By Ray Hill

Most figures in history are ephemeral and float through the pages of books only fleetingly. Some never even make the footnotes of history, yet probably should. There are any number of historical figures which were larger than life, the subject of admiration, if not adulation by students of history. George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill are but a few that come to mind. Yet, oftentimes, I come across stories that I find compelling of those people who are most certainly a part of history but remain relatively unknown.

One such figure is Marion Carpenter, a pioneering female photographer who made a name for herself in what was then most certainly a man’s world. It was Marion Carpenter who took the famous photograph of then-Vice President Harry Truman playing the piano while sultry movie star Lauren Bacall leaned back leisurely atop said piano.

Carpenter garnered front-page headlines in an altercation that highlighted the famed bean soup served in the House and Senate restaurants in the spring of 1949. Indeed, the altercation occurred inside the Senate Restaurant when Miss Marion Carpenter threw a bowl of bean soup at the head of syndicated newspaper columnist Tris Coffin. Other newspapermen clearly enjoyed reporting the incident, noting the Miss Carpenter had “wasted no motion” when she deliberately sat down beside Coffin in the Senate Restaurant and ordered bean soup, which cost all of 20 cents. Once the waiter had placed the steaming soup in front of her, Miss Carpenter promptly picked it up and threw the contents into Tris Coffin’s face. Fellow reporters gleefully reported how the beans dribbled down the stunned Coffin’s face and onto his brown corduroy jacket. After having dispatched Tris Coffin, Marion Carpenter left the restaurant.

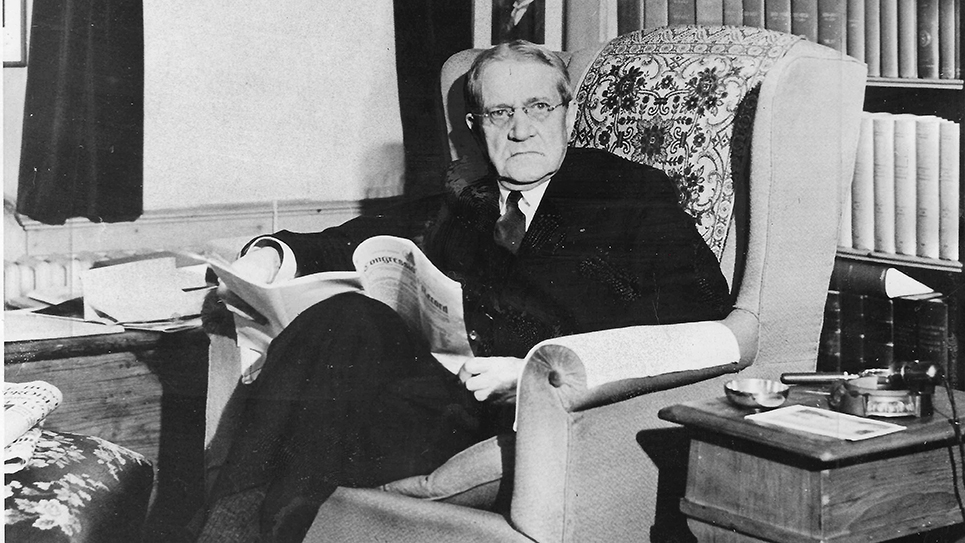

What had prompted Miss Carpenter’s fit of pique? The photographer was only too happy to explain her irritation with the newspaper columnist. Marion Carpenter explained Tris Coffin had written in a recent column the attractive photographer had “smiled and teased” congressmen into “fancy poses”, which generated income for her. It seems only natural that Tennessee’s crusty senior United States senator, Kenneth D. McKellar, himself without peer as a feudist, occupied a prominent perch in the tale. The portrait accompanying this column is a favorite of mine, taken of Senator McKellar in his office. The old senator’s personal garbage can was wrapped in the mastheads of those Tennessee newspapers who had roused the McKellar ire, including the Tennessean and the Knoxville News-Sentinel. The photograph was taken by Marion Carpenter and McKellar was the subject of Tris Coffin’s picking at one of the very few working woman photographers amongst the Washington press corps. When asked by a reporter, Miss Carpenter snapped, “Senator McKellar is a very good friend of mine. That’s all.” Marion Carpenter was an expert photographer and doubtless, there were a great many male picture-takers jealous of her talent and ability. Some snickered she required her subjects to wear makeup, a rumor which Tris Coffin repeated, which was highly unlikely and Miss Carpenter became known for some “eye-opening character studies of the greats in Congress.”

