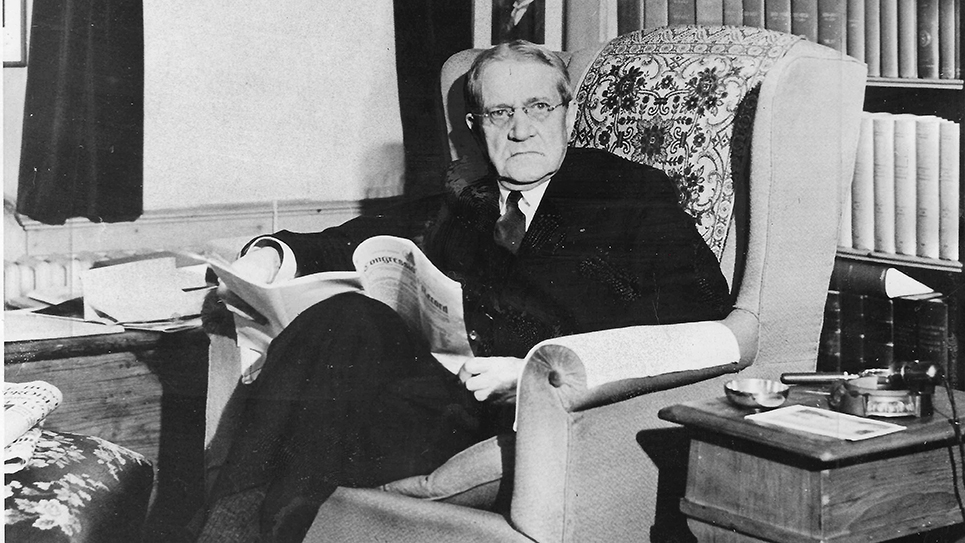

When Congressman J. Will Taylor died on November 14, 1939, it sent shock waves through Tennessee’s political community. Taylor had long been enormously popular inside Tennessee’s Second Congressional district and “Hillbilly Bill” had exercised considerable influence throughout the state, especially when the GOP dominated the White House. Taylor’s influence lessened somewhat with the election of Franklin Roosevelt as president, but the wily congressman was a shrewd politician and he reached an understanding of sorts with Tennessee’s leading Democrats, not the least of which was Senator K. D. McKellar.

The Taylor family had insisted a guard be placed outside the Washington office of the late Congressman J. Will Taylor. The request was supposedly made by the congressman’s widow; evidently Mrs. Taylor had personally telephoned Kenneth Romney, the House Sergeant-At-Arms to ask for around-the-clock guards to be stationed outside her dead husband’s office. Mr. Romney was sick in bed when contacted by a reporter, but Mrs. Romney helpfully explained the situation. “Mr. Romney had a long distance telephone call from Mrs. Taylor Tuesday night,” Mrs. Romney recalled. “Mrs. Taylor asked that no one be permitted to go into Mr. Taylor’s office. He (Mr. Romney) doesn’t know anything more than that. The guard will remain there until an executor arrives. She didn’t say when that would be.”

No official of the U. S. House of Representatives could ever remember any similar case previously and the request of the widow Taylor was all the more puzzling as the only people who had keys to the Washington office, aside from the Taylor family, were the late congressman’s staff members. As Mrs. Taylor was ill, her daughter Elizabeth was designated to make the trip to Washington. “I will go to Washington as her agent, within a few days,” Miss Taylor announced.

The notion Mrs. Taylor’s request was “customary” was seconded by Dorothy Schultz, J. Will Taylor’s secretary for twenty-one years. Miss Schultz said she was preparing to leave Knoxville for Washington, D. C. at the request of Elizabeth Taylor. “I see nothing unusual about that police order,” Miss Schultz said coolly. “It is the customary thing.”

“The sergeant at arms when here told us that it was customary to seal the office until the executor arrives.” Elizabeth Taylor claimed not to know any other reason for posting a guard outside her father’s office. Three Capitol policemen rotated eight-hour shifts sitting in a chair outside the door to J. Will Taylor’s office.

