Colonel Luke Lea, away in Europe during the First World War, had never gotten along with John Knight Shields when they were colleagues in the United States Senate. Lea’s newspaper, the Nashville Tennessean sided with Shields’ opponent, Governor Tom Rye in the Democratic primary. According to Lea’s newspaper, Shields had made several “unholy” alliances to get himself reelected. The Tennessean stated Senator Shields had allied himself with the political machine headed by Hillary Howse in Nashville, as well as that led by E. H. Crump in Memphis and even Republicans. Worst of all, at least in Luke Lea’s eyes, was Shields’s alliance with rival publisher E. B. Stahlman, “the open and notorious Hun insulter of President Wilson and the American people.”

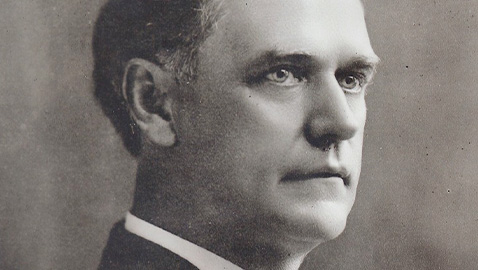

American boys were fighting a bloody war in Europe as a fierce political contest was fought between U. S. Senator John Knight Shields and Governor Tom C. Rye. The governor was attempting to wrest the Democratic nomination from Senator Shields inside the primary. It was only the second time in Tennessee’s history voters would actually select their own nominees in a binding primary contest.

Rye was an able speaker, popular with the people and had been a good governor. Dignified while remaining genial, Tom C. Rye was a sharp contrast to the peppery John Knight Shields. Many observers of the race between Shields and Rye thought the governor was gaining throughout the month of July. The race between Senator Shields and Governor Rye had much to do with support for President Woodrow Wilson. Rye promised all out support for the President, while Shields had been less than enthusiastic about Wilson and his administration.

Despite his contrary nature, John Knight Shields was not without resources, chief of which was his junior colleague, Kenneth McKellar. Loyal to a fault, McKellar had not forgotten the support he had received from Senator Shields when he ran in the 1915 primary against Senator Luke Lea and former governor Malcolm Patterson. McKellar had run exceedingly well in East Tennessee, which was the home of John Knight Shields. McKellar moved his own appointees and friends behind the senior senator and convinced E. H. Crump to back Shields. Relations between Senator Shields and Crump were virtually nonexistent. McKellar wrote that Shields had “never forgiven” Crump for the Shelby County legislative delegation having fiercely opposed him when he was elected to the U. S. Senate in 1912. McKellar admitted Crump had thrown his support to Shields “on my account.” Even more important, Senator McKellar convinced President Woodrow Wilson not to write a public letter denouncing John Knight Shields as no friend to his administration. That alone would have been enough to turn the tide against Senator Shields, as Wilson was highly popular in Tennessee, especially with fellow Democrats. Shields had assessed his own chances and thought he would run well in East and Middle Tennessee, but was worried about West Tennessee, which was the home ground of Governor Tom C. Rye. It was also the home of K. D. McKellar. Senator Shields wanted McKellar to go home to Tennessee and help his cause in the western portion of the state. McKellar was packing for his trip when he received a telephone call from John Knight Shields. Senator Shields told McKellar he had heard President Wilson intended to write a letter to a friend in Tennessee for publication. The letter would state John Knight Shields was no friend to Wilson or his administration. The President had written similar letters, which had helped to defeat at least two other Democratic senators. Shields wanted McKellar to keep the President from writing that letter. A startled McKellar promised to do all he could to prevent President Wilson from denouncing Shields. Immediately after hanging up with Shields, McKellar went to the office of Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson. McKellar related what he had been told by Senator Shields and wondered if it was true. Burleson said it was. Burleson said the President had raised the issue of writing a letter condemning Shields with the members of his Cabinet and every member save for himself had agreed Wilson should write the letter. McKellar hurried over to the White House and saw the President’s secretary, Joseph Tumulty. The presidential secretary once again confirmed Wilson intended to write such a letter, but pointed out it had yet to be written. Tumulty told McKellar he would make an appointment for the senator to see the President the following morning at 10 a.m.

Senator McKellar recalled he had never seen the President “in a more engaging frame of mind” when he entered the White House that morning. Once McKellar told Wilson why he was at the White House, the President’s attitude changed. Wilson told the senator, “McKellar, this war is going to be over in six or eight months and I am tremendously interested in the permanent peace of the world. Mr. Shields will not be for me. He has never liked me, and I have never liked him. I want a Senator who will uphold my plan of securing a permanent world peace.”

McKellar quickly replied, “Why, Mr. President I have his word that he is behind you and your aims and purposes in this war.”

Wilson was insistent. “I know; but Mr. Shields will not be for me.”

Originally scheduled for a five-minute appointment, McKellar stayed for an hour and forty minutes. The Tennessean confessed he tried every way in the world to change the President’s mind and finally resorted to quoting from a book Wilson had written on civil government, which deplored the idea of a chief executive of inappropriately attempting to influence the actions of the Congress. After reading Wilson’s own words back to him, McKellar concluded by saying it was the best argument that could be made for the President not involving himself in a contest in Tennessee. The President had the good grace to laugh and told McKellar that he had written those words while a very young man and now had a different view brought about by experience. Wilson made no commitments, but he never wrote the letter, even after former governor Malcolm Patterson, who was campaigning hard for Tom C. Rye, had wired the White House and demanded the President write the letter.

