From the author’s personal collection.

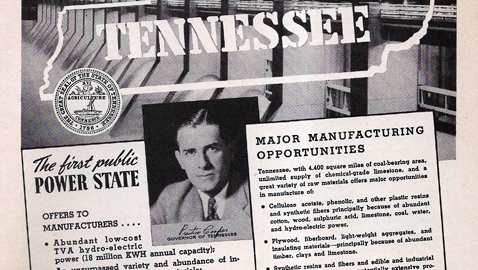

National advertisement featuring Tennessee Governor Prentice Cooper, appearing in TIME magazine, 1943.

The administration of Governor Prentice Cooper, unlike that of his predecessor Gordon Browning, had been relatively quiet. Cooper and Browning were as different in temperament as they were in appearance. Gordon Browning was a big, bluff man with a shock of hair swept back from his forehead with a tendency to being stout, as Browning loved to eat. Cooper was not quite 5’6 and his weight hovered around 145 pounds with a full head of hair meticulously parted and neatly combed. Browning was an excellent speaker, a veteran of the rough and tumble of Tennessee politics, while Cooper’s own speeches were burdened with what some considered to be an excessive use of facts and figures. While Cooper’s speeches might have been educational, they were not exactly exciting.

With an appearance and demeanor much like an accountant, perhaps it was hardly surprising Governor Cooper had managed to bring Tennessee’s budget under control. There was little doubt Cooper would seek a second two-year term in 1940 and once again he was to be part of another “coalition” ticket. This time Governor Cooper would run with Senator K. D. McKellar and Utilities Commissioner Porter Dunlap. Cooper drew an opponent in the form of Knoxville Mayor George Dempster, but the governor clearly did not view Dempster as a significant threat to his reelection.

While Dempster maintained a busy speaking schedule, traveling to most, if not all, of Tennessee’s ninety-five counties, Cooper’s own campaign announced the governor might not even make a single speech in his reelection bid. By the middle of July 1940, only 20,000 pamphlets had been printed in support of the coalition ticket and those were distributed to leaders in each of Tennessee’s counties to be redistributed to voters.

Senator McKellar had no serious opposition of any kind in the primary, opposed only by perennial candidate John R. Neal of Knoxville. Dunlap had been on the Utilities Commission for quite sometime and was expected to easily win renomination in the Democratic primary.

George Dempster, while waging a more conventional campaign, was not exactly setting audiences on fire with his charges that the Cooper administration was dominated by the Crump machine and the governor’s campaign was funded largely through contributions from state employees, a charge Governor Cooper denied.

Dempster’s campaign manager boldly predicted his candidate would go into Shelby County with a majority of the vote. The Cooper campaign snorted at the claim, saying Dempster would not even carry his home county of Knox.

Governor Cooper concentrated on “nonpolitical” appearances and publicity to promote his reelection campaign. Photos of Prentice Cooper shaking hands with movie producer Jesse Lasky, Jr. as Alvin York, an iconic figure in the Volunteer State, signed a contract appeared in newspapers all across Tennessee. The famous Sergeant York was widely admired throughout Tennessee and many newspaper accounts referred to Prentice Cooper as York’s “advisor”. It was an association which clearly did not hurt the governor’s reputation.

Actress Mary Howard, who had appeared in the movie “Abe Lincoln In Illinois”, came to visit Governor Cooper along with her mother at the governor’s mansion on Valentine’s Day. “Abe Lincoln In Illinois” had premiered at Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate and Governor Cooper had met Miss Howard on that occasion and issued an invitation for her to visit the governor’s residence.

The governor used his incumbency wisely, making many visits for dedications and announcements in various Tennessee communities. Cooper was accompanied on several occasions by his Adjutant General of the Tennessee National Guard, Thomas Frazier. Tom Frazier was the son of former governor and U. S. Senator James B. Frazier and the brother of J. B. Frazier, Jr. who was then the U. S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Tennessee.

Prentice Cooper naturally attended the Democratic National Convention that year, along with National Committeeman E. H. Crump, Senator K. D. McKellar and most of Tennessee’s Congressional delegation. Despite denying any interest in a third term, it was obvious to just about every Democrat that Franklin Delano Roosevelt would be renominated. Senator McKellar had already endorsed FDR and while speaking before a caucus of the Tennessee delegates to the national convention, opined that the best choice for vice president was Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Disclaiming any knowledge of whom the President might select as his running mate, McKellar expressed confidence that Roosevelt would choose the stately Hull for the vice presidential nomination.

One thing was certain; FDR’s incumbent Vice President, John Nance Garner of Texas, was going home to Uvalde. Disgusted with the notion of a third term for any man, Garner had tried to compete with Roosevelt for the presidential nomination in 1940 without success. Senator McKellar concluded even if FDR did not pick Hull as his running mate, there were other qualified Tennesseans for the place, “including Mr. Crump”.

