Tennessee had been staunchly for Woodrow Wilson, both in his 1912 campaign for the presidency and his 1916 reelection campaign. Tennessee’s junior United States senator, Kenneth D. McKellar, had been a fervent admirer of President Wilson as a member of the House of Representatives and if anything, his admiration grew as a member of the Senate. McKellar’s senior colleague, John Knight Shields, was able to restrain himself when it came to esteem for the President. McKellar had been the first United States senator elected by the people of Tennessee in 1916; Shields was the last to be elected by the state legislature. In 1918, Shields was running for a second term and had to face the voters, both inside the Democratic primary and the general election. Shields’ lack of fidelity to Woodrow Wilson was to be a factor in his campaign and he was facing a serious challenge for the Democratic nomination from popular governor Tom C. Rye. Governor Rye had not announced his intentions, but possessed an enviable record of achievement, not the least of which had been to unite Tennessee’s Democrats and wrest the governorship away from Republican Ben W. Hooper in 1914.

Rumors seem to have the longest lifespans in politics and churches and Rye had the option of running for a third two-year term for governor or he could run against Senator Shields. By February of 1918, the rumors were circulating that he would forgo an easy reelection race and seek the senatorial nomination. While visiting Knoxville, Governor Rye was queried by a reporter about the Senate race. “I haven’t a thing in the world to say at this time,” Rye replied. There had been intense speculation Rye would announce his candidacy while in Knoxville. Reporters and supporters were equally disappointed.

In early April Governor Rye traveled to Washington, D. C., ostensibly to attend the Americanization Conference. Rye took the time to “look up a number of old friends” while visiting the Capitol. More than likely, Rye was testing the waters for the coming Senate race. The governor kept a hectic pace, traveling all over the state and associated himself with any number of activities relating to supporting America’s soldiers who were fighting in Europe during the First World War. Rye traveled to Huntingdon, Tennessee where the band of John Phillip Souza performed at Thomas’ Park. The governor spoke at the courthouse the same evening on behalf of the Liberty Loan program. By May, Governor Rye was urging Tennesseans to observe “Mother’s Day.” Rye issued a proclamation proclaiming May 12, 1918 “Mother’s Day” in Tennessee. Using the florid language that was popular with the people at the time, Rye reminded Tennesseans, “The tender stroke of a loving mother is more powerful than any scepter, and without her love our armies must be overcome, but en-spirited by its sanctifying memory and influence and emboldened by the thought of defending her from savagery, all things must be and are possible.”