Tris Coffin groused, “Kenneth McKellar, the rheumy-eyed old man from Tennessee with a Phi Beta Kappa key swinging across his black vest, looks like a benevolent college president in Marion Carpenter’s latest.” Then came the passage which had caused him to be doused in bean soup by the outraged Marion Carpenter: “She teased and smiled him into it. The Tennessee Senator was so pleased he ordered large size, 11 to 12 inch pictures, to send to friends.”

And so he did. McKellar autographed one such photo to his friend Robert Kaspar Kistler, who served as the senator’s campaign manager in Lewis County from 1916 until his final race in 1952. McKellar never failed to carry Lewis County. Another he autographed to Secretary of the Senate, Joe Duke, which I have on the wall of my office.

Although eighty years old in 1949, Senator McKellar, a bachelor his entire life, had something of a reputation for enjoying pretty ladies and Tris Coffin clearly believed the Tennessean was susceptible to the feminine charms of Miss Carpenter. The peppery McKellar had only recently verbally set fire to a hapless utility lobbyist who was opposing a $2.5 million steam plant for the Tennessee Valley Authority. Purcell L. Smith had placed as an advertisement in the Washington Post a letter written by a CIO local in Ohio critical of the project. An angry McKellar had the ad placed in the Congressional Record and berated the unfortunate Smith before the Senate Appropriations Committee. The Tennessean lambasted Smith for placing the ad, accused him of trying to gin up opposition to the TVA steam plant and said it would be “a remarkable thing” were he to be retained at his large salary.

According to Tris Coffin, “Miss Carpenter studies the subject’s face before she gets out her makeup kit and plasters on the goo. She also arranges the background to link the Congressman and his work.” Tom Connally, the old Texan who presided as Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, had been posed with his hand on a globe “as if he had discovered it,” Coffin sneered.

Miss Carpenter certainly displayed no regrets in socking Tris Coffin in the face with a bowl of bean soup; quite to the contrary, she gladly posed for other photographers, bowl in hand, to demonstrate how she had drenched the columnist. The twenty-nine-year-old photographer was described as “an athletic brunette” who had made a living by taking freelance jobs photographing the members of Congress. Marion Carpenter had also worked at the White House and knew President Harry Truman well. Miss Carpenter was one of the first women to be a member of the White House News Photographers’ Association. Marion Carpenter was also the only woman among the photographers who followed the president when he traveled.

“I don’t have to smile or tease anyone to get them to pose,” Miss Carpenter barked to admiring reporters. The only contrition Marion Carpenter would acknowledge was her willingness to pay a $15 cleaning bill for having had the pleasure of giving Tris Coffin her opinion of his offensive column.

Senators, many of whom are not noted for their sense of humor, dourly considered barring Marion Carpenter from the Senate Restaurant in a bid to avoid any future flinging of bean soup. The matter was to be heard by the Senate Rules Committee.

The incident had been headlined by some puckish writers as “Carpenter Nails Coffin.”

The former photographer later drifted from public view. After having traveled with Harry Truman and covering him daily, Marion Carpenter got married and settled into a life far away from Washington, D. C. Miss Carpenter had first studied photography in St. Paul, Minnesota and went to Washington when she was about twenty-four. When she was plucked up to work for the Truman White House, she had been employed by the International News Photos syndicate. When she died in 2002, among her effects was a photograph she had taken of Harry Truman resolutely striding uphill toward the Washington Monument. Scribbled on the photo was a message from President Truman, “It’s good exercise if you keep it up, but not for high-heeled shoes, Miss Carpenter.”

