The Gentleman From Mississippi

William M. Colmer

By Ray Hill

William Meyers Colmer is one of the longest-serving members of the U.S. House of Representatives in Congress. Colmer was elected to the House at a time when Southern states were ruled by one party and Southerners had a habit of reelecting an incumbent continuously so that he could acquire seniority and influence and better serve his district and state. Some called it the South’s revenge for having lost the Civil War. Colmer served in the House of Representatives for 40 years. By the time Bill Colmer left office, he had served in Congress longer than any other Mississippian. Colmer served through the Second World War, as well as the Korean and Vietnam wars. Colmer served in the House during the Great Depression, which was bitterly intense in the Magnolia State.

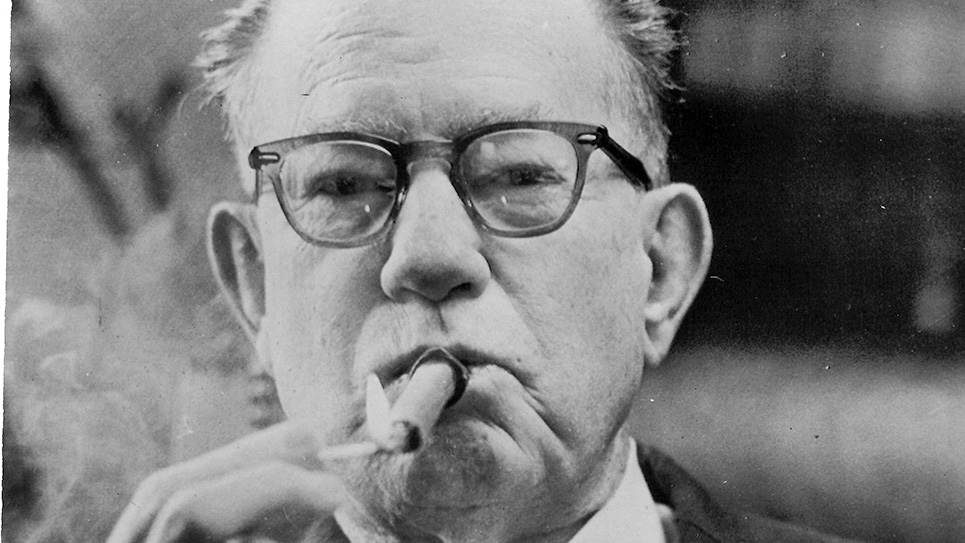

Mild-mannered, redheaded and bespectacled, William Colmer looked like a reasonably prosperous lawyer, which is what he was. “A dour, gangling man with a choppy gait, Colmer looks younger than his 70 years,” a writer for TIME wrote in 1961. The congressman’s name was pronounced as “calmer.” Colmer was a man who evidently never forgot his humble beginnings and unlike many of his contemporaries, there was nothing flamboyant about William M. Colmer. One newspaper editor, eulogizing Colmer after his death, recalled the congressman was not afflicted with the “overwhelming ego which seems such a major part of so many of today’s politicians.” Colmer was remembered by friends and foes alike as a man of integrity and was always paid the accolade of being a “gentleman.”

Colmer had been county attorney and district attorney before challenging incumbent Congressman Robert S. Hall. Hall had been elected to two terms in the House before being challenged by Bill Colmer. In 1932, there was a free-for-all inside the Democratic primary with Colmer, Congressman Hall and former Congressman T. Webber Wilson all seeking the nomination. All three candidates ran a close race, within 1,235 votes of one another, with a fourth, lesser candidate siphoning off a couple thousand votes. Colmer and Congressman Hall faced each other in the run-off election, which the district attorney won decisively. Two years later, Congressman Colmer beat back the challenge of three other Democrats to win the Democratic primary. Only once, in 1966, did Colmer’s vote in the Democratic primary ever dip below 60% and that year it was just by a fraction.