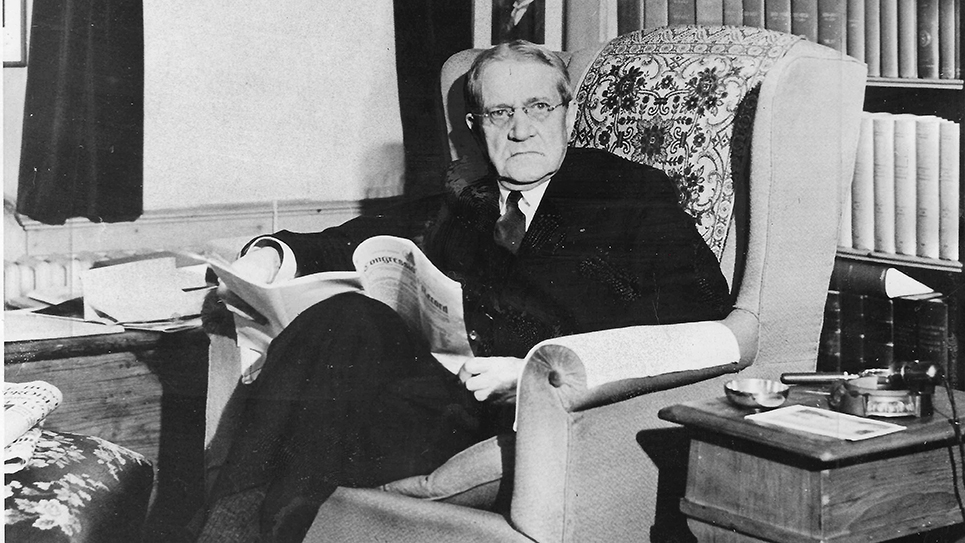

While Governor Tom C. Rye traveled across Tennessee promoting the war effort and blessing motherhood, Senator John Knight Shields largely remained in Washington. In vivid contrast to the affable governor, John Knight Shields was acerbic, gruff, and frequently contrary. A distinguished jurist who had served on the Tennessee State Supreme Court, Shields was not an able politician, nor did he pretend to be. Years later in writing a profile of John Knight Shields for his book “Tennessee Senators As Seen By One of Their Successors,” K. D. McKellar lamented Shields all too often managed to alienate those who should have been his friends. McKellar wrote that patronage was no real benefit to Shields. Senator McKellar readily admitted President Wilson did not like Shields and “did not pay much attention to” those men recommended by Shields for appointment. Shields had a terrific knack for making enemies of people who should have otherwise been grateful to him. Senator Shields, McKellar confessed, was rather “unfortunate” in the way he handled patronage and appointments in Tennessee.

Governor Tom C. Rye, on the other hand, made the most of his own appointive authority, which was plentiful. The governor had numerous jobs and appointments at his disposal and made the most of his opportunities. The rumors he would challenge the curmudgeonly John Knight Shields were still rampant as June approached. The governor was asked while visiting Camden, Tennessee to speak on behalf of the American Red Cross, if “the report” he was off and running for the United States Senate was true. “The report is absolutely untrue and was unauthorized,” Rye snapped.

While Governor Rye’s support for the war effort was undoubtedly good politics, it was also genuine. The governor’s only son, Paul Rye, had enlisted and was commissioned as a Lieutenant. A telegram arrived at the governor’s mansion art the end of May 1918 informing Governor and Mrs. Rye their son had arrived safely overseas. It was always a matter of concern for anxious parents to know their sons arrived safely in Europe due to the perils of constant German submarine warfare. Paul Rye was to serve on the staff of Brigadier General Spence throughout much of the war.

Governor Rye continued his tour on behalf of the Red Cross and spoke in Selmer, Tennessee where he was greeted by a “monster” crowd of local citizens. The Volunteer State spirit of Tennesseans was amply in evidence as even in a small city like Selmer, residents had surpassed the subscription goals for the Red Cross. Rye was the recipient of two pounds of wool sent to him by President Woodrow Wilson from sheep who grazed on the White House lawn. Governor Rye intended to auction off the wool and donate the proceeds to the Red Cross. Wilson’s gift further underscored the President’s cordial relations with the governor and reminding Tennesseans of the chill between Wilson and Senator John Knight Shields. Even before the wool went to the auction block, the governor had received bids totaling $101.

Within days of having denied he was a candidate for the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate, Governor Tom C. Rye announced on May 28, 1918 that he would be a candidate. Declaring he was “yielding to the solicitations of friends and desiring to further serve my people”, Tom C. Rye said he would challenge Senator John Knight Shields for the U. S. Senate. The governor said he did not intend for his campaign to interfere with the wear effort, nor divert attention from the war raging in Europe. Governor Rye said he knew “where the heart of Tennessee is, and should be at this time” and stated he would not make any “unseemly canvass.” Rye also promised that he would not neglect his duties as governor while he sought the senatorial nomination.

Several other prospective senatorial candidates, gauging how difficult it would be to generate support against an incumbent governor and sitting United States senator, decided not to make the race. The senatorial contest came down to Tom C. Rye and John Knight Shields.

Rye made a quick trip to Memphis, receiving friends and supporters in his rooms at the Peabody Hotel. Likely Rye also wanted to discern the attitude of E. H. Crump, leader of the Shelby County political organization, who did not like Senator John Knight Shields. Interviewed by curious reporters, the governor had little to say other than “the outlook was encouraging.” Advertising himself as “The Win The War Candidate”, Rye promised to “stand by our President.” Rye immediately received an endorsement from colorful former governor Malcolm R. Patterson. Despite his checkered past and the fact he was a highly polarizing figure in Tennessee politics, Patterson retained a following among Tennessee Democrats and remained a much sought after speaker.

