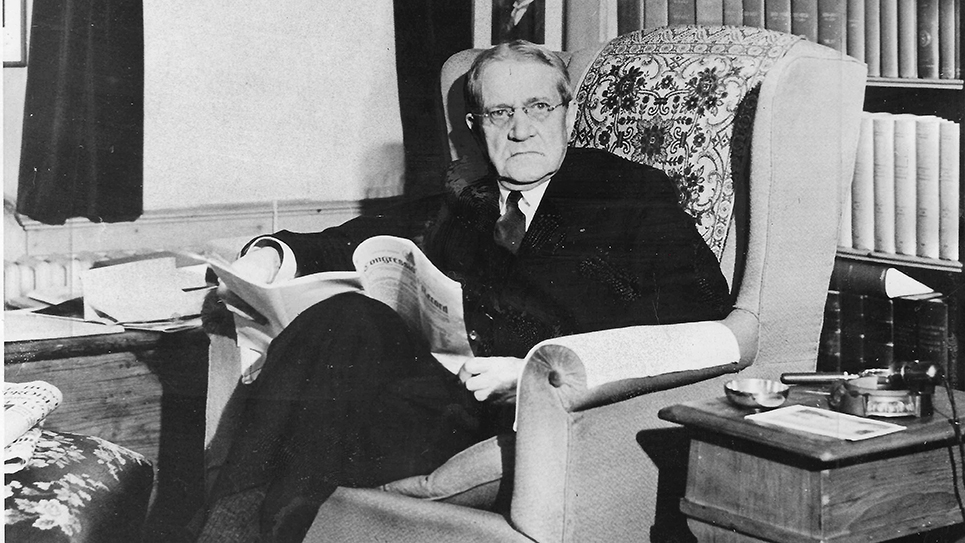

Prentice Cooper of Shelbyville, three times governor of Tennessee, had announced he would once again seek to become the Volunteer State’s chief executive on New Year’s day in 1958. The sixty-two year old Cooper was one of many prospective candidates all of whom were warily circling one another. Prentice Cooper’s own announcement seemed to come something as a surprise although he had been considering the race for several months. The former governor’s announcement was made in the form of telegrams sent to major newspapers across the state and seemed somewhat rushed. Cooper very well might have been attempting to beat Judge Andrew “Tip” Taylor to the draw, perhaps in the hope Taylor might reconsider and choose not to become a candidate. Cooper and Taylor had a history together; Taylor had managed Cooper’s successful 1938 gubernatorial campaign in West Tennessee. Cooper then appointed the twenty-eight year old Taylor as Tennessee’s Commissioner of Institutions. Andrew Taylor remained the youngest person in Tennessee’s history to serve in a governor’s cabinet.

If Prentice Cooper believed an early announcement would bluff “Tip” Taylor out of the gubernatorial race, he was mistaken. Within weeks there would be six candidates for the Democratic nomination in the field, including Edmund Orgill, the mayor of Memphis; Buford Ellington, Commissioner of Agriculture in the cabinet of outgoing governor Frank Clement; and “Tip” Taylor, who seemed to be drawing significant support from his native West Tennessee. Ellington had the advantage of being perceived as the candidate of the Clement organization, which gave him a significant boost in organizing his campaign. Initially, Cooper began his campaign, opening his state headquarters in Nashville’s Hermitage Hotel. The former governor made modest trips across the state, sometimes accompanied by his pretty and much younger wife. Despite his age, Prentice Cooper not only had a young wife, but three very young sons, the youngest of whom was only 15 months old.

After pursuing the gubernatorial nomination for a few months, rumors began to circulate Prentice Cooper was being urged to enter the race for the United States Senate seat occupied by Albert Gore. There were numerous reasons why his competitors and their supporters in the governor’s race would have been delighted to see Cooper challenge Gore. Cooper was something of a wild card in the gubernatorial race and while he might not win, the former governor seemed sure to draw a good vote. In a field with as many as six or seven candidates, it was difficult to say just how things might shake out.