When she died, Marion Carpenter left behind more questions than answers. “This is a story and a half,” said Beverly Allstop, a friend. “But we’ve all just got pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Marion was a very private person, and she kept a lot of things from everybody.”

One of those puzzles was her telling friends in her later life she had lost her job at the White House because of a love affair with a married man. Previously, a marriage to a Navy man who reportedly abused her ended in divorce after she recovered from one such incident after a stay in the hospital. Marion Carpenter then married a journalist, John Anderson, and they moved to Denver, Colorado where the couple had a son. Anderson was a radio announcer, but by 1951 her marriage, as well as her career, was over. To support herself and her son, Marion Carpenter moved to St. Paul, Minnesota where she worked as a nurse and had a side business as a wedding photographer.

The last part of Marion Carpenter’s life was more bitter than sweet. Some friends said her son left home and apparently Miss Carpenter never saw Mjohn again for the rest of her life. Friends were able to piece together a story where Mjohn had gotten into some difficulties with juvenile authorities and left home at age nineteen. Mjohn Anderson had moved out West and by the time she died, friends knew it had been quite a long time since Marion Carpenter had seen her only child.

Details and tidbits about her life would occasionally dribble out over the years to Marion Carpenter’s friends. Miss Carpenter had worked as a nurse from 1942 until 1944 and she had joined the St. Paul Camera Club where she became avidly interested in photography and learned the basics of her sometime profession. It was 1944 when Marion Carpenter moved to Washington, D. C. where she began working for famed publisher “Cissy” Patterson’s Washington Times-Herald newspaper as a photographer. To supplement her income, she began doing freelance work in photographing senators and congressmen. Called “the camera Girl” and “the Photographer Girl” oftentimes in Washington, Marion Carpenter was feisty and said she refused to be “condescended to by the old men’s club” in the Capitol.

Marion Carpenter also continued to support her mother until the mother died sometime in the 1970s. Marion Carpenter’s pleasures were small and humble. She liked to visit thrift stores where she would sit on used furniture and peruse old magazines, National Geographic with its brilliant photography being a particular favorite. Until the end of her days, Marion Carpenter would show friends photographs from National Geographic and explain why the pictures were composed the way they were.

Beverly Allstop remembered Marion Carpenter as “sensitive, and kind, with an overflowing heart” yet her friend was able to detect a heart that also was brined in bitterness. “She had a heartache and I think it caused her to be a recluse,” Allstop said.

Marion Carpenter did have interests as she aged. She joined the St. Paul Camera Club and showed German Shepherds; apparently, she loved dogs. Miss Carpenter also raced homing pigeons. As she aged, Marion Carpenter rarely ever talked about her past life.

Marion Carpenter’s own life ended at age eighty-two in 2002, bundled in blankets on her sofa to keep warm. Her thermostat was turned down in the arctic Minnesota winter to save money. Alone and quite nearly destitute, Marion Carpenter died alone and forgotten save for her loyal Rottweiler from emphysema. Miss Carpenter’s body was found by friends eventually, yet it remained in the coroner’s morgue while an effort was made to find her son whom she had not seen for more than thirty years.

Finally, an elderly cousin in Maine was located who granted permission for a friend to act as the executor of her estate. Throughout her life, Marion Carpenter had kept her photography equipment, which included more than a dozen cameras. That equipment, along with many of her pictures were sold at an estate sale a year after her death by her son. Mjohn Anderson did donate several of his award-winning mother’s photographs to the Harry Truman presidential library.

In death, newspapers across the country from Maine to Hawaii carried stories remembering Carpenter’s groundbreaking career. Spunky, human and immensely talented, Marion Carpenter was briefly remembered. But then, we never die so long as someone, somewhere still remembers us.