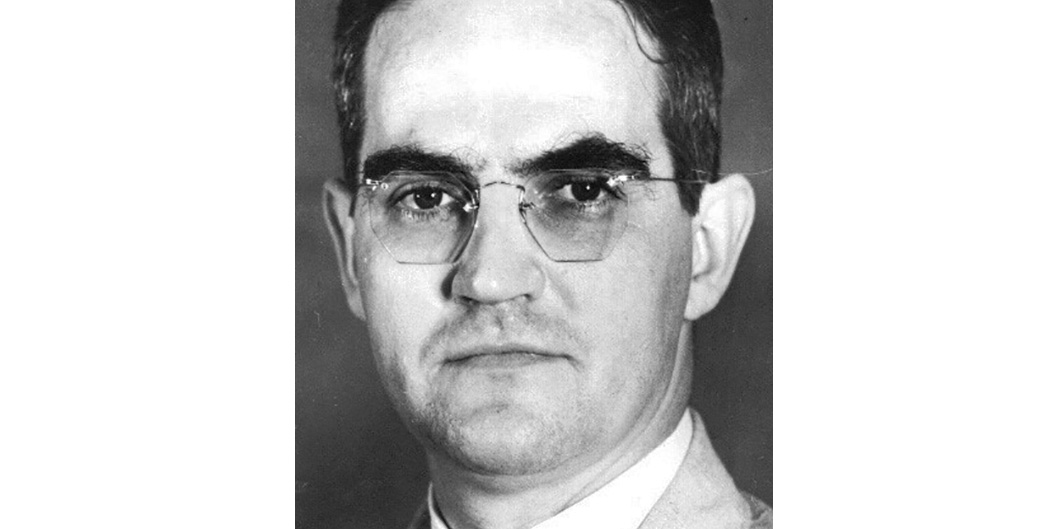

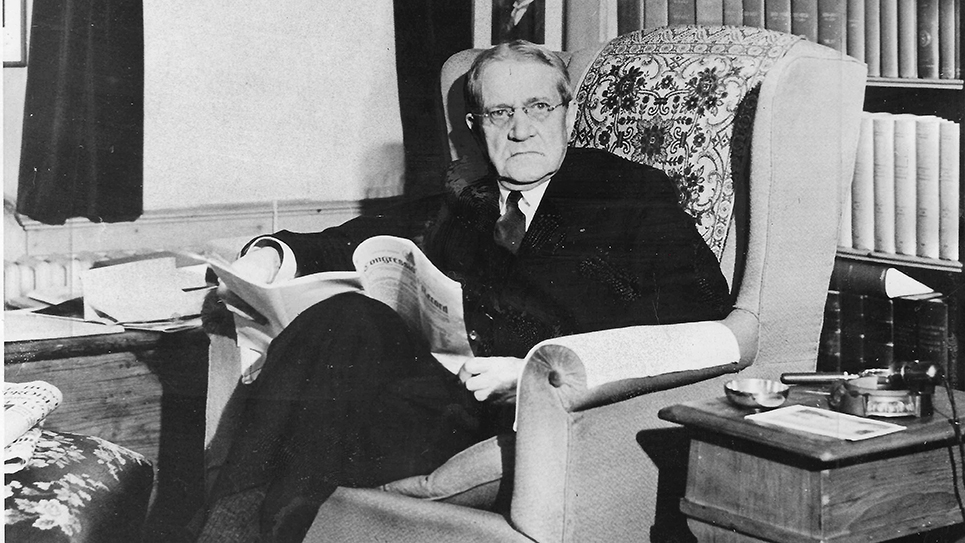

For twenty-eight years, the congressman from Tennessee’s “Hermitage District” had been Joseph W. Byrns. Congressman Byrns was a beloved figure inside the Fifth Congressional district and had been Speaker of the U. S. House of Representatives when he had died suddenly on June 4, 1936. Some urged Joseph W. Byrns, Jr., the late Speaker’s only child, to become a candidate to succeed his father. The younger Byrns, an attorney working for a federal agency in Nashville, had opted not to become a candidate. The Hermitage District, or Tennessee’s Fifth Congressional district, was as solidly Democratic as had been General Andrew Jackson. The congressman would be selected in the Democratic primary and the three leading contenders in the 1936 primary had been Richard M. Atkinson, Will T. Cheek and J. Carlton Loser. Atkinson had been the attorney general for the Tenth District for eight years and was something of a controversial figure. Atkinson won 14,144 votes to 14,131 for Will Cheek, a difference of exactly 13 votes. Loser was not that far behind with 12,591 votes.

