theories and just as many opinions. Bobby E. Hicks, Neal’s biographer, concluded the most likely reason Dr. Neal was fired was “because of a personality conflict with the dean of the College of Law, Malcolm McDermott.” Dean McDermott was not happy with Neal’s personal appearance, indifference to bookkeeping, and unorthodox teaching methods. McDermott had complained to the president of the University of Tennessee, Harcourt Morgan, about Neal’s teaching methods “repeatedly.” Neal and six other professors were notified in June of 1923 they had not been recommended for reappointment; on July 17, 1923, they were told they had been fired. Officially, the decision was made by President Morgan, which was quickly affirmed by the Board of Trustees. When the university’s trustees came to Knoxville many of them were greeted by students who supported Dr. Neal in particular and when Governor Austin Peay arrived, he called for an open meeting. The previous meeting of the Board of Trustees confirming Neal’s firing had been held in a closed meeting.

None of the trustees dared refuse the request of Governor Peay for a public meeting, which was held at Knoxville’s Farragut Hotel. The meeting was described by Neal’s biographer as “bedlam” and with constant activity some thought it more resembled a “political meeting” than a sedate university affair. The governor patiently met with numerous supporters, both student and alumni, of Dr. Neal who protested his firing and begged that he be allowed to teach at the university. Numerous students spoke at the public meeting on Neal’s behalf and when the professor finally appeared he was greeted with thunderous applause. Dr. Neal was obviously deeply touched by the support of so many of his former students and had difficulty in controlling his emotions. Harcourt Morgan read fourteen charges against Neal into the record, many of which seemed trivial, while others appeared to be more serious. One of the charges seemed to indicate fundamental resentment towards Neal by the administration, noting the professor routinely sided with the students against the administration in any dispute. The charges included his dress, the fact he smoked in Ayres Hall, which was forbidden, and was lax in his work. Dr. Neal was given twenty minutes to refute the charges leveled against him. Neal hotly contested the allegations and pointed out he had never once missed a class in thirteen years while in Knoxville; in fact, he had come to his classes even when ill. John R. Neal pointedly asked Harcourt Morgan if the University president had ever come with any criticism of his performance. President Morgan had to confess that he had not. Neal insisted he was always within “earshot” of his students and classroom during examinations and noted that Dean McDermott was not in his own classroom while administering tests. Neal never denied that he had once changed the schedule for an exam, but said it was commonly done by other professors as well. Nor was he the only professor who violated the smoking ban in Ayres Hall, Neal snapped. Neal noted he had worked at the University of Tennessee law school for fourteen years and for part of that time, he had received not a penny of compensation. Neal claimed much of the credit for the University of Tennessee law school to be only the second in the South to be admitted in the National Association of American Law Colleges. Neal said he thought the University of Tennessee ought to be represented during a convention of law schools and urged Harcourt Morgan to send some one. President Morgan demurred, saying the university could not afford it. Dr. Neal went and paid his own way. Several students addressed the Board of Trustees; one student believed Dr. Neal was the “most beloved professor in the school…” At least one student stated Dean McDermott had never treated Dr. Neal with respect. The student praised John R. Neal as a professor who taught students to “think for themselves.” He added Dean McDermott’s own teaching style “could never make a successful law student.” It was all for naught as the Board of Trustees felt they had to uphold Harcourt Morgan’s decision to fire John R. Neal and the other professors. There was one very important dissenter: Governor Austin Peay. The governor bluntly said he did not like the methods used by the university administration to fire the instructors. Peay was careful to say he did approve of Harcourt Morgan, but was quite clear in saying he thought the reasons for the dismissals unjustified. Governor Peay voted against the dismissals, as did one other member of the Board. The pressure on the other Board members was clear, with one trustee saying he felt the decision was choosing between President Morgan or Dr. Neal, yet they could not keep both. There were efforts made to reinstate John R. Neal and a letter arrived from the dean of the University of Denver’s law school which gave the professor an unqualified endorsement. The dean credited Dr. Neal with “inspiring his students” which increased the interest of the students and caused them to do better with their studies. The University of Denver promptly offered Neal a full professorship, but he refused the offer.

