D. Worth Clark of Idaho

David Worth Clark was something of a political wunderkind in his day, first winning election to Congress at age thirty-two. While he only served a single term in the United States Senate, it was during one of the most critical times in American history. D. Worth Clark came to the U.S. Senate just as the Second World War was about to erupt and he left that august body as the war was coming to a close. Indeed, the rise of the aggression of the Japanese Empire in the Far East and the bellicose ambitions of Germany’s Adolf Hitler worried millions of Americans. Those worries helped to propel D. Worth Clark into the United States Senate. Idaho was the same state that kept William E. Borah, “the Lion of Idaho,” in the U. S Senate from 1907 until his sudden death on January 19, 1940. Borah was one of the most fervent of the many prominent members of the Senate who opposed an interventionist foreign policy. Borah, a Republican, proved to be impregnable at the polls, winning in the solidly Democratic year of 1936, easily beating Governor C. Ben Ross in the general election. Like Borah, D. Worth Clark was profoundly against internationalism, earning him the sobriquet of “isolationist.” The truth of the matter is most Americans were at heart isolationists, as very few wished to involve their country in another world war.

Politics likely ran through D. Worth Clark’s blood; it certainly did through the family bloodline as two of his uncles, Barzilla Worth Clark and Chase Addison Clark, served a term as governor of Idaho. Worth Clark’s cousin Bethine, daughter of Governor Chase Clark, married Frank Church, who would represent Idaho in the U.S. Senate for 24 years. D. Worth Clark did not hold on to the shirttail of his uncles, as he had already been elected to the House and Senate as his uncles reached the governor’s mansion.

A compact man with wavy hair and piercing eyes, D. Worth Clark was a native of Idaho, having been born in Idaho Falls. A superlative student, Clark graduated from the University of Notre Dame and went on to Harvard Law School, turning down a Rhodes scholarship to attend. With the ink on his law degree barely dry, D. Worth Clark went home to Idaho, settling in Pocatello where he began the practice of law. As with many beginning lawyers, Clark accepted a position with a government agency to learn his craft. For about two years, Worth Clark worked as an assistant state attorney general before resigning in 1934. The attorney general, cigar-smoking Bert H. Miller, would later follow D. Worth Clark to the United States Senate.

Clark’s resignation from the Idaho Attorney General’s office was due to the death of Congressman Thomas Coffin. Only 47 years old, Coffin had been hit by a car while walking on the grounds of the Capitol. A few days later, Congressman Coffin died from his injuries. When announcing his campaign for Congress to serve Idaho’s Second Congressional District, Clark declared, “My platform is simple. I shall support Roosevelt in his recovery program, but I shall always vote as the interests of Idaho demand.” That caveat would remain in place throughout D. Worth Clark’s political career.

Clark did not have an easy time of it inside the democratic primary. The death of Tommy Coffin had caused no less than fifteen candidates to file for the primary. The Idaho Statesman thought Clark and Judge Robert M. Terrell and Lewis Williams, Idaho’s Commissioner of Welfare, were the leading candidates, but each of the other candidates seemed to have pockets of support inside the Second District and there were another four candidates “so closely bunched right behind” and the seven remaining candidates made it anyone’s guess as to who the nominee would be.

Worth Clark gained traction orating in small towns and hamlets and medium-sized cities, bellowing “no Idaho river should run to the sea as long as an Idaho farmer needs water.” Clark won the Democratic nomination to face Republican Heber Q. Hale in the general election. The fall campaign saw Clark continue his energetic campaign throughout the district. The general election was anticlimactic with Clark beating Hale with better than 60% of the ballots cast.

Two years later, Congressman Clark faced the man who quite nearly won the GOP primary two years earlier: Henry Dworshak, who would enjoy an even longer political career. Still, 1936 was a banner year for Democrats nationally and in Idaho, the only exception was the ever-popular William E. Borah. Once again, Clark won with better than 60% of the vote.

