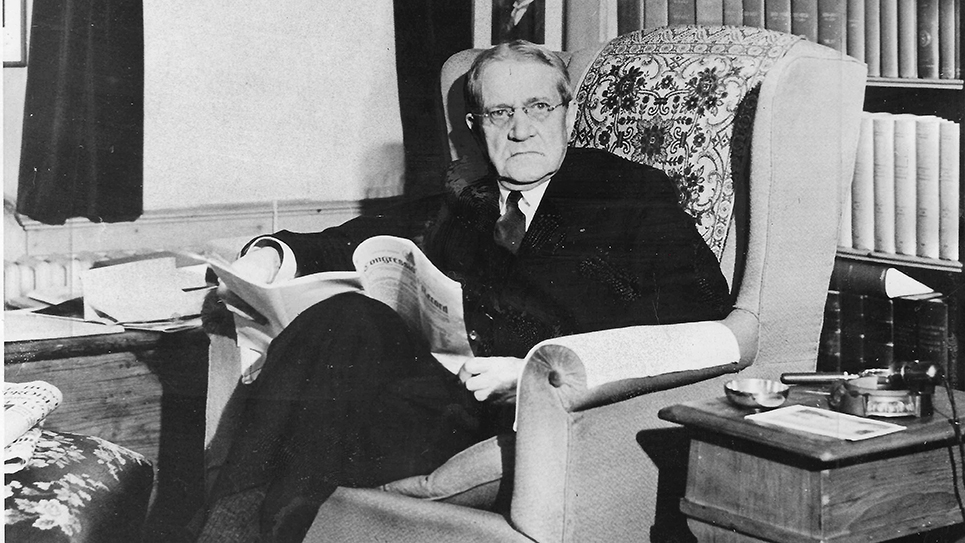

Joseph W. Byrns, Jr. had successfully managed to defeat freshman Congressman Richard Atkinson in a hard fought race. The Democratic nominee – – – and the general election in the Hermitage District was a mere formality, as it was as Democratic as had been the owner of the Hermitage, General Andrew Jackson. For twenty-eight years, the congressman from the Hermitage District had been Joseph W. Byrns. By the time he died unexpectedly in June of 1936, Jo Byrns was Speaker of the U. S. House of Representatives. His son had declined to run for Congress to succeed his father in 1936, but had run two years later. The thirty-four year old Byrns vaguely resembled his father; one could certainly see Jo Byrns in the features of the son. Like the late Speaker, Joe Byrns, Jr. was seldom seen without a cigar in hand.

Byrns had run for Congress as an ardent supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and had made much of the few times Congressman Atkinson had parted company with the President. It has been a close race and the Hermitage District was composed of seven counties: Davidson, Macon, Montgomery, Robertson, Stewart, Sumner and Trousdale. Atkinson had carried every county in the district except Davidson. Byrns had run well enough that his margin inside Davidson County proved to be decisive.

As the primary campaign had come to a close, Richard Atkinson made the astonishing charge Joe Byrns, Jr. had earned the then princely sum of $20,000 annually from holding no less than three government jobs. Byrns snarled the accusation was nothing less than “a malicious lie.” During one of his last personal appearances before the election, the younger Byrns declared, “My father instilled into me two principles before his death, first, that I was no better than anyone else, and second, that the man in a hickory shirt and blue overalls would stand by me long after the man in the silk hat tromped on me.”

As Byrns celebrated his victory, he was heartened by a letter he received from President Roosevelt, which the young congressional candidate quickly made public. FDR congratulated Byrns upon his victory in the Democratic primary and expressed special pleasure “to learn that your majority was about the same as your father received in his first campaign 30 years ago.” The letter from President Roosevelt somewhat dampened the idea FDR was the warm personal friend of Congressman Richard M. Atkinson. Ironically, the President had engaged in his infamous “purge” to rid the United States Senate of those apostates who had given him such trouble when he sought to expand the U. S. Supreme Court. That bid to defeat truculent senators had been an abysmal failure, much to Roosevelt’s chagrin and embarrassment.

