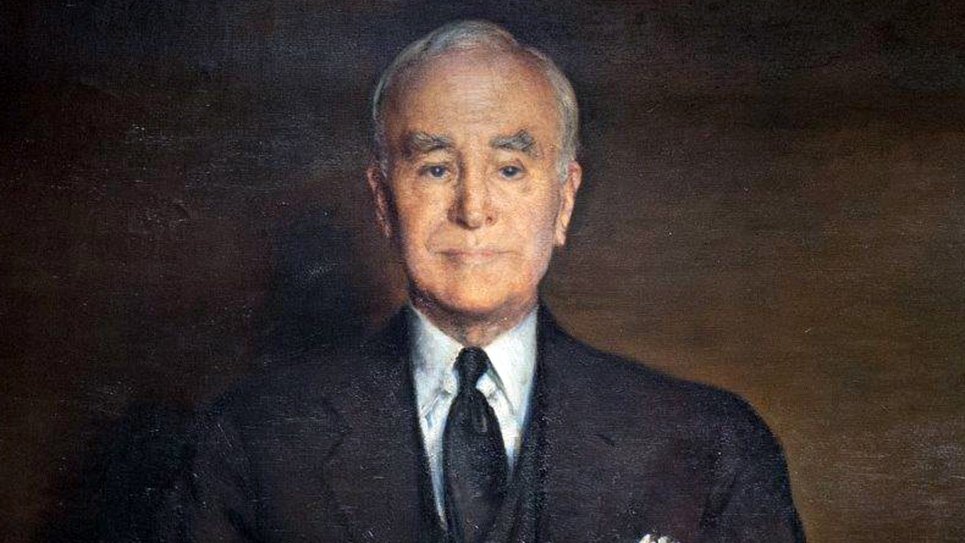

The Last of the Gray Wolves: James Bowler

By Ray Hill

I would be shocked if a single reader of this column, which draws some of the best-informed people on political history in many instances, has heard of James B. Bowler before. Yet he is notable for a few reasons, one of which is being one of the oldest freshmen to take his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. James Bowler was 78 years old when he first took the oath of office to succeed Adolph Sabath as the congressman from Illinois’ Seventh Congressional District. Bowler had been a prominent figure in Chicago’s oftentimes vicious politics for more than half a century, serving on the Chicago Board of Aldermen for 42 years. James Bowler was the last of the pack of “Gray Wolves,” which had run Chicago once upon a time. Bowler became known as the “Silver Fox” of Chicago politics.

The most powerful members of the Chicago city machine were a colorful lot known by journalists of the day as the “Gray Wolves,” due to their age, experience and years of service. Most of them had colorful nicknames to go along with their political profiles. John Powers was known to both reporters and his constituents as “Johnny De Pow,” while John Coughlin was known as “Bathhouse John Coughlin,” and Michael Kenna was known as “Hinky Dink Kenna.”

For over 45 years, Adolph Sabath had been the congressman from the heart of Chicago. The title of “Dean of the House” is reserved for its longest-serving member and Sabath won that designation on April 1, 1934, and held it for 18 years until he died on November 6, 1952. Chicago was ruled by a potent political machine and the machine rewarded those who had served it loyally by kicking some members upstairs and sending them to Congress. The machine considered the real power to be centered in city hall but occasionally the organization needed something from Washington, D.C.

James Bowler had been one of the more successful politicians and had been around for so long that he predated the ruling machine. Chicago’s political organization had enjoyed several permutations and iterations. Bowler had been elected a Chicago City Alderman in 1906, the same year Adolph Sabath won a seat in the House of Representatives. For a member of Chicago’s oftentimes distinctly odious political machine, Bowler had a very unusual background, having been a professional bicycle “endurance rider and racer.” Yet Bowler was also known as a fellow with a lot of friends and, even more importantly, no political enemies. Bowler’s rise in politics began when he was selected by John Powers to become the 19th Ward’s second Alderman. Bowler remained personally loyal to his benefactor and apparently had some integrity as he was the author of the ordinance which increased the number of wards from thirty to fifty, but also each ward was to be represented by only one Alderman. Bowler voluntarily gave up his seat so that John Powers could remain in office. Bowler was named to the newly created job of Chicago Commissioner of Compensation. When Johnny De Pow died, James Bowler was elected to replace him. Bowler resigned his seat on the board of aldermen in 1934 in order to become Commissioner of Motor Vehicles in the administration of Mayor Edward J. Kelly. Bowler decided he preferred being a member of the board of aldermen and was reelected in 1935.

Bowler also became affluent, owning a successful insurance business. The alderman was also very interested in horse racing and when his colleague Bathhouse John Coughlin died, Bowler bought Coughlin’s insurance agency and his stable of racehorses. When Mayor Anton Cermak was hit and mortally wounded by a bullet intended for President-elect Franklin Roosevelt in Miami in 1933, he had just left Jim Bowler at the horse races in Bayfront Park.