Congressman Atkinson did little to endear himself to his constituents by parting ways with President Franklin D. Roosevelt on a few pieces of New Deal legislation. Byrns had been recommended by Tennessee’s two U. S. senators, Kenneth D. McKellar and George L. Berry, for a federal appointment which mysteriously went nowhere. Before that issue was settled, Byrns had announced he would run to unseat Congressman Richard M. Atkinson inside the 1938 Democratic primary. Perhaps anticipating an announcement by Byrns, Atkinson had proceeded to rile the peppery Senator McKellar by proposing to fire William M. Gupton, Nashville’s postmaster, when his term expired in January of 1938. Normally, a congressman was well within his or her rights to name the postmaster of his or her home city, but McKellar was undisputedly the most powerful member of Tennessee’s Congressional delegation. Moreover, McKellar was also the Chairman of the Senate Post Office & Post Roads Committee. McKellar wrote Postmaster General James A. Farley and flatly declared dismissing Gupton would be considered a personal affront by the senator.

Gupton had been originally appointed by the late Speaker Jo Byrns and Congressman Atkinson doubtless suspected the postmaster would remain loyal to the family and give what political aid he could to the younger Byrns. Yet Atkinson knew he could not hope to win a political brawl with McKellar, who was a stalwart of the New Deal administration.

Atkinson knew Joe Byrns, Jr. could draw on the extensive political network his father had established in almost thirty years in Congress. Byrns threw down the gauntlet, saying he would back the President and was critical of Atkinson having taken positions which were coincidentally those taken by Republicans in Congress. Byrns “pledged himself to support agricultural legislation, the extension of civil service in all phases of government, whole-hearted support of TVA and the CVA and other measures” the young candidate believed would benefit the Hermitage District.

Byrns did leave himself an out in pledging support for Franklin Roosevelt; the candidate said he would only refuse to back the President should FDR go against the interests of the people. As he finished his opening speech of the campaign in Clarksville, a little girl, Betty Pearl Miller, approached the dais and presented Byrns with a basket of flowers. The young candidate made a hit with the home folks when he asked that the flowers be placed on the grave of the late Governor Austin Peay, a native of Clarksville.

While stumping in Gallatin, Tennessee, Joe Byrns, Jr. promised to support rural electrification, old age pensions and “the extension of social justice under an economy program.” Byrns had been especially critical of the 65 roll call votes Atkinson had missed and pledged, “I shall be on the job all the time. I mean to have a share in fashioning the safe future of America.”

As Joe Byrns, Jr. campaigned throughout Tennessee’s Hermitage District, incumbent Richard M. Atkinson was hardly idle. Atkinson opened his campaign headquarters in Nashville’s Noel Hotel and made his announcement he would run for reelection on July 2, 1938. Perhaps sensitive to the repeated charges of disloyalty to President Roosevelt, Atkinson said, “I believe I have gained the confidence and respect of our President, as well as of the entire membership of the House of Representatives.” Atkinson quoted a letter he had received from Majority Leader Sam Rayburn stating the Texan’s “warm regard for me, and his appreciation of my service to the Democratic Party.” Congressman Atkinson defended himself from accusations he had betrayed President Roosevelt. After praising FDR, Atkinson said in a statement, “…when I am convinced that his recommendations are contrary to the fundamental doctrines of our Republic, or contrary to the best interests of this District, I reserve the right to follow the dictates of my conscience and judgment alone.” Atkinson went to some length to review the New Deal legislation he had supported during his year and a half in Congress.

Atkinson began a whirlwind tour of speaking engagements through towns small and out-of-the-way hamlets. Nor did Atkinson ignore the cities or special interests; the Congressman spoke to the Tennessee Rural Letter Carriers Association meeting in convention, as well as the veterans. As Joseph W. Byrns, Jr. opened his congressional campaign in Clarksville, Richard Atkinson opened his own drive for renomination in Hartsville, Tennessee. Congressman Atkinson did what all incumbents do – – – bragged on his recorded, but he also defended his disagreements with FDR on higher interest rates on farm loans, veterans’ aid bills and the wage and hour bill.

While campaigning in a rural community in Davidson County, Atkinson stated he had opposed the administration’s proposed reorganization of the federal government because of his belief it invested too much power in the chief executive. Congressman Atkinson reminded his audience Franklin Roosevelt would not always be President of the United States and a “reactionary” chief executive might follow FDR into office and utilized the same authority to reorganize the government. Atkinson sniffed Joseph W. Byrns, Jr. was “so unlike his father that no trace of the late Speaker’s characteristics could be found in his son.”

Byrns charged Atkinson with an attempt to use “a form letter” sent by House Speaker William B. Bankhead to every Democratic congressman at the close of the session to further his own candidacy. Joe Byrns scoffed at the idea any Democrat of prominence had endorsed Congressman Atkinson’s candidacy. Byrns released the text of a telegram sent to him by Speaker Bankhead. “The letter written by me to Mr. Atkinson was similar in content to one which I addressed to the Democratic members of Congress upon adjournment,” Bankhead admitted. “This letter was not intended to be an indorsement for nomination over other Democratic candidates, as it is my consistent policy not to express favoritism between primary Democrats in a party.” Byrns once again pummeled Atkinson for having missed 65 roll call votes and promised voters he would remain on the job.

