By Ray Hill

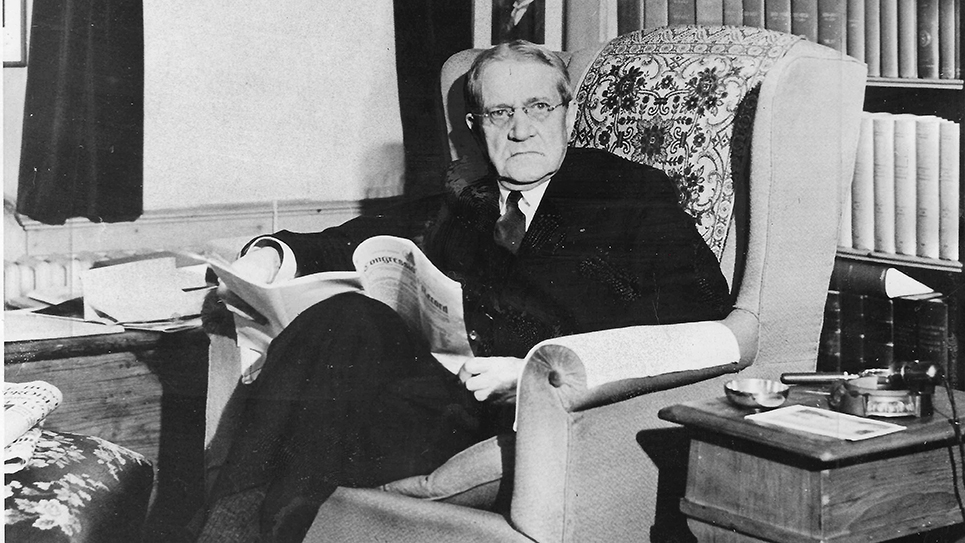

Few men have lived as colorful and productive a life as did William Gibbs McAdoo, who was, incidentally, a one-time resident of Knoxville. A lawyer, businessman, son-in-law of a President of the United States, member of a President’s Cabinet, U.S. Senator from California, and presidential aspirant, W. G. McAdoo left little undone in his lifetime.

McAdoo was born on October 31, 1863 in Marietta, Georgia. The McAdoo family was an accomplished one, as his father was an attorney and his mother was an author, while an uncle was a Justice of the Texas Supreme Court. In 1877, the McAdoo family relocated to Knoxville, where the elder McAdoo had accepted a position as a professor at the University of Tennessee. The younger McAdoo himself graduated from UT and went on to serve as deputy clerk for the U. S. District Court for East Tennessee. McAdoo married for the first time in 1885 to Sarah Fleming and that union produced no less than seven children. 1885 was also the year McAdoo commenced his own law practice, although he moved from Knoxville to Chattanooga to engage in his new profession.

For his time, W. G. McAdoo was certainly an entrepreneur and he was constantly working on various projects to make himself rich. McAdoo lost whatever money he had when he made an unsuccessful attempt to electrify the Knoxville street transit system. After that spectacular failure, McAdoo moved yet again, this time to New York City where he joined with the son of a former Confederate general in selling securities. By 1895 McAdoo was back in Knoxville where he managed to regain control of his streetcar company, which had been bankrupt and auctioned off. McAdoo was soon engaged in a dispute with another businessman, C. C. Howell, over Knoxville’s streetcar system. Ultimately, that dispute led to an actual riot known as the “Battle of Depot Street”, leaving one citizen dead and numerous others injured in the resulting melee. City of Knoxville and Knox County officials had sided with either Howell or McAdoo and the police officer’s clashed with Sheriff’s deputies and just about everybody was arrested by somebody, not the least of which was the Mayor and Chief of Police.

Ultimately, the courts decided in favor of C. C. Howell and a disgusted McAdoo retreated from Knoxville and returned to New York and the practice of law. It was not long before McAdoo had another project on his mind; he assumed the presidency of the Hudson and Manhattan Railway Company and proposed to build a tunnel beneath the Hudson River to connect New York City to New Jersey. Eventually, the tunnel was built and still operates today.

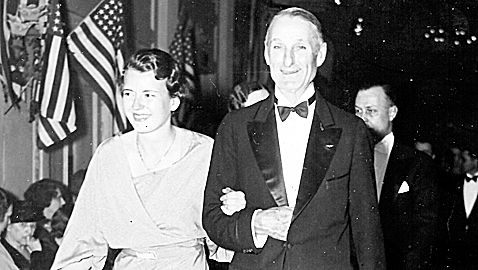

In 1912 McAdoo worked hard on behalf of New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson’s presidential campaign. It was also the same year McAdoo’s wife, Sarah, died. Wilson was grateful to McAdoo for his support and named him as Secretary of the Treasury. McAdoo was soon courting President Wilson’s daughter Eleanor and the two were married in a ceremony held at the White House in 1914. The groom was then fifty-one years old and the bride a mere twenty-five and McAdoo offered to resign from the Cabinet, but Wilson demurred. McAdoo and his new wife soon produced two daughters and he remained a member of Woodrow Wilson’s Cabinet until his resignation in 1918.

McAdoo resumed his law practice after departing Wilson’s Cabinet and was a very successful attorney. McAdoo was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination at the 1920 convention, despite the fact Woodrow Wilson wanted a third term. Wilson, severely incapacitated by a stroke, was bitterly disappointed by his failure to be renominated by his party and McAdoo led on the first ballot, but lost the nomination to Ohio Governor James Cox. Americans were tired of Wilson and his administration and the Republicans won a landslide victory, capturing both houses of Congress, as well as the presidency.