In a day and time when the racist label is thrown about casually, William Colmer was a staunch segregationist. Representing the Pascagoula area in the House, Colmer became quite an expert in servicing his constituency. TIME magazine, the premier news magazine of its day, was, like its publisher, steadfastly internationalist in its point of view. Colmer was, by the 1950s, becoming skeptical about the billions of dollars Congress was spending annually on foreign aid. TIME sniffed that Congressman Colmer was an “arch-reactionary” as the Mississippian snapped, “We have seen only in the last few days instances of the fact that this aid is not only not appreciated, but in many instances is not welcome.” Colmer was one of several congressmen who offered amendments to pending legislation that would have had the effect of gutting the very “principle of foreign aid.”

When first elected to Congress, Bill Colmer ran as a loyal supporter of Democratic presidential nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt. Colmer was elected in 1932 and participated in the first hundred days of Roosevelt’s New Deal, which the Mississippian supported. When Roosevelt was in New Orleans, Congressman Bill Colmer made the trip from his district to see the president. “I’m proud of Bill Colmer and what he has done for the Roosevelt Administration,” FDR said. As the New Deal began to ebb, so did Congressman William Colmer, who became more conservative with the passage of time. At the end of his long life, few could recall Colmer had been an enthusiastic New Dealer at one time. Colmer readily acknowledged the fact, drawling to a friend once, “You may not believe it, but I came to Washington as something of a liberal.”

Only once did William Colmer attempt to seek a promotion when he ran in a 1947 special election following the death of Senator Theodore Bilbo. When he first announced his candidacy for the Senate, Bill Colmer was considered the favorite to succeed Bilbo. Congressman Colmer ran in a crowded Democratic primary, but he ran second to winner John C. Stennis, who had been a judge of the Circuit Court. Never again did Bill Comer ever try to win higher office, remaining content to serve his district in the House of Representatives.

By the decade of the 1950s when Colmer had been in the House of Representatives for 20 years, he was a high-ranking member of the Rules Committee, which was enormously powerful as it could bottle up bills or send them to the floor. Colmer and the chairman of the Rules Committee, Howard W. Smith of Virginia, proved to be quite efficient at obstructionism, smothering to death any number of Civil Rights bills. When John F. Kennedy became president of the United States, he realized something had to be done about the House Rules Committee, which was a roadblock to much of the legislation his administration wanted passed. Kennedy enlisted the aid of the most influential member of the House, Speaker Sam Rayburn. In the last big brawl of his lengthy career, Rayburn fought a brutal hand-to-hand contest with Judge Smith, Colmer and their supporters to enlarge the membership of the two committees with two additional Democrats and one Republican. The speaker figured that would give the Kennedy Administration a margin of one. Eventually, realizing they didn’t have the necessary votes to win inside the Democratic Caucus, Rayburn was finally successful in fending off an assault by a combination of conservative Democrats and Republicans.

In 1966, following the defeat of Judge Howard W. Smith, William M. Colmer of Mississippi became chairman of the Rules Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives. Colmer once described the function of the House Committee on Rules as a “cooling off vehicle, especially in a time of great national excitement, distress and emotion.” House Democrats, with a substantial majority, in 1949 adopted a rule that limited the Rules Committee’s ability to hold a bill to 21 days. Two years later, a coalition of conservative Republicans and Democrats were able to repeal the rule.

Throughout his long tenure in the House, William M. Colmer had bolted the regular Democratic Party to support tickets that were more popular locally. Like most everyone in Mississippi, Congressman Colmer had refused to back Harry Truman in 1948, preferring to support the States’ Rights or “Dixiecrat” candidates, Strom Thurmond and Fielding Wright, who was the governor of Mississippi. In the 1960 election, Mississippi supported an independent slate of electors rather than regular Democratic nominee John F. Kennedy. Some Democrats rumbled Colmer should be punished for his political apostasy by being removed from the Rules Committee or stripping him of his seniority. The idea went nowhere.

Colmer annually held a banquet, which drew presidents of the United States as guests, as well as fellow congressmen and senators. The feast served Mississippi’s seafood.