Elizabeth Taylor, one of the late congressman’s two daughters had hurried to Washington, D. C. seeking access to her father’s office. The late congressman’s personal secretary, Dorothy Schultz, had been kept out of the office until Miss Taylor could go through her father’s personal effects. Miss Taylor, accompanied by her attorney, managed to finally get inside her father’s office on a Saturday night. On Sunday, Miss Taylor, joined by Mrs. R. J. Buckman and Dorothy Schultz, returned to the office to complete packing up Congressman Taylor’s papers. Mrs. Buckman was a personal friend of Miss Taylor’s and the two had driven up to Washington, D. C. together from the Taylor family home in LaFollette.

Miss Schultz worked alongside Miss Taylor and Mrs. Buckman, although the congressman’s daughter locked the doors to the office. When pressed as to why there was a need to post a guard outside J. Will Taylor’s Washington office, his daughter replied, “The seal of the Knoxville office had been broken into, so we telephoned Mr. Romney (the House Sergeant-At-Arms) and asked him to see to it that no one got into the office here until someone from the family had a chance to reach Washington. We did not ask for guards but presumably that was Mr. Romney’s way of carrying out our request.”

Miss Taylor’s reference to the seal being broken was a piece of tape placed across the door of J. Will Taylor’s Knoxville office on the third floor of the Federal Building. When Miss Taylor had first visited her father’s Knoxville office, she had been joined by Sheriff Carroll Cate and Knox County Welfare Commissioner I. C. King, both close friends of her late father. King had served as U. S. Marshall throughout much of the decades of the 1920s through the recommendation of Congressman J. Will Taylor. There is still a park in Knox County named for I. C. King.

The tape covering the keyhole to Congressman Taylor’s office had been broken, causing Elizabeth Taylor to become concerned. “The tape was broken,” Sheriff Cate admitted, “but there is no way of telling whether the door was actually opened or if so whether anything was taken.” I. C. King was far less communicative than Sheriff Cate, replying when queried that he had “nothing to say” about the matter.

The local postmaster, Woodruff Booth said, “The paper tape was placed on the door which was locked. Whoever went in the office used a key.” Booth added, “There won’t be any investigation unless the Taylor family asks for one.”

While Elizabeth Taylor had been preoccupied in Washington, D. C., her sister Katherine had been busy cleaning out her father’s Knoxville office. Local Republicans were less interested in the Taylor daughters’ efforts to recover their father’s papers than who would succeed the veteran congressman. For a time, Elizabeth Taylor pondered becoming a candidate. It was not unheard of for the widows of congressmen to be nominated and elected to serve out the remainder of their husbands’ terms. A few decades later exactly that would happen in Tennessee’s Second Congressional district when GOP leaders prevailed upon Irene Baker, the widow of Howard Baker, Sr., to become a candidate. The appeal of a congressional widow running was that it was difficult for a challenger to mount a successful campaign due to the usual sympathy for the wife of a dead man. It also prevented bloody and hard fought primaries, as well as giving prospective candidates the opportunity to strengthen their respective bases and prepare for a campaign in a regular election year.

A candidacy by Elizabeth Taylor, a thirty-two year old schoolteacher, might help avoid a divisive battle among East Tennessee Republicans. While the Second District was solidly Republican and had never elected anything but a Republican to represent it in Congress since the GOP first appeared on the ballot, Republicans had been shaken when J. Will Taylor almost lost reelection in 1936. That had been a banner year for Democrats as President Franklin D. Roosevelt was coasting to reelection, winning every state in the nation save for Vermont and Maine. Taylor also faced a formidable candidate, John J. O’Connor, the mayor of Knoxville. Congressman Taylor, after eighteen years in office, only won by 1,604 votes. Taylor had won reelection in 1932, another big year for Democrats, with almost 58% of the vote. In 1936, Taylor’s margin had declined to just over 50%. While Taylor had been reelected handsomely in 1938, many Republicans inside the Second Congressional district worried a divisive contest inside the party would only help the Democrats who were intent upon running another serious candidate in the special election to fill the vacancy caused by J. Will Taylor’s death. Another sign the Democrats were pondering a serious challenge to Republican hegemony was the speculation Burgin Dossett might become a candidate for Congress. Dossett had lost a race for governor in the Democratic primary to Gordon Browning in 1936, but was believed to be a popular figure in the Second Congressional district.