Albert Gore was fifty years old and completing his first term in the U. S. Senate. Despite his relatively youthful age, Gore was a veteran of Congress, having served fourteen years in the House of Representatives before toppling Senator Kenneth McKellar in the 1952 Democratic primary. McKellar was about as entrenched as most any incumbent could be when Gore challenged him and to this day remains Tennessee’s longest serving senator. Gore entered the Senate as something of a giant-killer and while Governor Frank Clement considered for a time a race against Tennessee’s junior senator, he thought better of it. Gore had not drawn a serious opponent by May of 1958 and Prentice Cooper had long wanted to go to the Senate. Cooper had pondered foregoing a race for a third term as governor in 1942 and challenging Senator Tom Stewart. Cooper likely also hoped the venerable McKellar would retire in 1946 and thought about a senatorial campaign once again in 1948.

The rumor about Prentice Cooper switching races was so prevalent by the end of May that he felt compelled to deny them. “I’m in the race for governor of Tennessee and I’m going to fight a good fight,” Cooper said.

Cooper was not only being encouraged to run for the Senate by conservative Democrats, but by Republicans as well. Guy Smith, editor of the Knoxville Journal, and prominent in Tennessee GOP affairs, had been busy lining up support for Cooper. The Jackson Sun noted petitions qualifying Prentice Cooper to run for the U. S. Senate were being circulated locally. On June 5, 1958 Prentice Cooper made it official. He was withdrawing as a candidate for the Democratic nomination for governor and entering the primary to challenge Senator Albert Gore. Cooper did a fairly deft about face, saying he had become a candidate for the senatorial nomination because “my opponent has turned his back on Tennessee to further his own political ambitions rather than serve the people who elected him.” The former governor was not shy about expressing his dissatisfaction with Gore and said he was “opposed to unsound global give-away theories which not only contribute to unemployment in Tennessee but threaten the very existence of our nation.” Cooper complained Gore had joined with Americans for Democratic Action, the NAACP and “Northern liberals” in an effort to “force our children into unwarranted social mixing.”

“He helped remove Tennessee as part of the South by joining with Northern zealots who would take away our Southern way of living,” Cooper thundered.

Speaking to a press conference from his state headquarters in Nashville, Prentice Cooper said he would begin his campaign immediately and intended to invite Senator Gore to meet him in debate.

Senator Gore had already charged Republicans with interfering in the Democratic primary. Gore took to the floor of the United States Senate to charge Guy Smith, editor of the Knoxville Journal and Meade Alcorn, Chairman of the Republican National Committee, had induced Prentice Cooper to make the switch.. Gore had found his target for Smith hotly denied he was injecting himself or fellow Republicans in the Democratic primary. “Senator Gore’s attacks upon me as Republican state chairman is typical of his unfamiliarity with what goes on in Tennessee,” Smith huffed, “and with his preoccupation with global affairs.” Smith pointed out he had resigned as state chairman of the Tennessee GOP in February of that year and claimed to “have retired from politics.” Smith could not possibly deny the fact he had urged Prentice Cooper to run for the United States Senate, writing an editorial in the Journal practically begging the former governor to run against Gore. Smith said that his efforts on behalf of Cooper were done “strictly as a private citizen.” Smith readily admitted Cooper’s announcement “delighted me” in his capacity as a private citizen. “If we cannot have a Republican Senator in this state,” Smith primly declared, “then by all means I am for having a Democrat who is not simply using his position with the state’s electorate as a platform from which to become either a candidate for president or global statesman.”

Prentice Cooper’s announcement he was running for the United States Senate against Albert Gore brought him the immediate endorsement of Citizens for Progress, a group headed by David Harsh, who promptly issued a statement of support for the former governor. Harsh opined Tennessee needed a senator who would be more interested in Tennessee than far away nations most Tennesseans would have trouble locating on a globe. Harsh said he believed “Mr. Cooper has demonstrated sincere interest in our affairs and a thorough knowledge of our problems” and was “thoroughly qualified to perform the duties of a senator.”

