Knoxville’s Lawyer & Statesman: Hobart F. Atkins

By Ray Hill

Like all things, Hobart Freeman Atkins long ago passed into the pages of history. And like so many others, Hobart F. Atkins deserves to be remembered. When he died, the Knoxville News-Sentinel remembered him as, “A Union County boy, who came to Knoxville at an early age and made a name for himself in the legal, legislative, construction and war service fields. . .” It was no overstatement for Hobart Atkins had served four terms in the Tennessee State Senate and as an attorney had played a crucial role in “winning one of the U.S. Supreme Court’s most historic decisions.” A bachelor, Hobart Atkins never married and lived in a remarkably modest one-bedroom, one-bath home.

It would be accurate to say Hobart F. Atkins was a character in his own right. The News-Sentinel phrased it differently, saying Atkins had “a personality all his own – – – earthy and droll.” Atkins was indifferent and downright careless in his personal appearance. Hobart F. Atkins apparently was out to impress nobody and his head of hair was unruly and all too often “unkempt.” Throughout his life, Atkins “retained his hillbilly brogue.” Yet that same “hillbilly brogue” masked a fine legal mind and he frequently addressed courtrooms and juries by quoting Abraham Lincoln. Atkins frequently said he had no higher aspiration “than to be a lawyer of the Lincoln type.”

Hobart Atkins had first come to Knoxville from Union County in his teens. He had served in the Navy during the First World War and attended the University of Tennessee and was licensed to practice law in 1921. Even to the time he died, Atkins was “lean and rugged with a tanned and wrinkled face.” The weathered state senator’s favorite recreation was bowling. When once asked why he ran for public office, Hobart Atkins replied he believed “a fellow has a duty to help make the country a little better if he can.”

As to his politics, like his hero, Abraham Lincoln, Hobart Atkins was a Republican. Atkins ran for Congress in the 1948 GOP primary against Congressman John Jennings Jr. and won roughly 47% of the vote.

In 1952 and 1958, Hobart Atkins was the Republican nominee for the United States Senate at a time when the GOP was a distinct minority in the Volunteer State. While running as the GOP nominee for the U. S. Senate in 1958, Atkins was also the Republican nominee for a seat in the Tennessee State Senate. The country was in a recession that year and it was not a good electoral year for Republicans who lost thirteen seats in the U.S. Senate. Hobart Atkins lost both races. When first elected to the state Senate, Atkins’ district was comprised of Knox, Anderson, Loudon and Roane counties. His subsequent three races were centered in Knox County.

When Hobart Atkins ran his dual campaigns for the United States Senate and the Tennessee State Senate, he never had any illusions about winning a statewide race; however, he had a reasonable expectation of winning the race for the state Senate. Atkins’ opponent was Charles T. Eblen, who had served a term in the House of Representatives from 1954-1956. Eblen was a credible challenger and while Atkins carried Knox County, his campaign was hampered by the fact he was confined to the hospital during the latter part of the race. Charles Eblen won, having carried Anderson, Roane, and Loudon counties.

Warren Webster, campaign manager for the GOP ticket in Knox County, had urged Knox Countians to vote for Atkins twice, but his admonition was ignored. It was a Democratic year and Senator Albert Gore carried Knox County by over 10,000 votes. Democrats had been shut out of the 1956 legislative races in Knox County but also won both of the state senate seats up for election in 1958. State Representative Ralph Adcock was defeated unexpectedly as well. Democrats also won most of the offices up for election locally in Knox County, sweeping much of the courthouse.

Hobart Atkins was a lawyer’s lawyer and unlike some of the more squeamish and discerning of his colleagues at the Bar, the senator believed even the guilty and disreputable deserved good legal representation. Atkins kept up a lively criminal defense practice and represented some who were downright notorious. Atkins was the defense attorney for the Touhy Brothers, one of whom had been framed for the kidnapping of John “Jake the Barber” Factor, brother of cosmetics magnate Max Factor. Being from East Tennessee, Hobart Atkins represented his fair share (and more besides) of moonshiners, bootleggers and rumrunners. Atkins frequently represented the dregs of society, oftentimes without charging a fee for those in economic dire straights.

During the 1957 session of the General Assembly, Senator Hobart Atkins announced he would not support the gubernatorial administration’s segregation bills, which were contrary to the recent decision of the Supreme Court of the United States. Atkins said the issue of segregation “must be met as a moral question, not as a legal one.”

Atkins’ popularity with Republicans had not flagged, as he won the Republican nomination for state senator over veteran lawyer and politico Judd Acuff easily in 1960. Atkin faced T. M. “Ted” Coulter in the general election. Coulter had first been elected in the 1958 Democratic sweep and was generally considered to be a representative of organized labor as he was an employee of the railroad. Unlike 1958, 1960 was not a Democratic year. Vice President Richard Nixon won more than 60% of the ballots cast in Knox County while Hobart Atkins won a comfortable victory over Senator Coulter. Perhaps one of the more notable victories of that particular election was that of Mrs. Katherine Shook, a Democrat, who ran first in the county-wide race for State Representative. Mrs. Shook was a former teacher in the city school system and a leader in the local League of Women Voters. Katherine Shook had been elected as a delegate to the 1959 Constitutional Convention for the State of Tennessee.