Richard Atkinson was at least smart enough or loyal enough to his political party to join a drive to campaign all across Tennessee by a united Democratic party. Tennessee Democrats had witnessed a titanic struggle between two factions of the Democratic Party; one faction consisted of Senator Kenneth D. McKellar and E. H. Crump, leader of the Shelby County political organization. The other faction was headed by Governor Gordon Browning. McKellar and Crump had parted political company by supporting competing candidates for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 1936. McKellar had backed Burgin Dossett, while Crump made no endorsement until late in the primary campaign. The Memphis Boss had finally announced he was for Browning. Gordon Browning, a former twelve-year veteran of Congress, had made a credible statewide race against Senator Nathan L. Bachman in 1934, but lost. McKellar, who rightly suspected Browning had a strong yearning to sit in the United States Senate, was thoroughly opposed to any political advancement for the former congressman. Crump likely calculated Burgin Dossett’s candidacy was not resonating with Tennessee Democrats and chose to endorse Gordon Browning, who won 60,000 votes in Crump’s domain of Shelby County. The heavy majority given to Browning in Shelby County did not put the former congressman over the top in the primary; Browning would have won even had the Memphis Boss chosen to support Burgin Dossett.

The alliance between Crump and Browning did not last long. Nathan L. Bachman died in April of 1937, just four months into a new six-year term of office. Browning journeyed to Memphis where, according to Crump, the governor proposed a trade. Governor Browning wanted to run for the U. S. Senate in 1938 against his own appointee, George L. Berry and wanted Crump’s support for himself and Lewis Pope for governor; in return, Browning and Pope would support Crump for the Senate in 1940 against McKellar. The Memphis Boss made the logical observation had Browning wanted Crump in the Senate, he could have been appointed instead of George L. Berry. Whatever the circumstances surrounding the private conversation of Browning and Crump, the end result was the governor returned to Nashville and launched an all-out assault on the Shelby County machine, culminating in a fierce struggle inside the Tennessee General Assembly when Browning attempted to force through a “county unit” bill that would have made the big majorities produced by Shelby County meaningless. Crump, shocked and stung, found himself in a fight for his political life and had to run to Senator McKellar for aid and comfort. McKellar readily joined his old friend in fighting off the county unit bill. The 1938 election in Tennessee had been hard fought and a bitter contest between the two factions and was won by McKellar and Crump.

The bitterness of the infighting necessitated a unified effort by Tennessee Democrats against the Republicans in the fall. Several candidates who had lost in bitterly contested Democratic primaries joined the victors on the campaign trail in the fall, including Dick Atkinson. The willingness of Atkinson to stump for his fellow Democrats was likely an indication he was not through with politics and had his eye on running for office in the future.

Joseph W. Byrns, Jr. was welcomed to Washington by Senator McKellar, who had long been friends with the new congressman’s parents. The newly elected congressman told reporters he hoped for an assignment to the House Agriculture Committee, which likely gives readers an idea of how rural the Hermitage District was in 1939 compared to today. The Nashville Tennessean published a photograph of Byrns shaking hands with House Speaker William B. Bankhead beneath a portrait of the late Joseph W. Byrns. The younger Byrns had taken the oath of office as it was administered by Speaker Bankhead and witnessed by his wife and mother. Byrns stood beside another newly elected congressman from a district adjoining his own, Albert Gore. Both Byrns and Gore cast their first votes as Members of Congress by voting for William Bankhead to serve as Speaker of the House.

The widow of Speaker Byrns had seen the official portrait of her husband previously, but wandered down the Speaker’s corridor where it now hung. Mrs. Byrns, wife of one congressman and the mother of another, gazed at the likeness of her husband before leaving to rejoin her son and daughter-in-law.

