Every ten years legislative and Congressional districts must undergo some changes; redistricting always poses a danger to incumbents. It is not uncommon for a sitting congressman to run for higher office when faced with the elimination of his district. Congressman Albert Gore’s district was carved up in 1952, but he was already off and running for the United States Senate, making the job of the Tennessee General Assembly in redistricting the congressional districts much easier. In March of 1931, the state legislature completed its redistricting bill and headlines in the Kingsport Times blared “Rep. J. Ridley Mitchell Legislated Out of Office…”

The General Assembly had moved freshman Congressman Ridley Mitchell’s home county of Cumberland into the heavily Republican Second District. Tennessee had gone from ten congressional districts to nine following redistricting. State Representative W. Y. Boswell claimed the changes had been made to protect Congressman Ewin L. Davis of Tullahoma and at the expense of J. Ridley Mitchell.

Boswell had attempted to amend the bill to keep Morgan and Cumberland counties in the new Fourth Congressional district. “I don’t know of any reason to take Cumberland out of the Fourth district, except political reasons,” Boswell thundered. Boswell had asked his colleagues to put Cumberland County into the new Fourth District and “leave Ridley Mitchell and Judge Davis in the same district and let them fight it out.” Boswell was indignant as a colleague, Representative Maysilles, had frankly stated he wanted to see Cumberland County removed from the new Congressional district “to protect my congressman, Ewin L. Davis.”

Y. Boswell raised the specter that Ridley Mitchell, deprived of his seat in Congress, might become a candidate for higher office. Boswell shouted, “In sacrificing Ridley Mitchell you may make him governor of the state.” Republican legislator J. Tom Taylor laconically replied, “I think the Democrats are going to need a good candidate like Ridley Mitchell.”

Davis had served for almost fourteen years in Congress. Like Ridley Mitchell, Ewin L. Davis was a former judge. Davis was stately and dignified and looked the part of a congressman with a head of gray hair. The Tennessee legislature believed it had given Davis a favorable district and some were surprised when Ridley Mitchell moved into the new Fourth District and announced he was seeking reelection to Congress. Davis had already declared for another term and most political observers felt the veteran congressman would be impossible to beat within the newly configured Fourth District. A third candidate said he would enter the Democratic primary as well; J. P. Owen, was a former state senator who had run for Congress in 1930, but had been beaten by J. Ridley Mitchell. Like Mitchell, Owen moved from his home in Trousdale County to Rutherford County to make the race.

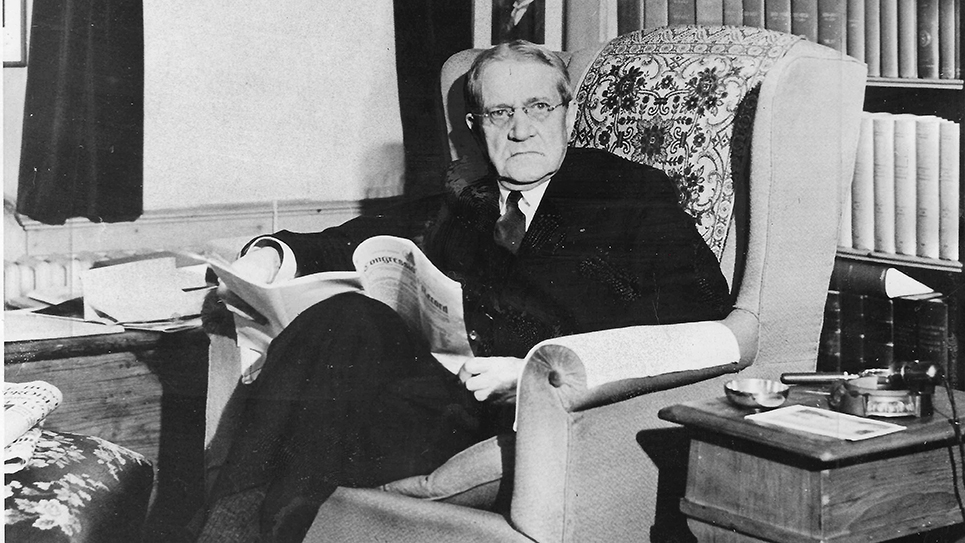

When the legislature had redistricted J. Ridley Mitchell out of his own Congressional district, he had been in Congress only a matter of days. Tall, bald and portly, J. Ridley Mitchell was not easily deterred. Mitchell, a bachelor, moved from Crossville to Cookeville, which was in the new Fourth District, a clear signal he intended to run against Ewin L. Davis for the right to remain in Congress. Mitchell also announced he would be opening a law office in the Herald Building in Cookeville.

