By Ray Hill

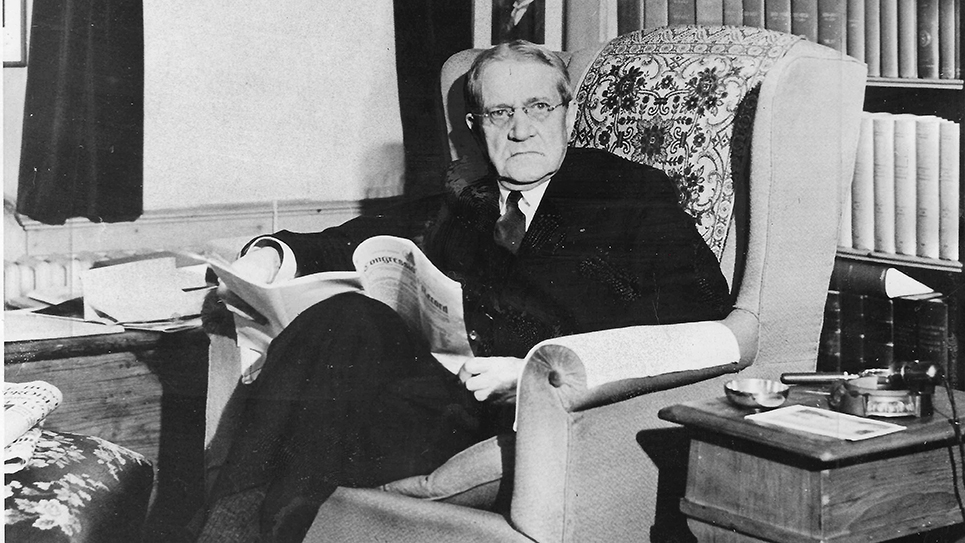

Following Congressman J. Will Taylor’s death from an unexpected heart attack on November 14, 1939 there was an outpouring of grief on the part of the people of Tennessee’s Second Congressional district. Taylor had long been a power in Tennessee and during the administrations of Presidents Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover, had been the Republican “boss” of the state. It was J. Will Taylor who dispensed most of the federal patronage and appointments in Tennessee during the twelve years of national Republican rule. Taylor remained highly popular inside his own district and reached accommodations with powerful Democrats like Senator Kenneth D. McKellar, which proved to be helpful once Franklin D. Roosevelt came to power in 1933. The root of J. Will Taylor’s popularity inside his own district came down to the congressman’s industry and indefatigable energy in doing things for his people, a fact “Uncle” Bob Smith, the custodian of the Federal Building in Knoxville and a Democrat, readily admitted. Smith said he never knew “a man who was as quick to do a favor for another as J. Will Taylor.”

Like many others inside Tennessee’s Second Congressional district, “Uncle” Bob Smith had his own personal story to tell. “I was discharged from the regular army in the Philippines many years ago for heart trouble and general disability,” Smith said. “I tried through various others for 10 years to get a pension and made no headway. Then I told Bill Taylor about it. We were on opposite sides of the fence but he got that pension for me in 30 days.”

Nor was that the only time J. Will Taylor helped “Uncle” Bob Smith. The custodian told a News-Sentinel reporter, “Recently I lost my discharge from the Army. I told Congressman Taylor about it. He obtained a duplicate from Washington for me within 10 days. That was six weeks ago.”

Will Taylor had represented the district since his election in 1918. Tributes to the late congressman poured in from colleagues, but perhaps the most interesting observations came from those who had encountered Taylor in other circumstances.

James Wallace, a janitor and elevator operator in the Post Office building knew “Hillbilly Bill” for eighteen years. Wallace readily shared his impressions of the late Congressman.

“Congressman Taylor was never too busy to talk to the lowliest man here about any personal problem, and help however he could,” Wallace said. “When I told him sometime ago that I was planning to buy a little place of my own he said that was a wonderful idea. He went with me two or three times to look at places. And when I finally decided on one Mr. Taylor talked to the owner and helped work out terms that I could meet.”

A reporter for the Knoxville News-Sentinel recalled Congressman Taylor’s persistence in finding a job for a friend. The future reporter was then attending George Washington University in Washington, D. C. and stopped by Taylor’s office and wondered if the congressman could help him find a part-time work. J. Will Taylor put the young man in his car and the reporter recalled they “sailed from one private office building to another.” Eventually, Taylor helped his young friend get a job with Southern Railway that the reporter remembered helped to pay for much of his college education. Nor did Congressman Taylor leave it at that; if Taylor hadn’t seen his young friend often enough, he would telephone the young man to inquire if he was all right and doing well.

The local manager for the Knoxville Chamber of Commerce, Fred Roberts, fondly recalled his late friend J. Will Taylor. Having known Taylor before he was first elected to Congress, the two had long exchanged “Dear Bill” and “Dear Fred” letters. Roberts remembered when he took a delegation of Knoxvillians to Washington, although he acknowledged they held little hope for successfully pushing their own particular project, which even Roberts described as “a pretty forlorn hope.” Roberts said the delegation had not been successful in their efforts when they ran into Congressman Taylor, who promptly asked, “What are you hill-billies doing up here?”

Once the delegation informed Taylor of their mission, he simply said, “Come on.”

Roberts marveled, “Closed doors didn’t mean anything to Bill. He went on in and around the secretaries until he got the delegation to the man they wanted to see. The results weren’t 100% successful, but they were a lot better than anybody expected before Bill took charge of the delegation.”

Fred Roberts also related how he had asked Congressman Taylor to testify before the Civil Aeronautics Authority on behalf of Knoxville getting additional airlines. “No letters got prompter answers than those to Bill Taylor and it’s the same with Senator McKellar,” Roberts said.