On January 12, Joe Byrns, Jr. presided over the House of Representatives, something his father had done many times, as the House considered the deficiency relief appropriation. Speaker Bankhead left the presiding officer’s chair and gave the gavel to the congressman from Tennessee’s Hermitage District. Byrns remained in the Speaker’s chair for two hours while members debated the merits of the bill. Mrs. Joseph W. Byrns watched her son preside over the House from the gallery.

Congressman Joe Byrns, Jr. and his wife attended their first White House reception on the evening of January 19, 1939. It was President Roosevelt’s reception in honor of the Members of Congress. Mrs. Byrns made an impression in “a crepe gown of deepest pink and pale rose, with two gardenias in her hair.” Byrns was appointed to serve on the House Committee on Post Offices & Post Roads, while his colleague Albert Gore was assigned to the Banking and Currency Committee. More surprising still, Byrns was the only freshman member of Congress to be appointed to the chairmanship of a subcommittee. At thirty-four, Joseph W. Byrns, Jr. had the prospect of a long and successful career in the House of Representatives.

Byrns quickly made headlines when he sent a letter to Congressman John J. Cochran, Chairman of the Committee on Expenditures in the Executive Department, taking aim at his former employer, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. The Byrns missive was interesting because he had been an attorney for the HOLC before being elected to Congress, as well as his assertion it was “the most mismanaged independent agency” of government. Congressman Byrns charged Charles A. Jones, general manager of the HOLC, with having violated the law by utilizing taxpayer funds to lobby against legislation. In his letter to Cochran, Byrns wrote, “Between the middle and latter part of October, 1937, Mr. Jones interested himself in a bill pending before Congress, introduced by Ellenbogen of Pennsylvania to reduce the rate of interest on Home Owners’ Loan Corporation loans and to extend the time for their maturity.” Byrns went on to detail the supposed misuse of public funds by Charles Jones as having used “the long distance, at government expense, and the government frank (the free mailing privilege enjoyed by Members of Congress and various government agencies) in sending throughout the country copies of a statement made by him lobbying against the Ellenbogen bill in a direct attempt to get people throughout the country to write their representatives to vote against the bill.”

Congressman Byrns wrote he believed it was “a violation of the United States criminal code prohibiting use of appropriations to pay for personal service to influence members of Congress to favor or oppose legislation.” Byrns having been employed by HOLC gave weight to his accusations.

Byrns did not long remain on the House Committee on Post Offices & Post Roads. In what appeared to be another sign Joe Byrns, Jr. was a favorite of the House leadership, the young congressman was elevated to membership on the House Military Affairs Committee, taking the place of the late Clarence W. Turner of Tennessee. The appointment of Byrns was unanimously approved by the Democratic members of the Ways & Means Committee, which doled out committee assignments for the members of their party. The appointment of Byrns to the Military Affairs Committee was duly noted in Tennessee, especially as it dealt with projects of importance to the Volunteer State, not the least of which was the Tennessee Valley Authority. The Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle noted the appointment of Byrns to the committee in an approving editorial. Governor Prentice Cooper selected Joe Byrns, Jr. as Tennessee’s designated representative for the observance of “Tennessee Day” at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania in April of 1939. The young congressman was also the principle speaker at the National Exchange Club state convention held in Richmond, Virginia.

The most anticipated social event in Washington, D. C. in 1939 was the visit of King George and his Queen, Mary. When it was announced a party would be held for a group of carefully chosen senators and congressman at the British Embassy, Washingtonians went wild. People inundated their representatives with requests for tickets to the event. Byrns managed an invite to the reception for their Britannic Majesties, but later told reporters he was less than impressed. Byrns then made a comment many Tennesseans thought ungracious, if not down -right rude. Referring to the king and queen of Great Britain, Congress Byrns said, “What a couple of flat tires they turned out to be.” Byrns was the only member of the Tennessee Congressional delegation to say anything remotely unkind about the royal pair. Senator McKellar described the king and queen as “altogether lovely and fine.” The senator said he was “impressed by their graciousness and friendliness and sociability.”

Things would soon get much less friendly for Congressman Joe Byrns, Jr.