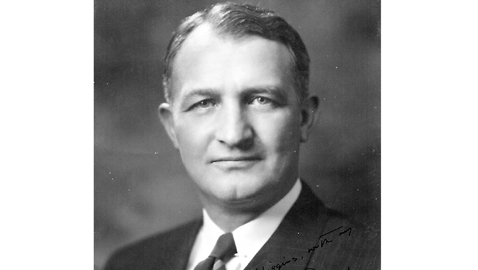

From the author’s personal collection.

Autographed photo of Senator Chapman Revercomb of West Virginia

By Ray Hill

West Virginia was once one of the more reliably Republican states in the country. Following the Great Depression and the rise of the machine headed by U. S. Senator Matthew Mansfield Neely of Fairmont, the election of 1932 changed the political landscape in West Virginia. Herman Guy Kump was elected governor in 1932 and he began building a state machine that would eventually rival the federal machine of Senator Neely.

For the next two decades the only Republican who managed to have real statewide appeal was a lawyer named William Chapman Revercomb. Born July 20, 1895, in Covington, Virginia, Chapman Revercomb attended public schools until he went to Washington and Lee University. Revercomb interrupted his education to serve in World War I before returning home to get his law degree from the University of Virginia.

Chapman Revercomb practiced law for a time in Covington, but moved to Charleston, West Virginia where he maintained a law office until his death. Revercomb was a successful and accomplished lawyer and became interested in Republican politics. Revercomb made a bid for the GOP gubernatorial nomination in 1936, but was unsuccessful.

Revercomb continued to work for and support Republican candidates in West Virginia until he again decided to seek office himself. Revercomb became a candidate for the United States Senate in 1942 and faced formidable opposition in the person of Raymond Funk, a wealthy businessman. Funk spent lavishly on his campaign, but lost narrowly to Revercomb.

While the Republicans were fighting it out, the Democrats were waging a bitter battle of their own.

Matthew M. Neely had run for governor in 1940 to destroy the statehouse machine in West Virginia established by Governor H. Guy Kump. Neely resigned his seat in the United States Senate and even managed to appoint his own successor. Both Neely and his predecessor as governor, Homer Holt, had appointed senators and the United States Senate had to determine which was the legitimate senator.

By 1942, Neely had replaced the old statehouse machine with his own appointees and was ready to return to the United States Senate. He faced former Governor Kump in the primary, as well as former U. S. Senator Rush Holt, once Neely’s protégé and then his bitter enemy. Neely won the Democratic nomination and confidently expected a triumphant return to the Senate.

Neely was shocked when he lost to Chapman Revercomb. It was a huge upset and Revercomb was the first Republican to be elected to the United States Senate from West Virginia since 1928. Revercomb remains to this day the last Republican elected to the U. S. Senate from West Virginia.

Revercomb certainly had the classical appearance of a senator and was highly regarded by his colleagues. Reasonably conservative, Revercomb was also an ardent supporter of civil rights, yet his first time in the United States Senate was to be plagued by a topic familiar to many Americans today: immigration.

The Republicans had won control of both Houses of Congress in 1946 and Revercomb brought his “displaced” persons bill, which was in essence an immigration bill. Liberals across the country were appalled by the bill and denounced it as too restrictive.

The controversy surrounding the displaced persons bill was still raging when Revercomb was seeking a second term in 1948. The old war horse of the Democratic Party in West Virginia, Matthew Neely, was making yet another of his irrepressible comebacks.

Defeated by Revercomb in 1942 and ineligible to seek a second term as governor in 1944, Neely had run for his old Congressional seat in 1944 and was elected, only to lose in the 1946 Republican landslide. Seventy-four years old in 1948, Neely was pressing Senator Revercomb hard.

The Republican presidential nominee, New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey, was so confident of his own election that year, he believed he had the luxury of interfering in state races and pointedly refused to endorse Revercomb for reelection. During an appearance by Dewey in West Virginia the presidential campaign, Senator Revercomb was all but ignored.

1948 was a very good year for Harry Truman, but a poor year for Republicans. President-In-Waiting Thomas E. Dewey received the shock of his life, along with every pollster and political prognosticator in the country. The Republicans lost control of the Congress and Chapman Revercomb lost decisively to Matthew Neely.

Revercomb returned to his law practice and remained one of West Virginia’s preeminent Republicans. He bided his time and in 1952 announced he would challenge West Virginia’s other Democratic senator, Harley Kilgore. Revercomb thought the prospects of returning to the United States Senate were favorable with highly popular General Dwight D. Eisenhower at the top of the ticket. Former Democratic U. S. Senator Rush D. Holt had changed parties and was making a strong race for the governorship.