With only two months until the primary election, Cooper’s senatorial campaign got off to a quick start and seemed to be very well funded. It soon became readily apparent Cooper intended to pitch his campaign to more conservative Democrats, a tactic followed by Congressman Pat Sutton who had challenged Senator Estes Kefauver in 1954 with disastrous results.

Neither Kefauver nor Gore had signed the “Southern Manifesto,” which been approved by every Southern senator save for Gore, Kefauver and Lyndon Johnson of Texas. The Southern Manifesto, or Declaration of Constitutional Principles, was a document, which stated the South’s opposition to racial integration of public areas throughout the region and was authored by several Southern congressmen and senators.

The document had been signed by 101 congressmen and senators, all Democrats save for two Republicans, Joel Broyhill and Richard Poff, both from Virginia. The only other prominent Southern Democrat who refused to sign the manifesto was House Speaker Sam Rayburn of Texas.

Gore’s refusal to sign the manifesto in 1956 was a sore spot with some Tennessee Democrats, especially in West Tennessee. Cooper’s own position was quite clear. The former governor was against the “compulsion to settle social problems” through legislation.

“I do not feel we should force race-mixing,” Cooper said, “when elected as your Senator, I will do my best to preserve the Southern way of life and prevent our freedoms from being violated…not as my opponent, who has continually voted with the NAACP.” Cooper also sounded the theme much of the foreign aid approved by Congress was “wasted.” Noting the United States had spent 70 billion dollars on “our global give-away policy,” the former governor claimed at least “52 billion has been wasted.” Cooper insisted, “Good will is generated by honest dealing, not by global giveaway.”

Senator Gore, with a head of prematurely gray hair, was an adroit and shrewd campaigner, later called Tennessee’s “Old Gray Fox.” Gore was taking nothing for granted and announced he would campaign in all ninety-five of Tennessee’s counties in the two months before the primary election. Despite his vigorous campaign schedule, Senator Gore was careful to note he would travel by plane to Washington, D. C. should his vote be needed on any vital legislation. “You might say I’ll be on the double,” the senator said.

Gore had experience in campaigning against an older opponent. When first elected to the United States Senate, Gore had been a youthful forty-four, while Senator McKellar had been almost forty years older. Prentice Cooper was twelve years older than Gore, but with an attractive, much younger wife and three very small sons, the former governor was not as vulnerable as McKellar had been in 1952. Nor was Prentice Cooper ailing as K. D. McKellar was when he faced Albert Gore in the Democratic primary.

Senator Gore had been taken by surprise when Prentice Cooper announced his withdrawal from the gubernatorial race and switching to the Senate race. Gore scrambled to be prepared to meet Cooper’s challenge. According to the Nashville Tennessean’s political columnist, Joe Hatcher, at least one source of campaign funds for Prentice Cooper came from disgruntled insurance executives who had been displeased by Gore’s fierce opposition to a “bill forgiving the companies of an estimated $124 million in income taxes owed for 1957.” Gore had pointed out the bill allowed insurance companies to pay a paltry 7.8% in taxes while other companies were taxed at a whopping 52%.

Joe Hatcher was never an unbiased reporter as he almost invariably followed the line of his newspaper. The Tennessean strongly supported both Estes Kefauver and Albert Gore and the newspaper was highly antagonistic toward Governor Frank Clement. Hatcher gave full credit for Prentice Cooper’s shift in campaigns to “the Clement – Ellington machine…”

Hatcher wrote that Cooper’s attempted gubernatorial comeback was “a thorn in the flesh of the Clement – Ellington setup,” as it would pull votes from Buford Ellington. Joe Hatcher claimed part of the lure to Cooper in making the switch was the promise of the Clement administration and the Ellington organization to provide not only organizational assistance, but also substantial financial help. While it is certainly true much of the Clement organization was not especially friendly to Albert Gore, it was equally true Prentice Cooper was a wealthy man personally and there were enough special interests who had been displeased by Senator Gore’s record to supply more than enough cash to run a statewide race.

With Prentice Cooper’s announcement he would challenge Albert Gore in the 1958 Democratic primary, the Senate campaign had most certainly become a real race.