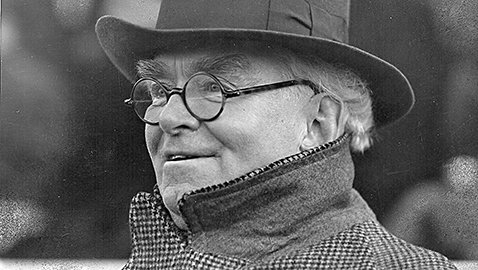

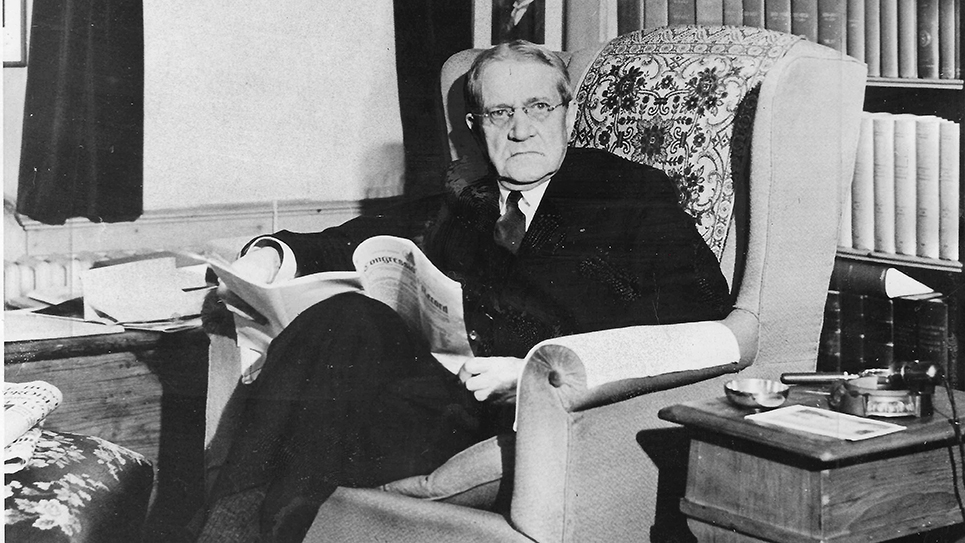

Edward H. Crump, leader of the Shelby County political machine, had decided to go to Congress in 1930. The incumbent, Hubert Fisher, had not been ready to retire despite the fact he was quite nearly entirely deaf. Relations between Crump and his long-time friend Senator Kenneth McKellar were strained as the Memphis Boss navigated official Washington. McKellar was one of the more senior Democrats in the Senate and a real power in Washington, D. C. Crump was a junior congressman without any real influence outside Shelby County. Crump was likely jealous of the prestige and power McKellar commanded in the nation’s Capitol and resented the fact the senator had done little or nothing to impeach Governor Henry Horton. McKellar had been reportedly irritated by Crump’s callous treatment of Hubert Fisher in unceremoniously dumping the congressman. Personal relations between the two continued to deteriorate over the next year.

Crump backed Memphis mayor Watkins Overton in a bid to be elected as a delegate-at-large to the 1932 Democratic National convention perhaps in the belief Overton’s candidacy might forestall that of McKellar. If so, the Memphis Boss was disappointed as Senator McKellar publicly announced his own candidacy for a delegate-at-large seat on March 25, 1932. Crump admitted he had not been consulted prior to McKellar’s announcement. Senator McKellar clearly had no intention of seeking Crump’s blessing before declaring he would be a candidate. Both Crump and McKellar knew the Boss’s influence was confined to Shelby County, while the senator commanded an organization that ranged from the eastern most part of the state to Memphis, which was also McKellar’s home. Crump realized that in a show down with McKellar, he would likely be the loser. McKellar was extraordinarily personally popular with most Tennessee Democrats and had been effective in the U. S. Senate.

Obviously, Watkins Overton did not command the kind of allegiance and respect from Tennessee Democrats that K. D. McKellar did. The Nashville Tennessean, owned by Luke Lea, chortled McKellar’s candidacy was a direct “challenge” to Crump’s authority. The political reporter for the Tennessean speculated should the fight continue all the way to the ballot box, Senator McKellar could easily “double the vote cast for Mayor Watkins Overton…”

McKellar’s announcement he would seek one of the delegate-at-large positions at the Democratic National Convention was followed by a statement from Tennessee’s junior U. S. senator, Cordell Hull. Senator Hull said he, too, would run for a seat as a delegate-at-large. Both McKellar and Hull, as well as every member of the Tennessee Congressional delegation, was present to discuss the need for “proper hospital facilities in Middle Tennessee” for veterans of the World War. The only congressman absent from the meeting was E. H. Crump.