The effort to have the University of Tennessee to rehire John R. Neal came to nothing. President Morgan disingenuously said he would be willing to have Dr. Neal back if the Board of Trustees were to change their minds. Morgan pointed out as the Board had no such intention, the matter was closed. Losing his job at the University of Tennessee’s law school crushed John R. Neal. The professor seemed unable to face friends and former colleagues and took pains to avoid them, even as they sought him out to provide friendship and comfort. Neal’s mental state was reflected in his personal dress and hygiene. If it was bad before, it became much worse after his having been fired. That was the cause for the management of the S & W Cafeteria to ban John R. Neal from the premises.

Neal recovered enough to launch a furious assault on the university, demanding the state legislature begin an immediate investigation. Neal growled that President Morgan was “legally, morally and mentally incompetent” to hold so high a position and responsibility. Dr. Neal charged Harcourt Morgan with having “instituted a system of terrorism at the university, both over the faculty and student body.” Neal even went so far as to question whether or not Harcourt Morgan was a citizen of the United States. Neal testified before the General Assembly and hit the university some hard blows. Dr. Neal noted one member of the Board of Trustees also happened to be president of the City National Bank. That University of Tennessee had deposits in the City National Bank and Neal pointed out state law forbade any member of the Board of Trustees from having a personal financial interest or deriving personal financial gain. Neal told legislators the University of Tennessee was the only such education institution whose president and virtually ever dean did not have Ph.D. degrees. Certainly Neal had gotten some measure of revenge and left more than a few UT administrators embarrassed. When the University of Tennessee announced in 1925 it would cease giving the annual John R. Neal Oratorical Award to the outstanding debate student it seemed little more than spite. Dr. Neal retorted he would bestow the award himself.

The legislature issued a report, but did nothing. Neal, persistent to the end, notified Governor Peay the Board of Trustees was not composed as required by law, as one-third of the members were required to be alumni. 1925 also saw Dr. Neal open the John Randolph Neal School of Law. To the horror and dismay of University of Tennessee officials, the John R. Neal School of Law was quite a success throughout the decades of the 1920s and 1930s. Dr. Neal eventually began graduating more students than the University of Tennessee law school. Neal continued to be both kind and careless, shuffling through checks for tuition and saying, “that boy can’t afford to go to law school” and tear it to pieces. By the 1940s, the John R. Neal School of Law was foundering. Doubtless the outbreak of war in 1941 made things difficult for the school, but the enrollment continued to declined until there were no students enrolled. Dr. Neal continued to operate the school without students until forced to close in 1943.

Few people today recall it, but John R. Neal participated in the trial of the century at the time. Dr. Neal was the attorney for John Scopes at the famous “Scopes’ Trial” in Dayton, Tennessee. The spotlight never quite hit John R. Neal as he was obscured by the legal talent and notoriety of Clarence Darrow and the oratorical abilities and political prominence of William Jennings Bryan. Yet not everyone overlooked John R. Neal or his abilities. The curmudgeonly writer, H. L. Mencken, the “Sage of Baltimore”, wrote that Neal was “an able lawyer and a man of repute” and opined that “in any Northern State his courage would get the praise it deserves.” Mencken sadly noted that “in Tennessee even the intelligentsia seem to feel that he has done something discreditable by sitting at the trial table with Darrow, Hays, and Malone.” Mencken complained and condemned the fact that the “state buzzes with trivial, idiotic gossip about him – – – that he dresses shabbily, that he has political aspirations, and so on.” Mencken concluded John R. Neal “has carried himself, in this case, in a way that does high credit to his profession and even higher credit to his native state. But his native state, instead of being proud of him, simply stabs him in the back.”