As many congressmen do, D. Worth Clark was casting his eyes toward the United States Senate. Of course, there was no beating Borah, and the other seat was occupied by James P. Pope, a former mayor of Boise and a Democrat who had first been elected in 1932 on Franklin Roosevelt’s coattails. Pope was a stalwart of the New Deal in the Senate and a loyal supporter of Roosevelt’s program. True to his word, D. Worth Clark had a wide independent streak and did not hesitate to vote against the New Deal when he thought it was contrary to the feeling in Idaho. Harold Yeamans, a blind attorney from Buhl who had twice run for Congress inside the Democratic primary, summed up the feeling of many staunch New Dealers in the Gem State. “President Roosevelt should put a candidate in the field against every senator and representative who opposed him on vital issues – – – and that includes D. Worth Clark,” Yeamans snapped.

By October of 1937, the Idaho Statesman was reporting Congressman D. Worth Clark was a “virtual certainty” to challenge Senator Jim Pope inside the Democratic primary the following year.

As a member of the House of Representatives, D. Worth Clark did not have to take a stand on President Roosevelt’s effort to pack the U.S. Supreme Court, but the congressman announced he was unalterably opposed to the very notion. “It may serve liberalism today,” Congressman Clark said, “and a despotic reactionary tomorrow.”

Quite likely, Clark wanted to separate himself from Senator Pope, who supported the president. Clark’s stand won him plaudits from the Statesman, which commented, “He exhibits a high quality of courage which must be applauded by everyone.” Noting the congressman had been largely supportive of Roosevelt and the New Deal, as well as having been critical of many decisions rendered by the Supreme Court, the newspaper admired Clark’s determination to keep the judiciary independent from the executive branch of the government.

It surprised no one in Idaho when Congressman D. Worth Clark made his challenge to Senator Pope official on March 23, 1938. Known as a tireless campaigner, D. Worth Clark knew how to reach as many people personally as possible, which is vital in a state with a small population. One example was that of Mrs. E. J. Cummings, a columnist for the most widely read newspaper in the state, the Idaho Statesman. No pontificator upon politics, Mrs. Cummings was advertised as “Mrs. Idaho-on-the-Farm Writes of Cabbages and Kings, Crop Control and Other Things.” Mrs. Cummings wrote in her column about hearing from Congressman Clark. “D. Worth Clark called. Gee! Did I feel important!” Apparently, the two discussed several issues that occurred to Mrs. Cummings who noted the congressman “did not commit himself on anything … “ Still, the proud housewife and columnist wrote: “ … Compton I. White and Pope have never let me know they knew I existed.”

Clark campaigned for the Democratic nomination for the U.S. Senate by stressing his independence. That was a good strategy in a state where the most popular and revered politician in the state – – – William E. Borah – – – was so independent that President Calvin Coolidge once wondered how Borah, who enjoyed horseback riding, could bring himself to travel in the same direction as the horse.

David Worth Clark won the Democratic primary, ending the political career of Senator James P. Pope and causing President Roosevelt to declare his victory as “immoral.” FDR huffed that Clark had narrowly defeated Senator Pope because as many as 20,000 Republicans had crossed over to vote for him. Clark won the general election decisively, dispatching Republican nominee Donald Callahan.

Once in the Senate, Clark joined the powerful “isolationist” bloc of which William E. Borah was one of the leaders. D. Worth Clark arrived in the United States Senate at a critical juncture when foreign policy was eclipsing the New Deal domestic policy. Fear of American involvement in another foreign war knew no political party; the non-interventionists were both Democrats and Republicans. Nor did the non-interventionists find themselves bound to either conservatism or liberalism; rather they agreed on American foreign policy and fought hard against any effort by Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull to tinker with, weakening or otherwise diluting neutrality legislation.

Pearl Harbor changed the minds of virtually every American and formerly isolationist senators faced primary challenges and frequently lost. Times and attitudes change. D. Worth Clark encountered a primary challenge from Glen Taylor, a showman who had made himself a toupee and sang with his family. In a four-man primary, Taylor, who ran to the left of Senator Clark, eked out a win by 216 votes. Once out of the Senate, Clark began a law practice in Washington, D.C., and Boise.