In this age when candidates announce years in advance of an election, it may be difficult for readers to believe the 1918 Democratic primary campaign for the United States Senate lasted a month. Governor Tom C. Rye kicked off his campaign with a speech at the Lyric Theater in Chattanooga on July 8, 1918. Rye bore down on the record of his opponent, Senator Shields. Rye, supported by former Senator Luke Lea who was also owner of the Nashville Tennessean, castigated Shields for exempting Edward B. Stahlman, a German-American and owner of the rival Nashville Banner, from “the provisions of the enemy alien act.” Rye vigorously disputed what he deemed to be the claims of the newspapers supporting Shields for reelection that President Woodrow Wilson’s call that “politics is adjourned” for the duration of the war, did not mean the senator should run unopposed. Rye lambasted Shields’s attendance record, noting the senior senator had answered 1,652 of 2,070 roll call votes. “Since the beginning of the present session,” Governor Rye cried, “the most important in the history of the country, he was absent on 110 times on roll calls, present and voting 220 times…” Rye scoffed Senator Shields had been more “actively engaged in writing letters to the citizens of the state in the interest of his candidacy, and directing the activities of his hired henchmen in their efforts to organize the state for his election.”

Although Senator Shields remained confident he would carry his native East Tennessee, Tom C. Rye drew a crowd estimated at 1,500 in Kingsport where he was “caustic” in addressing his opponent’s senatorial record. In Lenoir City, the governor filled the high school auditorium and gave an address listeners felt “had the true American ring to it.” Rye moved on to Harriman and received a warm welcome. Governor Rye, asked about his campaign, said he was confident of winning the nomination.

The governor’s campaign released a statement comparing his record with that of Senator John Knight Shields, contrasting Shields’ opposition to organized labor. Rye complained Shields “has endeavored to pose as the friend of labor.” The Rye campaign expressed astonishment that any laboring man could support the senator, pointing to the record Shields had compiled while sitting as a Justice of the Tennessee State Supreme Court. While Rye was pounding hell out of Shields’ record, Luke Lea’s Tennessean gave its endorsement to the governor. Rye had been strongly supported by Lea when he had first sought the governorship in 1914 while the publisher still sat in the United States Senate. Lea had believed helping to elect Rye governor would bolster his own chances of reelection when he faced the people of Tennessee. Lea’s record had been so controversial the State Democratic Committee had called the primary to be held a year before the 1916 election. Lea had been eliminated in the first round of voting, running third behind then-Congressman Kenneth McKellar and former governor Malcolm Patterson. Lea had been bitterly disappointed by Governor Rye’s failure to endorse him. Yet the enmity between John Knight Shields and Luke Lea was too deep for the publisher to back the senator.

The editorial in the Tennessean supporting Tom C. Rye for the United States Senate noted the governor was honest and carried out his campaign promises and would do the same if he was sent to Washington by the voters of Tennessee. The Tennessean also stressed Rye would back “carrying out the policies of the Wilson administration in winning the war for democracy and civilization” if elected. Lea’s newspaper denounced Senator John Knight Shields’ record as a “twisted and insincere performance” which had been “governed by expediency and controlled by self interest as against public interest.” The Tennessean thundered Shields had “shamefully and shamelessly perverted a public trust, and this is the only thing he has done consistently since he has been Senator.” The Tennessean snarled Senator Shields “keeps faith with no man or constituency unless it serves his own personal ambition, or selfish interest to do so.” Lea accused Shields of making “an unholy alliance” with Jesse Littleton of Chattanooga, Tennessee’s Republican National Committeeman, in order to gain the support of Littleton’s political organization inside the Third Congressional District.

It was clear to most, if one supported Woodrow Wilson, one must support Governor Tom C. Rye.