While Ewin L. Davis was dignified and looked the part of a congressman, J. Ridley Mitchell was described as “Tennessee’s back-slapping, handshaking, joke-cracking” representative. When Mitchell first ran for Congress in 1930, some criticized him for his gregarious nature and personal contact with voters.

Mitchell retorted, “My only regret is that I don’t have four hands instead of two with which to shake your hands and slap your backs.”

Mitchell’s friends pointed out the congressman might be friendly, but he also possessed a serious side to his personality, pointing to his relentless nature while serving as a prosecutor and his shrewd business acumen as a banker. Mitchell also proved to be a mighty shrewd politician and in December of 1931, he announced he had selected Murfreesboro attorney John V. “Todd” Elrod to serve as his secretary or Chief of Staff.

Murfreesboro, in Rutherford County, was rich in votes in any primary election and had been a stronghold for Congressman Ewin L. Davis. Mitchell also knew how to promote himself through the newspapers and even the Tennessee General Assembly passed a resolution praising Senator Cordell Hull and Ridley Mitchell for their efforts in sponsoring legislation for a new veterans’ hospital for Middle Tennessee that same December. Mitchell also announced he was sponsoring a bill to provide for “village delivery” of the mail to Crossville and Lafayette, Tennessee. Congressman Mitchell pointed out his bill would not only provide better delivery of the mail, but it was also an “unemployment relief measure” as it would create four new postal positions in each community, an important point during the depths of the Great Depression. Ridley Mitchell was positively relentless in placing a flurry of legislation into the hopper, all with an eye toward the folks back home and less on passing any particular bill. Mitchell won praise from the Nashville Tennessean for a bill to appropriate $1 million per state for the “improvement of farm to market routes and rural post roads over which rural carriers travel.” The Tennessean gushed, “If he can get it passed this sturdy congressman will have built a monument to himself in many stout rural hearts, for such lowly roads are often neglected.” Whether intentional or not, the Tennessean also reminded its readers Ridley Mitchell’s Congressional district had been eliminated through the efforts of “city bosses”, meaning the machine of E. H. Crump in Memphis and that of Hilary Howse and “Kit” McConnico of Nashville.

While Congressman Ewin L. Davis remained relatively quiet, J. Ridley Mitchell proved to be single-minded in his pursuit of votes for the coming primary election. Yet another prominent Tennessean found a job through the auspices of Congressman J. Ridley Mitchell. Ed Goad, a commander in the local American Legion in Lebanon, Tennessee, won a post as clerk for a national committee through Mitchell’s efforts, which doubtless pleased Goad’s friends in Wilson County. Congressman Mitchell got more publicity from the Tennessean when Prentice Cooper, a politically ambitious state commander of the American Legion, headed a delegation to Washington in support of Mitchell’s efforts to locate a veterans’ hospital in Middle Tennessee. The Tennessean described Mitchell as “untiring” in his efforts to push the veterans’ hospital.

Ridley Mitchell overlooked not a single opportunity to curry favor with voters and the Congressman sent a telegram announcing the Federal Land Bank of Louisville, Kentucky “has funds available for loans throughout the Fourth congressional district of Tennessee.” Congressman Mitchell pointed out these loans would be quite helpful to those farmers in need of refinancing or new loans. During the Depression, many farmers did need such loans, badly.

Ridley Mitchell’s keen sense of just what topics might move the public was again demonstrated when he introduced a bill to prohibit members of Congress from hiring their relatives. It was news in Tennessee when Mitchell was informed his bill would get a hearing from a House committee to discuss his bill. Doubtless Ridley Mitchell knew his bill would get nowhere, but after declaring he would continue to pursue the legislation until he was successful, the congressman was well aware it would continue to provide him with much favorable publicity. It would also prove to be an effective tool in his coming campaign against Congressman Ewin L. Davis. During a time when jobs were scarce, especially good jobs, many voters bitterly resented congressmen and senators giving high paying positions to their own kinfolk. Mitchell’s bill resonated with many Tennesseans as well, which is precisely what the congressman intended.