Taylor’s sudden passing was all the more shocking as he had been in his Knoxville office in the Federal Building the day he died. Assistant Postmaster E. O. Beeler said, “He came in jolly as ever.” The Congressman arrived with “a pile of baggage” Beeler recalled “and we got a man to help him upstairs with it.” Beeler said Taylor appeared to be in good health and noted the congressman “didn’t complain any.”

Yet Lieutenant I. F. Griffin of the Navy Recruiting office had a different opinion. Seeing Congressman Taylor that same day, he thought “Hillbilly Bill” looked ill. “When Mr. Taylor came down the hall to his door, he was breathing awfully rapidly, more so than usual,” Griffin remembered.

Ill or in the best of health, J. Will Taylor was only fifty-nine years old when he died. Taylor left his widow and two daughters, Elizabeth and Katherine. The Congressman’s office in Knoxville remained in the same condition he left it; much of Taylor’s baggage was scattered about his personal office. A typewriter remained partially unpacked on the congressman’s desk. Unopened letters were strewn around his personal office, along with the clothes J. Will Taylor brought back from the special session of Congress. Taylor had friends everywhere, high and low. Friends from two of his favorite destinations in Knoxville, the Farragut Hotel and Weaver’s Restaurant, were especially fond of “Hillbilly Bill.” Alton Cureton, the Bell Captain at the Farragut Hotel said “us boys as much as anybody” would miss the congressman. “It was a pleasure to serve Mr. Taylor,” Cureton said. “He knew the boys by name and he shook hands with us just as quick as anybody. He was an all-year man too – – – not only just before election time.” Taylor, “a big fellow”, liked his food and enjoyed “a big country breakfast” each morning. Congressman Taylor usually dined on “fruit, cereal, country ham and eggs” of a morning. Restaurateur Frank Weaver remembered the congressman coming into his restaurant, usually accompanied by three or four others, for supper. “He often liked a steak then, and he was especially fond of frog legs,” Weaver said. Weaver had been impressed by J. Will Taylor’s friendliness, recalling the congressman usually knew most everyone in the restaurant, but if he saw a stranger, “Hillbilly Bill” made himself acquainted. “He greeted everybody the same – – – Democrat or Republican, white or black,” Frank Weaver said.

Shortly after Congressman J. Will Taylor’s death, a mystery developed over his office. Taylor’s daughter Elizabeth hired an attorney and was anxious to be admitted to her late father’s Washington office “without being observed by a large group of reporters, photographers and curiosity-seekers” who had foiled one previous attempt. The regulations surrounding the office of a member who had died were quite clear; the office was to remain open and was to be run by the congressman or senator’s secretary or Chief of Staff. In the case of Congressman J. Will Taylor, his chief secretary was Miss Dorothy Schultz. Elizabeth Taylor made it quite clear she wanted to go through her late father’s office and personal effects “alone.” Miss Schultz, described by a Knoxville News-Sentinel reporter as “an attractive red-haired woman”, had been Taylor’s secretary for twenty-one years. When asked whether or not Miss Schultz would be allowed entry into the dead congressman’s office, Miss Taylor’s attorney snapped, “We don’t know anything about Miss Schultz or her affairs.” It was a mighty peculiar reply involving a woman who had worked for J. Will Taylor for twenty-one years. It seems hardly possible neither the congressman’s widow or daughters would not be well acquainted with Miss Schultz. Even more odd was Elizabeth Taylor’s demand that a Capitol policeman stand guard outside the door of her father’s Washington office. As curious reporters and photographers began to gather, Miss Taylor retreated to the office of Congressman Walter Chandler, which was next door to that of J. Will Taylor. There was no indication by Elizabeth Taylor as to just when Miss Schultz could enter the office, as it was customary for a congressional secretary be allowed twenty days to begin gathering up the deceased incumbents papers before being assigned to a temporary office. Prime office space was reserved for living congressmen. Congress had also included in its rules that the staff of a congressman who either died in office or resigned was to be carried on the payroll at full salary for six months or until a successor was duly elected. The staff was to be supervised by the Clerk of the House. Congressman J. Will Taylor had a staff of two and divided his staff between Washington and his Knoxville office. Miss Schultz was Taylor’s secretary in Washington, D. C. while Robert Davis held the same duties in the Knoxville office. Each congressman was given an allowance of $416.66 per month, which he or she could divide between employees as he or she wished; the only stipulation was no assistant could be paid more than $325 monthly. Dorothy Schultz had been paid $321.66 per month, while Robert Davis earned $95 monthly. It was not an unusual practice at the time for congressman to pay the secretary the lion’s share of the allowance and paying the clerk far less.

Taylor’s younger daughter, Katherine, was engaged in the far more pleasant pastime of thanking Tennesseans for their condolences on the death of her father. “We wish to express our sincere appreciation to our friends for the many expressions of sympathy and acts of kindness shown us during our recent bereavement,” Miss Taylor said in a statement, which she telephoned to the News-Sentinel.

Elizabeth Taylor’s attempts to get into her father’s Washington office were finally successful and the officer standing guard was allowed to do something more productive. John Moutoux, the Knoxville News-Sentinel’s Washington correspondent, reported Miss Taylor and a friend from the late congressman’s home city of LaFollette, Mrs. R. J. Buckman, were busily boxing up papers “of a private nature” to take home to Tennessee. Dorothy Schultz sorted through the remaining papers, which were to be removed to an office on the fifth floor of the House Office Building.

The mystery would only grow deeper.