The Memphis Boss, while enjoying the compliment, dismissed the notion he would allow his name to be placed before the convention. The Tennessee delegation, like many gathered at the convention, were horrified when President Roosevelt chose Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace as his running mate. The convention quite nearly rebelled at the notion of nomination Wallace, who had been a Republican most of his life, and FDR had to threaten to refuse the presidential nomination if the delegates did not accept his choice.

Back home in Tennessee, Governor Cooper’s election strategy worked beautifully as he crushed George Dempster in the Democratic primary. Cooper had won a second term and as he approached the end of that term, the United States was deeply embroiled in the Second World War.

Prentice Cooper, under Tennessee State law, could seek another two-year term as governor, although no incumbent had won a third consecutive term in almost one hundred years. Cooper was eyeing the Senate seat held by Tom Stewart, who would be up for reelection that same year. Governor Cooper’s senatorial ambitions were apparently stifled by K. D. McKellar. Senator McKellar enjoyed an excellent working relationship with Stewart who was largely content to follow McKellar’s lead on most issues. Cooper was also close to Senator McKellar and when E. H. Crump began grumbling that the state administration was being unfair to Memphis and Shelby County, it was McKellar who approached the governor to work things out.

When it became readily clear Senator McKellar would not support Cooper for the Senate, he opted to seek a third term as governor in 1942. Cooper’s path to reelection that year was more complicated, as he drew a serious opponent in J. Ridley Mitchell. Mitchell had served in the Congress from 1931-39, giving up his seat to run a quixotic race for the U. S. Senate in 1938. Despite having run third in the 1938 Senate race, Mitchell had made a very strong showing in his native Middle Tennessee.

The contrast between Prentice Cooper and J. Ridley Mitchell could not have been greater; Mitchell was tall, bald, and distinguished. The former Congressman was also a very good speaker and possessed a demeanor one expects of a successful politician. His successor in Congress, Albert Gore, Sr. described Mitchell as the sort of politician who could promise every constituent a new post office and then make them happy when the promised post office never materialized. Prentice Cooper was diminutive, short tempered, with a full head of carefully combed hair. Cooper was not necessarily a good stump speaker, nor was he overly impressive, although he was clearly a good administrator.

Former Congressman Mitchell had offered himself as the “harmony” candidate during the 1938 senatorial election, the only position left in the war between the McKellar – Crump axis and that of Governor Gordon Browning’s state machine. To run against Governor Cooper, Mitchell reinvented himself as an opponent of the Crump organization.

Cooper officially announced his reelection bid on April 17, 1942; Ridley Mitchell followed suit the very next day. Both Cooper and Mitchell promised to end the poll tax if elected. Mitchell, true to form, had something for everyone in his platform. The former Congressman said he recognized the deficiencies in Tennessee’s educational system and promised to bring about needed reforms. Mitchell said he would strongly support the TVA and would closely adhere to the “business-like” principles of former Governor Gordon Browning in terms of not only expenditures, but personnel as well.

In his announcement he was running for governor, J. Ridley Mitchell directly challenged Crump, saying the Memphis Boss wanted to keep Prentice Cooper in office to maintain his control of the state. Mitchell said his election would save the people of Tennessee from the “tyrannical dictatorship” of E. H. Crump.

Mitchell’s candidacy did not afford Governor Cooper the luxury of running a casual campaign. Prentice Cooper was soon forced to campaign hard, as Tennesseans had proven to be reluctant in granting an incumbent governor a third consecutive term. For the third time, a “coalition” ticket was formed, consisting of Cooper for governor, Tom Stewart for U. S. Senate and Leon Jourolman for Utilities Commissioner. Senator Stewart was himself facing a determined challenge from Edward W. “Ned” Carmack, son of the slain former Senator Edward W. Carmack.

The war was not going well for the allied forces in 1942 and voters were restive. Many incumbents all across the nation would face defeat in the election that year. Mitchell’s campaign bought ads in Tennessee newspapers underscoring the theme of freedom, asking voters, “We are fighting a war for freedom, why not vote for that same freedom?” Mitchell’s ads urged voters to “Beat Dictator Crump!”

Not surprisingly, Mitchell soon received an endorsement from former Governor Gordon Browning. Since leaving office in 1939, Browning had returned home to Huntingdon, Tennessee. Browning had been elected Judge of the Chancery Court, a position that had been occupied by another former governor, Tom C. Rye. With Rye’s retirement, Browning was elected to an eight-year term in 1940.

Browning’s endorsement of J. Ridley Mitchell was his first foray into state politics since his humiliating defeat by Prentice Cooper in 1938, a fact Browning himself mentioned during his speech at McKenzie, Tennessee. Browning’s praise of Mitchell drew a quick response from E. H. Crump who dismissed the former Congressman as “a professional office-seeker”. Crump pointed out Browning’s decrying dictatorship after his own bid to impose a county-unit plan and disenfranchise voters as well as control the state’s election machinery was hypocritical. Crump sniffed that no intelligent voter could trust Browning’s “head, his heart or his hand”. The Memphis Boss said that both Browning and Mitchell objected to the fact Governor Cooper had provided the people of Tennessee with an honest and efficient government.

The battle for Prentice Cooper’s third term was well under way.