Congressman Atkinson angrily retorted Byrns was the political pawn of a local “beer baron.” Speaking in Nashville, Richard Atkinson roared his indignation at what he termed Byrns’s “trickery.” The Congressman specifically said Byrns was being dishonest when the candidate accused him of having missed 65 roll calls votes. Yet, Atkinson explained there were numerous “roll calls” in the House and many were simply “unimportant” or of no consequence. “My opponent did not tell you I was in bed two weeks” due to recovery from an operation “and for another ten days investigating government hospitals on a Congressional committee and at other times aiding some local delegation in Washington on a mission for the folks at home.”

Byrns lobbed another charge at Congressman Atkinson while speaking in Springfield, Tennessee. Byrns accused Atkinson of having “walked out” on the farmers of Tennessee’s Hermitage District. Joe Byrns, Jr. said Congressman Atkinson was in Nashville when Congress had voted on the Agricultural Adjustment Act. Byrns snorted Atkinson had claimed he was acting as a one-man congressional committee to investigate government hospitals; Byrns pointed out the only government hospitals in Tennessee were located in Johnson City and Memphis.

“Any man who goes to Washington to represent the farmers of his district and walks out on them is not a representative, but a misrepresentative,” Byrns cried.

Congressman Atkinson, campaigning in Flat Rock, seemed exasperated and snapped Byrns was making “untrue statements.” Atkinson said the idea he “had broken with President Roosevelt” was little more than “ridiculous.” The Congressman insisted FDR was his personal friend.

Joe Byrns, Jr., namesake of his father and certainly the beneficiary of his dead father’s political legacy inside the Hermitage District, tried having it both ways when he denied he was trying to win election to Congress on his late father’s record. The younger Byrns did say, somewhat disingenuously, he was, of course, well acquainted with congressional issues and counted many friends amongst the senior members of Congress because of his family ties.

The importance of the Cumberland River in Middle Tennessee was understood by virtually everyone and both Congressman Richard Atkinson and challenger Joseph W. Byrns, Jr. tried to outdo the other in promising to work for flood control and power development along the Cumberland. Campaigning at the McFerrin Fair Grounds, Byrns poked fun at his opponent, depicting Atkinson as a victim of his own success. Byrns drew a portrait for his listeners of a freshman congressman awed by being in Congress, which the candidate termed as “gone upstage.” Byrns said Atkinson had participated in “fashion parades” with his small dog Mickey. Apparently, the congressman had fallen prey to the bug of sartorial elegance. Byrns oddly accused Atkinson of being a “commuter” between Washington, D. C. and the Hermitage District. “I will support any workable old-age pension plan,” Byrns promised. “I will always oppose a wage differential for Southern workers, and I will be in Washington when Congress is in session.” Byrns had slightly changed his story about Atkinson having missed voting on the Agricultural Adjustment Act. Now Byrns said while Congress was voting on the AAA, Atkinson was in Nashville dedicating the Supreme Court Building while “criticizing the greatest President the United States ever had.”

During the last week of the campaign, Congressman Atkinson was still downplaying his opposition to some of President Roosevelt’s policies. Atkinson also added a rather bizarre new charge that Joe Byrns, Jr. had admitted he had destroyed his father’s personal papers following the Speaker’s death. Atkinson mused over “how fond” many New Deal administration officials were of him and recalled “the President and I have laughed together over the few times I have differed with administration policy.”

Within days of the primary election, the Johnson City Chronicle published a story about the congressional campaign in the Hermitage District. The Chronicle summarized the issue originally stated by Joseph W. Byrns, Jr.: the sole issue was pro-Roosevelt or anti-Roosevelt. Congressman Atkinson furiously retorted, “Anyone who pledges to conduct himself according to the dictates of any person is not qualified to represent the people.” Atkinson insisted, “I have kept the faith with my people. I have refused to violate my conscience.” The Chronicle noted even the congressman’s “garb” had become a campaign issue, as well as his travels to New York City, Nashville, and Atlantic City while Congress was in session. Atkinson complained that the Byrns campaign was being run by former U. S. senator Luke Lea. The Congressman said bitterly Colonel Lea “sings his song of hate to my opponent and makes him repeat it.”

The election results were surprisingly close. Joseph W. Byrns, Jr. won the Democratic primary with 19,227 votes. Richard M. Atkinson won the endorsement of 18,195 voters in Tennessee’s Hermitage District. Byrns had won by a margin of 1032 votes. Joseph W. Byrns, Jr., at age thirty-four, was going to Washington.