By Ray Hill

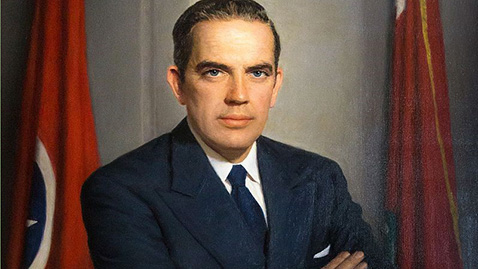

It will surprise exactly no one who knows me well to discover I have been profoundly interested in the portraits of Tennessee’s governors in our State Capitol since I knew they existed. There are many fine portraits of our various chief executives of the Volunteer State, but I have always had a few particular favorites; I have liked the portrait of redheaded Malcolm Patterson, the stately bearing of James Beriah Frazier as well as several of Tennessee’s governors from the time of my grandparents: Gordon Browning and Prentice Cooper. Some of the later governors made a profound impression upon me as well: my friend Winfield Dunn, Lamar Alexander, and Ned McWherter. The first governor that I can personally recall was Frank G. Clement and to this day my favorite portrait remains that of Governor Clement. Frank Clement, wearing a dark blue double-breasted suit and tie, his arms folded across his chest, the French cuff of his shirt peeking out of his sleeve, a serious look etched upon his face. The artist captured the intense sky blue of the young governor’s eyes, his body neatly framed by the red of the flag’s, including that of the State of Tennessee.

That same portrait was part of the dust jacket of Dr. Lee S. Greene’s unmatched biography of Frank G. Clement. I knew Dr. Greene who would occasionally regale me with bits and pieces of his knowledge of the political figures of Tennessee’s past. I still recall his telling me about his unexpected encounter with Senator K. D. McKellar on a train. For those of you who have not had the pleasure of reading Dr. Greene’s biography of Frank Clement, Lead Me On, I would highly recommend it.

We are fast approaching the 100th anniversary of the birth of Frank Goad Clement, which will be celebrated at the Frank Clement Museum in Dickson, Tennessee. The museum is located inside the old Hotel Halbrook, which is Frank Clement’s birthplace and was operated by the future governor’s family. The museum is located at 100 Frank G. Clement Place in Dickson, Tennessee. Incidentally, for those of you who love history, the Hotel Halbrook is a near-perfect example of those hostels which, once upon a time, dotted the American landscape. There were hotels near railroad depots for weary travelers to disembark and spend the night. One can see the rooms where the Clement family lived while managing the hotel and there is a trove of interesting items related to the history of Dickson County, as well as items from a time when railroad travel was prevalent in the United States. The people of Dickson and Dickson County are justly proud of the Frank G. Clement Museum. It is said Frank Clement launched his campaign to become governor of Tennessee at age ten when he told his classmates one day he would run the State of Tennessee. Frank Clement was an early achiever; he passed the Bar exam before he was old enough to practice law.

Once elected governor, Clement began an ambitious road-building program, which was especially popular with rural Tennesseans. It was Frank Clement who created the Department of Mental Health in Tennessee. Frank Clement was also the first governor in the South to veto a segregation bill passed by the legislature. Governor Clement sent Tennessee state troopers and members of the National Guard to preserve the peace and protect citizens and their property when Clinton High School was being integrated. At the time, it was an undisputed act of uncommon courage. Bob Clement has recalled the vile threats against his father’s life, as well as the governor’s family. For a while, Governor Clement found it necessary not to venture into certain parts of West Tennessee. Bobby Cain, one of the twelve black students to integrate Clinton High School, later recalled, “One of the most beautiful sights I saw in South Clinton was seeing the troopers coming in.” The governor’s sister and Chief of Staff during his last term in office, Annabelle Clement O’Brien, said, “He took an oath of office to uphold the law of the land. It was the right thing to do.”

Frank Clement married Lucille “’Cille” Christianson when they were both 19 years old.

I will never forget the first time I saw a really good photograph of Mrs. Clement. Evidently, she had daydreams about becoming a movie-star and Lucille Clement was a strikingly beautiful woman and was a gracious hostess and loving mother to her three boys.

It is likely difficult for voters today to understand just what an attractive and appealing candidate Frank G. Clement was to Tennesseans in 1952. My grandparents were probably representative of many Tennesseans of their time. My Methodist grandfather was a staunch Republican and did not like Frank Clement at all; my Baptist grandmother was from Madisonville, Tennessee, the home of Estes Kefauver, and like Estes, she was a Democrat. My grandmother never once missed voting for Frank Clement or Estes Kefauver. Still, I can remember my grandfather taking me as a little boy to meet the governor. To this day, I can recall the firm grip of my small hand in that of Frank Clement, but what I remember most was his big, warm smile and the twinkle of those blue eyes. It made quite an impression upon me. My grandmother was tickled to death to see Governor Clement again and could not help mentioning my grandfather was a Republican, adding charitably, “Well, I guess nobody’s perfect.”

Clement was running that year for the United States Senate and I still have the campaign button, which I pinned to my shirt. Once we were in the car, my grandfather removed it and replaced it with a button for Howard Baker.