Revercomb waged the most unusual campaign of his entire career in 1952, stressing Communism and Senator Kilgore’s liberalism. Wisconsin demagogue Joe McCarthy was then at the height of his powers that year and many campaigns across the country gave the voters a taste of McCarthy’s rhetoric.

In West Virginia, it did not work.

Revercomb in fact trailed the rest of the GOP ticket; Eisenhower barely lost West Virginia, tallying 48% of the vote. Rush Holt came mighty close to winning the governorship and may have actually won save for some tampering with the election returns.

Once again defeated, Revercomb resumed the practice of law.

On February 28, 1956 Senator Harley Kilgore died. There would be a special election that year to fill the remaining two years of Senator Kilgore’s term and Governor William Marland signaled his intentions when he appointed a caretaker to fill the vacancy caused by Senator Kilgore’s death.

Marland became a candidate for the U. S. Senate, but his popularity within his own party was low and lower still with the general public. Marland’s term had been controversial and Revercomb sensed an opportunity and announced he would again be a candidate for the Senate. Revercomb’s standing with his fellow Republicans was slipping, as he encountered serious opposition inside his own primary.

Demonstrating he was still the most personally popular Republican in West Virginia, Chapman Revercomb won the GOP primary handily.

1956 was to be the best year for Republicans in West Virginia since the advent of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal. Cecil Underwood, a thirty-two year old state legislator, was the GOP nominee for governor. Young, handsome and an able speaker, Underwood was a surprisingly strong candidate. The Democratic nominee, Congressman Robert Mollohan, the personal choice of Senator M. M. Neely, was hit during the general election for several scandals and considering William Marland was already unpopular, it made the Revercomb and Underwood ticket especially appealing.

President Eisenhower carried West Virginia in 1956 and both Cecil Underwood and Chapman Revercomb won their respective elections for governor and the United States Senate.

Chapman Revercomb returned to the U. S. Senate and his second term was considerably less conservative than his first. Revercomb was perceived as an “Eisenhower” Republican. Revercomb, highly energetic and a hard worker, redoubled his efforts, realizing he had to run again in 1958 for a full six-year term.

The political situation in West Virginia was complicated by Matthew Neely’s death from cancer in January of 1958. Governor Underwood appointed John D. Hoblitzell to the Senate and Hoblitzell would have to run in the fall election with Chapman Revercomb.

Unlike 1956, West Virginia Democrats did not make the mistake of fielding weak or controversial candidates. Former Governor William Marland attempted a comeback, but lost the primary. The two Democrats nominated to run for both Senate seats were former Congressman Jennings Randolph and Congressman Robert C. Byrd.

Revercomb would face Robert Byrd in the general election and the incumbent senator had to bear the additional burden of a national recession, which had hit West Virginia particularly hard.

Despite an energetic campaign, Revercomb lost to Byrd, who would go on to become legendary in his own right and serve in the United States Senate longer than any other individual. Senator Hoblitzell, trailed Senator Revercomb in the balloting and lost to Jennings Randolph.

Revercomb went home to Charleston and practiced law and earned a substantial fee by representing one of his former colleagues in the United States Senate. Edward V. Robertson, born in Wales, had moved to Wyoming, where he became a wealthy rancher. Robertson hired Revercomb to represent him in a lawsuit and the former senator was well paid for his efforts.

Revercomb had been considered for appointment as a federal judge, but his candidacy was undermined by his former colleague John Hoblitzell and the Cecil Underwood faction of West Virginia’s Republican Party, who complained Revercomb was too old. In an interesting twist of fate, Revercomb would outlive Hoblitzell by more than a decade.

In 1960, Chapman Revercomb made his last race for statewide office. Revercomb had every reason to believe he still retained his popularity with his fellow Republicans who had nominated him five times for the United States Senate. Revercomb ran for governor to succeed Cecil Underwood, who could not run for a second term. Underwood was himself running for the United States Senate and it is puzzling to consider just why the governor felt constrained to make an endorsement in the GOP primary for the gubernatorial contest. Underwood made a dramatic announcement he was endorsing Harold Neely, a minor official in the Underwood administration, over former Senator Revercomb.

Revercomb lost the nomination and Underwood lost the general election. Underwood would go on to run for statewide office numerous times and his opposition to Senator Revercomb was not forgotten by many loyalists and it took Underwood forty years to finally win another election.

Senator Revercomb returned to his law practice and remained one of West Virginia’s elder statesmen. Urged to run for the State Supreme Court in 1964, Revercomb declined, still fearful the Republican Party in West Virginia was too divided.

Chapman Revercomb died October 6, 1979. Had he lived just a little longer, he would have seen his son elevated to a federal judgeship by President Ronald Reagan.

Chapman Revercomb remains perhaps the most enduringly popular Republican in the Mountain State during modern times.