As is usually the case with an aging incumbent, for the last decade of his service in the House, rumors seemed to float every two years the congressman was going to retire. Colmer became increasingly sensitive about his advancing age, insisting his age not be stated in the Congressional Directory. Colmer finally made the announcement he would not seek reelection at age 82. When Colmer decided to retire in 1972, he surprised some by endorsing his administrative assistant, Trent Lott, who was running as a Republican. Lott had been a conservative Democrat previously, but he felt could win the general election as the nominee of the GOP. Colmer contacted his loyal supporters and financial backers on behalf of Lott.

Trent Lott won the election as Richard Nixon swamped George McGovern in Mississippi and became one of two GOP congressmen elected from Mississippi, the other being Thad Cochran.

The eight years of retirement for William M. Colmer were pleasant. In spite of his advancing years, Colmer was apparently in good health and continued to be seen inside his former district and was on hand for any number of public appearances. When Vice President Gerald Ford came to Hattiesburg to campaign for GOP Congressman Trent Lott, the former congressman sat on the dais reserved for special guests. It was Bill Colmer, Ford’s longtime former colleague, who introduced the vice president to the audience.

In 1974, the new federal building in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, was named in honor of former Congressman William M. Colmer. The dedication ceremonies honored Colmer who spoke to the audience after being introduced by his successor in the House, Trent Lott. “If they’d listened to Bill Colmer 25 years ago, we wouldn’t be in the mess we’re in today,” Lott said. Following the result of the 1974 elections, which saw the number of Democrats in Congress increase due to the backlash against Watergate and President Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon, Colmer sighed, “I do not think there is any escaping the fact that the new Congress is going to be overwhelmingly on the liberal side.” The former congressman worried the increased Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress would be perceived by the “liberals” as “a mandate from the people to spend more.”

Although the former congressman was suffering from a cold, a reporter for the Biloxi Sun–Herald said Colmer was still quite articulate, saying the country’s “biggest problem” was inflation. “I do not think we can go on indefinitely with deficit spending without bringing down the house of inflation on us.” “We must either stop inflation or we are going to lose our cherished form of government,” Colmer warned.

In retirement, Colmer endorsed his friend and former colleague Gerald Ford for president in the 1976 election and continued to enthusiastically support his former aide and protégé, Trent Lott. Colmer explained Ford not only had “moral integrity” but was also a man of fundamentally sound conservative principles while his own party advocated “socialist” ideas which had long been repudiated by Mississippians at the ballot box. When former Texas governor and Nixon Cabinet officer John Connally came to Mississippi to attend a reception for Lott, former Congressman Bill Colmer quite nearly “stole the show” with his own remarks. The nearly 350 guests gave Colmer such a warm reception, he quipped, “I never would have supported this errand boy” for Congress had he known so many people were supportive of him. Colmer referred to his former aide as “a pretty good boy” who had been “flirting with this job for some time now.” “With the record Trent has made, I have no fear he will be elected,” Colmer added. John Connally said, “If all the Democrats in this country had been like Congressman Colmer, I wouldn’t be a Republican.”

Colmer joined President Ford on a trip down the Mississippi River, along with former GOP Congressman Prentiss Walker and former Governor John Bell Williams. Colmer told a reporter he had supported every Democratic presidential nominee until he left Congress. “But I’m just one of thousands of Democrats who are going to vote for Ford,” Colmer said. Former Governor and Congressman John Bell Williams acknowledged what many already suspected, saying he had not supported a Democratic presidential candidate since 1952. “And I wasn’t too proud of that,” Williams lamented. As to his endorsement of Gerald Ford, John Bell Williams said, “I don’t think it will come as a surprise to anyone who knows my independence.” A total of four former Democratic congressmen from Mississippi announced they were voting for President Ford: Colmer, Williams, Thomas Abernethy and Charles H. Griffin.

Time takes its toll on the healthiest and most vibrant of people and Colmer was no exception. The last month of his life, Colmer’s health began to seriously fail. Bill Colmer was quite simply worn out and he died at age ninety.

© 2024 Ray Hill