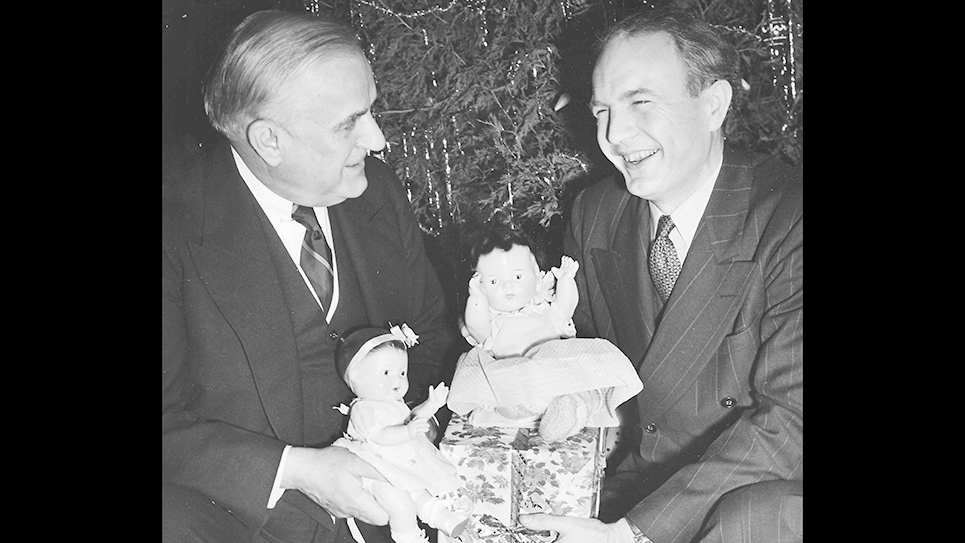

In 1948, the former senator traveled to China as an investigator for the Senate Appropriations Committee, headed by Tennessean Kenneth McKellar. The United States had continually poured billions of dollars into China to prop up the government of Chiang Kai-Shek, which appeared to be ready to topple from the civil war with the Communists, led by Mao Zedong. Even TIME magazine, which had been such a harsh critic of Clark while he served in the U.S. Senate, stated his trip to China had consisted of a “hardworking month of travel and talk with Chinese on all levels … “

Clark returned to Washington, D.C., and proposed “immediate and extensive” additional military aid, as well as “combat advisory aid,” money for military operations, and further monetary aid to “stabilize” the Chinese currency, which was in a deplorable condition. D. Worth Clark also recommended “strict U.S. supervision of the distribution” of monies spent and supplies provided to China. Much of the money that had been sent to China during World War II had never been spent for what it had been intended but rather had been eaten up by graft and corruption. The former senator from Idaho concluded his report to his one-time colleagues with a blunt statement. “Piecemeal aid will no longer save failing China from Communism. It is now an all-out program or none, a fish-or-cut-bait proposition.”

Two years later, D. Worth Clark sought a political comeback by challenging the man who had beaten him in the 1944 Democratic primary: Senator Glen Taylor. A wide swath of the electorate in Idaho was embarrassed by Taylor’s behavior in the Senate and many Democrats were still angry over Taylor having accepted the vice-presidential nomination of former vice president Henry A. Wallace’s “progressive” party in 1948. The Wallace campaign was accused of having been seriously infiltrated by Communists, which later proved to be true. Taylor never really recovered from his apostasy. Worth Clark beat Glen Taylor by 948 votes with Congressman Compton I. White running a respectable third. The former senator lost the general election to GOP nominee Herman Welker, who went on to become one of the closest associates of Wisconsin Senator Joe McCarthy in the Senate.

In 1954, D. Worth Clark moved his family to Los Angeles where he practiced law. The former senator had invested in radio stations in San Francisco, Van Nuys, California, and Honolulu, Hawaii. Clark also held an interest in a bank in Las Vegas. On the evening of June 19, 1955, Clark was watching television with his wife Virgil and his daughter when he was stricken with a heart attack and died. D. Worth Clark was only 53 years old.

© 2024 Ray Hill