While Ridley Mitchell made the most of his seat in Congress, despite being a freshman legislator, Ewin L. Davis was preoccupied with his chairmanship of the House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries. The committee was not well named, as it also had jurisdiction over radio, an ever-growing enterprise in the country at the time. Davis was carefully charting a course to charge each radio station in the country a licensing fee. While the government needed the additional revenue, it was hardly the sort of topic to move the hearts and minds of the average citizen, nor did many Tennesseans have much interest in the merchant marine. Davis had expressed the opinion advertising took up too much time on the airwaves and intended to “curb too many sales talks” over the radio. While Ewin L. Davis was routinely mentioned in the pages of newspapers across the nation, Ridley Mitchell’s own name was regularly appearing in Tennessee newspapers. A bigger difference was the fact Ridley Mitchell was promoting legislation that appealed to Tennesseans while Ewin L. Davis was working hard on bills of national significance, although perhaps of far less interest to the people of Tennessee. Nor did Ewin L. Davis have Ridley Mitchell’s flair for publicity. Congressman Davis likely knew few, if any, of Ridley Mitchell’s bills would pass Congress, but he miscalculated on the popularity of many of those same measures with Tennesseans. The contest between Ridley Mitchell and Ewin L. Davis came down to that of a “workhorse” congressman against a “show horse” legislator.

While Ridley Mitchell was pushing a new veterans’ hospital for Middle Tennessee, Ewin L. Davis was introducing two bills to eliminate unfair competition from foreign countries in shipping. Davis released a lengthy and mind numbing statement about “foreign vessels”, customs duties, and the like. Doubtless the legislation likely would aid American interests in shipping, but it almost surely seemed far less important to many Tennesseans than the bills being promoted by Ridley Mitchell.

Congressman Mitchell was hardly the only member of the Tennessee Congressional delegation beating the bushes for a new veterans’ hospital to be located in Middle Tennessee; in fact, virtually every member of Congress from Tennessee was working hard for the veterans. The Congressional delegation made a direct appeal to the Veterans’ Bureau, led by Senators Cordell Hull and K. D. McKellar. Senator McKellar detailed the great distance between Johnson City and Memphis, making it difficult for many veterans residing in Middle Tennessee to travel to either location. McKellar also pointed out it was nearly impossible to find beds at either location for those veterans suffering from mental issues, forcing those unfortunates to go to remote places in other states for treatment.

Arguing the need for citing a veterans’ hospital in Tennessee was left to McKellar and the House members, as Hull confined himself largely to introducing the congressmen, after noting he believed the Volunteer State had “the ablest delegation in the House of Representatives.” Even J. Will Taylor, the Republican congressman from East Tennessee, strongly supported locating a new veterans’ hospital in Middle Tennessee.

Congressman Ewin L. Davis did not miss an opportunity to speak out on behalf of his people. Davis, like McKellar, presented a myriad of reasons for the need of a new veterans’ hospital in Middle Tennessee. Congressman Davis pointed to “the rapid growth” of cases requiring treatment. Davis said in 1924 there were 2,160 “mental type cases” in the nine state region, which included Tennessee; by 1931, the number had grown to 3,812. Yet Ridley Mitchell was not to be outdone by his rival.

While Ewin L. Davis had presented an excellent legal brief, Congressman Mitchell “spoke eloquently” on behalf of the veterans of his district. “I am proud to have the honor to represent a people like Judge Lovette (the congressman from Tennessee’s First District) has just described. I know of no man whose distress should be more appealing to us than the man who went through the hardships of war and as a result is dethroned of his reason. It should not be necessary to transport a soldier 500 miles in this condition.” Mitchell went on to paint a pitiful picture of the suffering of “wives, children and other members of a veteran’s family” having to make excruciatingly long trips to see their loved one.

Although still considered the underdog to keep his seat in Congress, Ridley Mitchell appeared to be more than a match for veteran Congressman Ewin L. Davis.