While Luke Lea’s Nashville Tennessean daily plugged the candidacy of Governor Tom C. Rye, Senator Shields had the support of many newspapers in his own East Tennessee. The Tennessean claimed the Knoxville Sentinel had refused a political advertisement for Governor Rye. The ad in question was a reprint of a speech made by Rye hitting Senator Shields hard for “aiding slackers” in the war effort. Despite paying for the ad, the Sentinel’s management refused to publish it, much to the chagrin of the Rye campaign and the Tennessean. Rye continued his theme of Shields interfering with the war effort, noting he had received a letter from a West Tennessee boy asking to serve in some other way rather than the actual battlefield. Rye, whose only son was on the staff of a general in Europe, refused to help, but claimed the young man had received assistance from Senator John Knight Shields. Speaking in Shelbyville, Tennessee, Governor Rye claimed there was only one issue in the campaign: “Win the war.” Rye pledged to follow the lead of Woodrow Wilson, to help the President in all things, and “never be absent” when his vote was needed by the Wilson administration.

Rye swept through his native West Tennessee and drew impressive crowds at a time when there was no radio or television to influence voters. Candidates flourished or sank largely due to their own abilities. The only outlet for candidates, aside from the mail, was newspaper coverage and advertising. Thousands of Tennesseans came out to hear the candidates speak and Tom C. Rye was an able orator, while John Knight Shields was a poor speaker. As the campaign drew to a close, Governor Rye invaded Memphis, the domain of E. H. Crump. Crump had yet to consolidate his hold on Shelby County and Rye was introduced to the audience by former governor Malcolm Rice Patterson. Patterson was from Memphis, had represented Shelby County in Congress, and the flamboyant former governor still had a statewide following.

Governor Tom C. Rye closed his campaign for the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate in Brownsville, Tennessee. Rye’s final appeal consisted of the governor pledging to stand by President Wilson and the Democratic Party. “You must judge a public servant his official acts,” Rye reminded his audience, “and judge a Democrat by his fealty to party and its principles.” The governor attempted to link Senator Shields with German-born E. B. Stahlman, publisher of the Nashville Banner. Clearly, at least in the mind of Tom C. Rye, Shields had allied himself with the Republicans and pro-Germans.

Oddly, Governor Rye did not attempt to exploit one potential weakness on the part of Senator Shields. Shields had been opposed to giving women the right to vote, which was a contrast with Senator McKellar. McKellar had been a strong supporter of suffrage for women and had voted for it as a congressman. It would be 1920 before every woman could vote in Tennessee, if she were able to pay the poll tax.

Election Day showed Senator John Knight Shields carrying East and Middle Tennessee, while Governor Tom C. Rye ran well in West Tennessee. Shields carried all four of Tennessee’s big urban counties. Senator Shields carried Davidson County handily over Rye, winning 4,634 votes to only 1,895 for the governor. Shields carried Knox County easily, winning 2,724 votes to a mere 787 votes for Rye. The governor fared better in Hamilton County (Chattanooga), but still lost to Senator Shields, who tallied 2,079 ballots to 1,876 for Rye. Crump’s Shelby County gave Senator Shields 6,309 votes to 4,273 for Tom C. Rye. The governor did not win significant enough margins in his own West Tennessee to mitigate losses in Middle and West Tennessee, likely because Shields had the support of his junior colleague in the United States Senate, Kenneth D. McKellar. McKellar was highly popular in West Tennessee and many of his friends and supporters backed Senator Shields.

Governor Rye was gracious in defeat and promptly sent a telegram to Senator Shields conceding defeat and offering his congratulations. Senator Shields replied by wire with his own terse acknowledgement of the governor’s telegram. “I thank you for your congratulations upon my nomination by the Democratic primary for United States Senator.”

In the end, it was K. D. McKellar who saved John Knight Shields’ seat in the United States Senate when he went to the White House to plead with President Wilson not to write the letter denouncing Shields as being hostile to his administration. McKellar, pleased by the victory of his colleague in the Democratic primary, proposed Shields join him in visiting the White House.

McKellar told his senior colleague he would accompany him to the White House so that Shields could thank both Wilson and Tumulty. To McKellar’s utter astonishment, Shields barked he would “see them in Hell first.” McKellar sadly recalled, “From that time on he fought the President and the President’s League of Nations, just as the President had predicted…” McKellar confessed, “I was tremendously embarrassed.”

The senatorial campaign in Tennessee was hardly the only disappointment Woodrow Wilson received during the 1918 Congressional campaigns. As the general election approached in the fall, President Wilson called for the voters to give him a Democratic Congress. Wilson made the mistake of making the off year election into a referendum on his own leadership and the voters responded by electing a Republican Congress. Former president Theodore Roosevelt, who had come to loathe Woodrow Wilson, chortled with delight that voters had clearly repudiated the Wilson administration. It was an ominous sign as President Wilson hurried to Paris to help negotiate the peace between the victorious allies and the defeated Central Powers after World War I.

It would also doom the President’s vision for American participation in the League of Nations.