Congressman Crump introduced his first bill on April 8, 1932, a year after having been sworn into the House of Representatives. Crump’s bill sought $3 million for “special public health services and studies and demonstration work in rural sanitation.” Crump hastily dropped his congressional work to return to Memphis when his elderly mother was hospitalized for a major operation. The rumors of the break with Senator McKellar continued to waft all across Tennessee as Crump was reportedly considering backing a comeback bid by former governor Malcolm Patterson. Patterson, then a judge in Shelby County, had been one of the most polarizing figures in Tennessee’s long political history. Patterson’s pardoning of the late senator Edward W. Carmack’s killers had forced him out of the governor’s office. Patterson tried to get himself elected to the United States Senate and had lost to K. D. McKellar in 1915. Patterson announced he would seek the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in April of 1932 and while his announcement was greeted with silence by Crump, some believed the Memphis Boss was inclined to support his former foe. McKellar was openly supporting the candidacy of former State Treasurer Hill McAlister, once again seemingly putting the senator at odds with Crump. Congressman Crump issued a terse statement, indicating he would “say something before I leave for Washington again, which will be soon.”

Patterson quickly received the support of Luke Lea and the Horton administration, making it very unlikely Ed Crump would back him. Crump quickly realized the situation would allow Senator McKellar to ally himself with machine opponents. When McKellar was selected to keynote the 1932 Tennessee Democratic convention, the Memphis Commercial Appeal, friendly to Crump, said McKellar’s selection would give Crump supporters “plenty to worry about.” The Commercial Appeal noted relations between Senator McKellar and Crump had gone from an attitude of “coolness” to positive “frigidity” and stated there had been no contact between the two men since Crump went to Congress.

Crump’s chief lieutenant, Frank “Roxie” Rice, not surprisingly issued an announcement in May 1932 the rift between Senator McKellar and Congressman Crump was “healing.” Rice had made a visit to Washington and said, “Senator McKellar, Mr. Crump and myself had a very friendly luncheon together.” The machine followed Rice’s statement with a public declaration Shelby County would heartily endorse McKellar’s election as a delegate-at-large to the Democratic National Convention. McKellar and Memphis mayor Watkins Overton were endorsed to serve as delegates-at-large, while Crump was selected as a delegate from Shelby County. At least on the surface, the Shelby County gathering was completely harmonious. Crump, usually a highly practical politician, realized there was nothing he could do to prevent McKellar from being named a delegate-at-large. The Memphis Boss quickly concluded feuding with the powerful senator would do nothing to improve his political situation in either Shelby County or Tennessee.

By the time of the state convention Senator McKellar was ill and Congressman Gordon Browning made the keynote speech instead. With McKellar, Cordell Hull and Crump all announced as being strongly in favor of the nomination of Franklin D. Roosevelt as the candidate of the Democratic Party, all twenty-four of Tennessee’s delegates to the national convention were pledged to support the New York governor. Another sign of the improving relations between McKellar and Crump were the strong rumors the Memphis Boss was moving behind the gubernatorial candidacy of Hill McAlister, a favorite of the senator. Evidently the rumors had some validity as Malcolm Patterson, speaking in Memphis, railed against McAlister as twice the recipient of the “fraudulent negro vote of Shelby County…” Congressman Crump retorted the former governor was “trying hard to divert the public mind from his corrupt backing by jumping on me.” As former governor Malcolm Patterson celebrated his seventy-first birthday Crump joined his ally Senator McKellar and announced his support for Hill McAlister for the gubernatorial nomination.