In 1922, McAdoo left New York to establish a new law firm in Los Angeles, California. McAdoo also owned an estate in Santa Barbara, California where he grew avocadoes. Attorney McAdoo quickly acquired several prestigious clients, including movie studios. One of his clients led to an embarrassing incident, which damaged McAdoo’s presidential ambitions. McAdoo had accepted a retainer of $25,000 from oil baron Edward Doheny, unaware of Doheny’s having given substantial sums to Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall. The Interior Secretary also just happened to be turning over oil reserves to Doheny, leading to the Teapot Dome scandal, which did much to damage the Harding Administration and eventually led to Fall’s conviction and imprisonment. McAdoo had returned Doheny’s retainer, but not before being himself tainted in the resulting scandal.

McAdoo was again a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1924. McAdoo won several primary contests and was a strong prohibitionist, while his chief rival, New York Governor Alfred E. Smith, was an equally strong “wet” or anti-prohibitionist. The rivalry between McAdoo and Smith was so intense it deadlocked the convention and after 103 ballots, Democrats nominated attorney John W. Davis who was crushed by Republican President Calvin Coolidge.

W. G. McAdoo was reluctant to enter the presidential contest in 1928 and was none to happy to see his old nemesis Alfred E. Smith get the nomination. Smith’s Catholicism broke the solidly Democratic South and states like Tennessee, Texas, North Carolina, Virginia and Florida fell into the Republican column.

The Great Depression and the terminal unpopularity of President Herbert Hoover gave hope to Democrats of recapturing the presidency and William Gibbs McAdoo himself entertained some hopes of perhaps being the presidential nominee. McAdoo was Chairman of the California delegation to the Democratic National Convention and the shrewd old campaigner watched New York Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt struggle to achieve the two-thirds vote required by party rules to gain the nomination. The California primary had been won by Speaker of the House John Nance Garner who had the support of press lord William Randolph Hearst and the delegation from California was ostensibly supporting the Speaker. McAdoo thought if another deadlock occurred, lightning might strike and he could emerge as the nominee and just about any Democrat could beat Hoover, a notion Alfred E. Smith shared.

Speaker Garner eventually released his delegates and McAdoo, sensing Texas was about to break, scurried down to the podium to seek recognition. Once recognized, McAdoo seized the moment and declared all of California’s votes had gone to FDR, giving Roosevelt the presidential nomination. Roosevelt, listening to the proceedings on the radio, smiled and exclaimed, “Good old McAdoo!” McAdoo assuaged his unrequited ambition to be the presidential candidate by becoming the Democratic nominee for the United States Senate. The incumbent, Samuel Shortridge, had been defeated in the primary and despite a Republican advantage in voter registration, McAdoo defeated both the Republican and Prohibitionist candidates to win the election.

W. G. McAdoo was not a power in the United States Senate, but he was a power in California. McAdoo constantly badgered the Roosevelt administration about Federal patronage and he kept such a tight reign on appointments that it caused friction among feuding California Democrats. McAdoo and more conservative California Democrats were appalled by the rise of author Upton Sinclair who won the nomination for governor in 1934 with a scheme for ending poverty in California. The “EPIC” movement swept the primaries and McAdoo had absented himself from California and regular Democrats deserted Sinclair in droves and the Republican governor was easily reelected.

McAdoo did little to help himself when it was announced he and Eleanor Wilson McAdoo were getting a divorce in 1934. Mrs. McAdoo explained she could no longer bear the climate in the nation’s Capitol and preferred living in California year round for health reasons. The seventy-one year old McAdoo’s remarriage just a month after his divorce from the dead Woodrow Wilson’s daughter to a twenty-six year old nurse raised more than a few eyebrows.

EPIC Democrats did not forgive Senator McAdoo and in 1938 he faced Sheridan Downey, an EPIC Democrat who had embraced the Townsend Plan, which would pay the elderly a $200 per month pension, provided seniors spent all the money every month. McAdoo was frantic to have the open support of the highly popular President Roosevelt in his primary campaign. Roosevelt had endorsed several Democrats across the country, still smolderingly angry with many senators who had failed to support his plan to enlarge the U. S. Supreme Court. McAdoo got Roosevelt’s endorsement and like many others who got the nod from the President, lost anyway.

W. G. McAdoo was bitterly disappointed by his failure to win renomination and resigned from his Senate seat early to accept the presidency of the American Steamship Lines.

McAdoo pointed to the vulnerability of Pearl Harbor well before the Japanese attacked the naval facility in 1941. The former senator also tried hard to keep his influence in appointments and Federal patronage matters in California, despite dividing his time between California, New York and Washington, D. C. McAdoo kept up a frenetic pace, especially for a seventy-seven year old man. It proved too much for him and McAdoo suffered a heart attack while at his apartment in Washington’s Shoreham Hotel. McAdoo suffered another heart seizure, which proved to be fatal on February 1, 1941.

William Gibbs McAdoo’s much younger wife, Doris Cross McAdoo, apparently never remarried and outlived the former senator by more than fifty years. McAdoo had become a wealthy man by the time of his death and had participated in some of the most momentous times in American history.