In 1962, the congressman from Tennessee’s Second Congressional District was Howard H. Baker, father of the U.S. senator of the same name. Baker was also the chairman of the Tennessee State Republican Executive Committee at the time and he sent a telegram to state Senator Hobart Atkins from Washington, D. C. to praise his friend for Atkins’ continuing battle for reapportionment in the Volunteer State. “Congratulations on a great victory,” the wire began when the U. S. Supreme Court ruled the state legislature had failed to properly guard the rights of voters through redistricting and was indeed a matter for federal courts to decide. Congressman Baker told the Knoxville Journal, “I congratulate Sen. Hobart Atkins who has worked so long and effectively to bring about constitutional reapportionment.” It had been a winding and torturous route for Hobart Atkins who demonstrated remarkable persistence in pursuing his goal with dogged determination. Five times Senator Atkins had drafted bills calling for reapportionment; the bills went exactly nowhere. Only East Tennessee Republicans had voted for his bills.

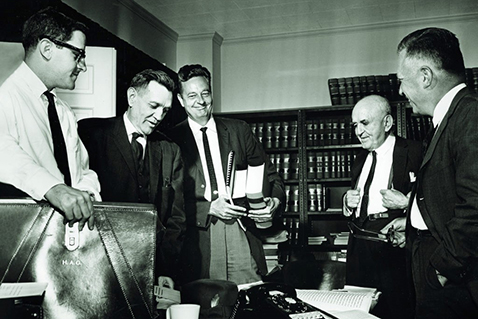

Ultimately, Hobart Atkins did what lawyers do: he filed a lawsuit. Along with former congressman and mayor of Memphis, Walter Chandler and Charles S. Rhyne of Knoxville, Hobart Atkins represented ten taxpayers from Shelby, Davidson, Knox, Hamilton and Montgomery counties. That was the beginning of what became Baker v. Carr, which began in 1955. Senator Atkins had the pleasure of witnessing some 4,000 Knox Countians sign their names to a petition urging him to seek reelection in 1962. The petitions were being circulated by a nonpartisan group and the language included in the petition referred to Hobart Atkins as “one of the few statesmen we have left.” Guy Smith’s Knoxville Journal published an editorial stating Atkins deserved to have no opposition in his bid for reelection, although the newspaper acknowledged the senator had not decided whether or not he would run again. The Journal readily acknowledged the legislator was not in the “most robust” of health and his recent service had been “a great drain upon his strength.” Smith’s editorial stated ordinarily the Journal would not have intruded and questioned Atkins’ own preference to retire from the Tennessee General Assembly, but the editor thought the senator serving in Nashville had to “be classed as a public necessity.” One of the most popular Democrats in Knox County, Charles C. Spangler, the elected highway commissioner, announced he was running. Sensing the political mood in Knox County, Spangler later dropped out. Hobart Atkins was reelected without opposition. At that time, state senators were elected every two years and Atkins had no opposition when he sought another term in 1964.

For years, Hobart Atkins had been plagued by emphysema. The senator was also afflicted with an asthmatic condition which made it impossible for him to climb a flight of stairs without stopping to catch his breath. According to the Knoxville News-Sentinel, Senator Atkins kept an “inhalator on his desk in his office” when he felt the need to use it. Atkins was remembered for never allowing the state of his health to darken his own view of the world, remaining cheerful and never complaining. During both the 1963 and 1965 sessions of the Tennessee General Assembly, Senator Atkins was stricken with respiratory ailments which required him to leave Nashville and come home to Knoxville and go into the hospital.

Hobart Atkins slipped away at St. Mary’s Hospital without knowing of his final and most lasting achievement as both an attorney and a legislator: the ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States in the case of Baker v. Carr. Long an advocate of urban areas having the representation required by population, Atkins passed without knowing of his ultimate success. Atkins’ death was much editorialized in Tennessee; the Johnson City Press-Chronicle thought the loss of Atkins to East Tennesseans was “substantial.”

The Knoxville News-Sentinel lamented the irony, “Hobart Atkins’ death comes at the very hour of his final triumph in the most creditable effort of his long and varied career.” The editorial noted Atkins’ “fight for equitable apportionment of both Legislative and congressional seats has virtually been won.” Because of Baker v. Carr, the Knoxville News-Sentinel editorial believed Hobart Atkins’ “name will be remembered in history for that.” “It was a victory for justice and fair play, righted a wrong that Tennessee Legislatures had been compounding for half a century by failing to reapportion every ten years as the Constitution requires.” The News-Sentinel acknowledged Hobart Atkins was “a self-made man” and noted his success as both a businessman and an attorney. So, too, did the editorial recall Hobart F. Atkins as a kindly man, who unselfishly oftentimes financially assisted those who needed help.

Guy Lincoln Smith, editor of the Knoxville Journal, the voice of Republicanism in the State of Tennessee, had been a personal friend of Hobart Atkins. Smith described Atkins as “one of the greatest and most valuable men of our time. He will go down in history as one who revolutionized and bettered our whole legislative system – – – not just our state, but in our country.”

The Memphis Commercial Appeal acknowledged Hobart Atkins never found “the statewide political popularity which he once sought.” Instead, what Atkins found was “esteem” from friend and foe alike.

The Nashville Tennessean editorialized Hobart Atkins as “one of the state’s more outstanding legislators,” noting the senator had won a well-deserved “reputation for independence and tenacity in upholding Republican principles in the face of temptation for compromise.”

The editorial printed in the Knoxville News-Sentinel concluded, “Mr. Atkins ended his career as a statesman. So few who engage in politics ever really attain that distinction.”

A throng of hundreds of people gathered at the funeral of Senator Hobart Atkins to say farewell to a man who had made a difference, including Governor Frank Clement. The Reverend Willis R. Allen said of Atkins, “This man left his footprints in the sands of time.”

And so he did.