As Crump headed off to Chicago to attend the Democratic National Convention, the Tennessean complained there were “26,000 Negroes registered to vote for the Crump machine” in Shelby County. Crump was running for reelection to Congress, although it was abundantly clear he was less interested in national issues than state and local matters. Crump also disliked being in Washington, much preferring his home on Peabody Avenue in Memphis. Unlike the bachelor Senator McKellar, who lived in hotels in Washington and Memphis, Crump enjoyed the company of his wife and sons. Nor did Crump especially enjoy being the whipping boy of the Patterson campaign. Newspapers ads all across Tennessee proclaimed “A Vote For Patterson Is A Vote Against Crump.” The aging former governor enjoyed the all out support of the Horton administration and Luke Lea’s Nashville Tennessean. The Tennessean heralded Patterson had drawn a “record crowd” in Bolivar, Tennessee when he spoke there. According to the Tennessean, Hugh Williams, editor of the Bolivar Bulletin, estimated some 1,800 people came to the courthouse to hear the former governor speak. Patterson charged that Crump was attempting to gain control of the state through the candidacy of Hill McAlister. Nor did Patterson ignore the local machine in Davidson County headed by Mayor Hilary Howse, which was also backing McAlister. Patterson took less notice of the third candidate competing for the gubernatorial nomination, Lewis Pope, who had served in the administration of several Tennessee governors. When Patterson spoke in Somerville, Tennessee, the Tennessean once again claimed it was before yet another “record crowd.”

The Tennessean, noting Crump was denouncing supporters of Malcolm Patterson as “gangsters and crooks”, went after “Roxie” Rice, flatly saying the generalissimo of the Shelby County machine owned “block after block of property” in Memphis which was “rented almost exclusively to prostitutes, gamblers and bootleggers.” “Do the police ever raid these joints?” the Tennessean wondered. “Of course not; they are protected by Crump and Rice and their controlled police and sheriff.” The Tennessean then proceeded to call names, citing “Dutch Mary’s joint at 214 Mulbery Street, a house of prostitution”, noting the operator of the house of ill repute also ran “a beer joint in Northeast Memphis called the Hill Top.” The Tennessean complained Dutch Mary had never been arrested as “she has been Crump – Rice guaranteed protection.” Another low brow enterprise singled out by the Tennessean was Peraccini’s, a “policy gambling house and saloon” located at 202 South Second Street. The Tennessean claimed the Shelby County machine “taxes each policy game $200 per month”, which was collected not for graft, but campaign expenditures. Despite being operated by Italians, the Tennessean said the patrons were “mostly negroes, whom Landlord Rice votes for Crump political purity at each election.” Near “a negro restaurant run by a Greek” was a pawnshop and an “alley about four feet wide.” Evidently the alley way led to the “back door of the negro dice house” where visitors could gamble and enjoy whisky. Once again, Frank Rice owned the building. The Tennessean reporter noted walking beneath a banner proclaiming, “Crump for Congress – – – McAlister for governor. Run the crooks off capitol hill!”

Increasingly both Malcolm Patterson and the Tennessean raised the issue of black participation in the coming Democratic primaries. It was a theme Lewis Pope would hammer home in the general election after refusing to accept the verdict of Tennessee Democrats. The very idea that African-Americans would be allowed to vote rankled many Democrats, especially in Middle Tennessee where the Tennessean’s influence was the greatest. The complaint was extended to the Howse machine in Nashville, as blacks were also permitted to vote in Davidson County. A headline in the Tennessean two weeks before the primary trumpeted, “Crump’s Negro Votes Would Destroy Democracy In State.”

Congressman Crump engaged in a bitter exchange with Idaho U. S. senator William E. Borah who had charged the Shelby County machine was distributing “red Cross flour in exchange for votes.” The accusation was made in spite of the fact a national employee said “there was no foundation” to Borah’s accusation. The Red Cross had also quickly insisted “Crump’s organization had nothing to do with this relief work.” Crump immediately wired Borah demanding an apology. After not hearing from Senator Borah, Crump sent another wire stating, “Your silence in not correcting a dastardly falsehood forces one to the inevitable conclusion that you are big and mighty enough to commit a low and despicable injustice and get away with it.

“If you had an ounce of real manly courage in your makeup, you would at least try to tell the truth and acknowledge your error and I say to you in a most positive way you will do it some day.”

The Memphis Boss knew he had been wounded by the charge made by Borah and acknowledged it. “You have done me an irreparable injury all over this country, and common decency on your part should have made it unnecessary to call it to your attention more than once.” Irascible and contrary, the independent-minded Borah then immediately publicly refused to apologize. Crump retorted Senator Borah had most certainly done him an injustice but “just isn’t big enough to admit” it. The Memphis Boss might well have had a legitimate complaint, as there was no real evidence to support Borah’s charges.

The campaign would only grow more bitter.