Days after her father’s death a modest boom began for Elizabeth Taylor. At least one other prospective candidate, Jack Dance, said he would not make a final decision until Miss Taylor made up her own mind. “Until she decides about filling his seat, I am not a candidate.” Dance had twice successfully managed J. Will Taylor’s congressional races. Dance was careful to say, “And I think it would be a grand tribute to a great Tennessean to pay his family this respect.” Jack Dance acknowledged there was some support for Elizabeth Taylor to succeed her father, although he very well may exaggerated it. “I find there is a sentiment over the Second District for Miss Taylor to fill out the unexpired term of her father.”

Judge Hu B. Webster, a local power in the Knox County Republican party, said he believed either J. Will Taylor’s widow or daughter ought to be selected to fill the seat until a successor could run in the regular election in 1940. Webster thought it unseemly for other candidates to express interest in running for Congress before Mrs. Taylor or Elizabeth Taylor made up their minds whether or not they wished to be candidates in the special election.

Beecher Witt, attorney general for Madisonville, readily expressed an interest in running for Congress, but was cautious about a possible Elizabeth Taylor candidacy. “I would withhold my candidacy if Miss Taylor wishes to become a candidate,” Witt said. “I want to do what’s proper and in accord with the Republicans of the district and I think the idea of Miss Taylor filling out the unexpired term without opposition from Republicans is a fine thing.”

The Clinton Courier lamented after surveying the possible candidates to succeed Congressman Taylor it appeared to be “just about the hungriest bunch of politicians we’ve even seen listed together” with “the notable exception of Miss Elizabeth Taylor.” The Courier complained it could quite nearly hear those same hungry politicians “licking their chops” in anticipation.

Hometown folks in LaFollette seemed genuinely interested in Miss Taylor running in the special election to fill her father’s seat and some thought it would be “a fine tribute” to the late congressman to allow his daughter to serve a brief term in the House of Representatives. State Senator W. A. W. Carden, who had known Elizabeth Taylor since her birth, claimed the congressman’s daughter had “inherited traits of her distinguished father and has the ability to carry on his unfinished work.” Carden’s endorsement may have been more harmful to Elizabeth Taylor’s prospective candidacy than helpful. Opposition began to gather to the idea of Miss Taylor succeeding her father, even briefly. One prominent Republican growled that allowing Elizabeth Taylor to serve in Congress would mean Wheeler Carden would likely become the “Congressman without portfolio.” Other powerful Republicans objected to the idea of honoring Miss Taylor and believed it was better to nominate and elect a Republican who could immediately begin to garner seniority and be reelected in 1940.

Elizabeth Taylor flirted with the idea of becoming a candidate to succeed her father, although there was not an outpouring of support for her. When Miss Taylor eventually announced she would not become a candidate to succeed her father, the Memphis Press Scimitar published an editorial hailing her decision titled “Inheriting Public Jobs.” As indicated by the headline, the editorial was far from complimentary, noting “we are glad she will not become a candidate at this time.” The Press Scimitar archly said, “If she feels that her abilities and talents can better serve our state in the halls of Congress than in the schoolroom, we should be very glad to see her exercise her right and offer herself for such service at some other date, when the voters can judge her and her platform uninfluenced by maudlin sentimentalism.”

In the end, Miss Taylor, citing the ill health of her mother, decided not to run. Republicans held a tumultuous convention, which nominated Judge John Jennings, who had once been soundly defeated in a primary by J. Will Taylor. Once nominated, Jennings won the general election and served in Congress until his defeat in 1950 by Howard Baker, Sr. The mystery of who, if anyone, had broken into “Hillbilly Bill’s” office remains to this day.