Frank Clement’s personality reflected his innate love of people. One need not think every politician or vote-seeker actually really likes people; some don’t, which made television a God-send for such candidates. Frank Clement liked people and he liked crowds, where he excelled. Clement could mesmerize thousands of people who came to hear him speak. Frank Clement’s campaign spread like a wildfire throughout Tennessee. The young orator managed to put the veteran campaigner Gordon Browning on the defensive in his 1952 campaign and kept him there. Browning carried most of East Tennessee, while Frank Clement carried everything else, including Browning’s own Congressional district.

Frank Clement was the first of Tennessee’s governor’s eligible to serve a four-year term after the voters had approved a newly renovated Constitution in 1954. Running once again against his predecessor Gordon Browning, Clement carried every county in Tennessee save for Browning’s own Carroll County.

Tennessee had plenty of political talent by 1956. Estes Kefauver had run for president in 1952, but had lost the nomination to Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson who had the support of President Harry Truman. Frank Clement’s supporters had been delighted when the famous orator had been chosen to deliver the keynote speech of the 1956 Democratic National Convention. Governor Clement had few peers in speechmaking on the courthouse steps, but television proved not to be his medium. The time when candidates pressed the flesh in person and orated from hastily erected platforms, the courthouse steps or a stump was beginning to fade. The thirty-second commercial was becoming increasingly more important. While Frank Clement could draw several thousand people to hear him speak on a hot and humid night in Tennessee’s smoldering July weather, a TV commercial could reach tens of thousands of people in a matter of seconds. Clement’s keynote speech was not the success he had hoped it would be. On the convention floor, Tennesseans were divided when nominee Adlai Stevenson threw open the race for the vice-presidential nomination. Clement, Estes Kefauver and Albert Gore were all considered vice presidential prospects. A young senator from Massachusetts, John F. Kennedy, made a strong bid for the vice-presidential nomination, which was finally won by Kefauver. In yet another sign Tennessee was continuing to change, Kefauver’s popularity in Tennessee did not match that of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Once again, the GOP ticket of Eisenhower and Nixon carried the Volunteer State.

Clement almost surely could have been reelected yet again in 1958 had the Constitution not prevented it. Instead, Buford Ellington, Clement’s Commissioner of Agriculture narrowly won the Democratic nomination and general election. So began the famous “leap-frog” era of government in Tennessee. Frank Clement had given some thought to running for the U. S. Senate in 1958 when Albert Gore was seeking reelection but decided against it.

Frank Clement made his triumphant return to politics when he was reelected governor in 1962 after a four-year absence from the governor’s mansion. The death of Estes Kefauver in 1963 necessitated a special election to fill his seat in the U. S. Senate. Realizing he would eventually be out of office with few political options otherwise, Frank Clement ran for the Senate but lost the Democratic nomination to Congressman Ross Bass of Pulaski. It was Frank Clement’s first political defeat and the first time the voters of his own party had rejected his candidacy. Bass had not campaigned on national issues but rather had pounded Clement hard for having raised state taxes. Tennesseans have routinely punished governors who have raised taxes when they have sought reelection or other offices. Clement ran for the United States Senate once again in 1966 and turned around the results from the 1964 election. Governor Frank Clement beat Senator Bass in the Democratic primary. It was Frank Clement’s last great hurrah. Clement went on to lose the general election to Howard Baker, who became the first Republican to be elected to the United States Senate from Tennessee. Frank Clement certainly had not forgotten politics; when he died he was pondering a fourth campaign to reclaim the governor’s office and there is good reason to believe he would have been the Democratic nominee.

Time dims the memory but Frank Clement’s unexpected death in an automobile crash left many Tennesseans stunned and saddened. The editor of the Johnson City Press Chronicle, in a frontpage editorial, confessed he was “shocked to the point” of “numbness” by the former governor’s death. The editor wrote, “There are times and assignments in a newspaperman’s life when the job seems bigger than he can handle.” The writer admitted writing the editorial on Frank G. Clement’s passing was one of those times. The editor of the Johnson City Press thought Frank Clement “one of Tennessee’s finest governors”, but readily admitted no chief executive could achieve greatness without becoming “a controversial person.” The editor acknowledged Frank Clement was not a perfect person but thought “the greatness of his good points far overshadowed the bad ones.”

Less than seventeen years after taking the oath of office as Tennessee’s youngest governor, Frank Clement had passed way. Frank Clement had blazed brilliantly across the Tennessee sky like a meteor. Friend and foe praised the former governor as he was laid to rest in the rolling hills of his native Middle Tennessee. Perhaps former U. S. senator Ross Bass summed it up best. Bass said Frank Clement was “a fearless competitor and no man in Tennessee knew that better than I.” Nor was Frank Clement afraid to do what was right.

Frank Clement left a rich political legacy. Clement’s sister, Annabelle Clement O’Brien, was a legendary state legislator and his sons, Bob and Frank Jr., have attained high office. Bob served for years as the congressman from Davidson County, while Frank, Jr. is a highly respected judge of Tennessee’s Court of Appeals.

Now as we begin to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of his birth, Governor Clement’s legacy of accomplishments remains very much with us today. The storms of life, nor the winds and the rains, can erase the good one has done for his fellow man. As long as one remains in our memories, he or she never really dies.