Chicago’s bloody history is usually associated with Al Capone, prohibition and organized crime, but it was also a byproduct of politics. Chicago endured what became known as the “Aldermen’s Wars,” which had been ignited by hard-fought political contests for seats on Chicago’s Board of Alderman. Most specifically, it began when Anthony D’Andrea ran against James Bowler for alderman in 1916. The campaign and election were markedly noted for its violence, which sparked the Aldermen’s Wars. It lasted for five years.

When Bowler died, TIME magazine recalled the alderman had recruited his “own rifle-equipped ‘army’ to hold out against gangster attempts to invade and take over his ward.” TIME also noted Bowler had “shared power all through the boodle days with ‘Hinky Dink’ Kenna and his close friend ‘Bathhouse John’ Coughlin … “

The Aldermen’s Wars saw 30 people killed over the five bloody years it lasted. Anthony D’Andrea was an unsavory character, to say the least, a former priest who had been excommunicated, which had to shock the thousands of good Catholics inside the district, and a convicted counterfeiter. The Chicago Tribune reported Antonio D’Andrea had been “a power in the old ‘red light’ district,” which of course was the area where prostitution thrived and was an operation of organized crime. D’Andrea had ties to organized crime and newspapers of the time believed D’Andrea’s candidacy was an attempt by local crime lords to take over James Bowler’s ward. Anthony D’Andrea, despite his background, was popular with his fellow Italian-Americans, as well as organized labor.

Frank Lombardi, an associate and supporter of Alderman John Powers, was shot and killed in a Chicago saloon by Samuzzo Amatuna, who was only 17 years old at the time. Both the machine adherents of Johnny De Pow and Jim Bowler armed themselves along with the supporters of Anthony D’Andrea.

Perhaps the most ominous and lurid feature of the Alderman’s Wars was a tree located at 725 S Loomis Street. This particular tree had a name carved on it. Later, that person was found murdered. Another name was carved into the tree and another. It wasn’t long before Chicago’s enterprising reporters and locals began referring to the tree as “Dead Man’s Tree.” The machine was able to repulse the repeated and determined efforts of Anthony D’Andrea to win a seat on the board of alderman and take over control of the ward run by Johnny De Pow and Jim Bowler. Three times D’Andrea ran for alderman; 1916, 1919 and 1921. The warfare included twice bombing the home of Alderman John Powers. Another bombing, likely in retaliation, took place at a political rally for Anthony D’Andrea, with half a dozen supporters being injured. There were also additional bombings, which included another private home of a D’Andrea supporter and the campaign headquarters for D’Andrea as well.

Paul Labriola, a bailiff in Chicago’s Municipal Court and patronage employee of Alderman John Powers, had been pressured to join many of his fellow Italian-Americans in supporting Anthony D’Andrea. Labriola refused, which earned him the enmity of several D’Andrea backers. Labriola was gunned down and murdered; Labriola’s murder was quite reminiscent of that of Harry Raymond (Raimondi), another Powers supporter, which occurred on the same day. Almost immediately Powers offered a $5,000 reward for information on the triggermen. The powerful alderman was highly conspicuous at Paul Labriola’s elaborate funeral. When the elderly alderman gazed into the open casket and viewed Labriola’s body, he burst into tears. “I can’t help it, friends,” Powers explained, wailing, “He died for me.”

D’Andrea lost each of his election bids and following his loss in the 1921 campaign, he announced he was done with politics. Described by the Chicago Dispatch as the “political dictator” of his ward, Anthony D’Andrea’s announcement that he was through with politics availed him little in the end. As D’Andrea was leaving his home, a passing car fired at the boss, fatally wounding him. The weapon which killed D’Andrea was a shotgun and near the gun, which had been discarded, was a battered hat. Inside the headband of the hat was a folded $20 bill and a note, which said “for flowers.”

In death, D’Andrea was denied the rites of his church, although two of his brothers were priests. The family had intended to bury Anthony D’Andrea in Mount Olivet Cemetery, but the archbishop of Chicago forbade it. The only explanation was a terse statement from an underling that D’Andrea had not lived as a Catholic and would not be buried as one. As he lay dying, Anthony D’Andrea sought to rejoin the Catholic Church and “was given the sacraments of penance, holy communion and extreme unction … ” D’Andrea’s funeral was held on the street near his home. It was reputed to be “the largest and most expensive funeral ever given any Italian” in the City of Chicago until that time.

The Aldermen’s Wars was not quite over with the death of Anthony D’Andrea. Two supporters of D’Andrea vowing vengeance for their leader’s murder were killed shortly after saying they would get revenge. That ended the Aldermen’s Wars. Had not Powers and Bowler used the same tactics employed by those seeking to take over their ward, they would have been routed.

Adolph Sabath’s death came as no surprise to anyone as he had been suffering from pancreatic cancer for some time. When Sabath died, Jim Bowler told friends he would like to cap off his political career by serving in the House of Representatives. Being a loyal member of Chicago’s city machine, Bowler had always supported Sabath and had never tried to challenge him to go to Congress. When Sabath had a dispute with Alderman Joseph Ropa, an effort was made to eliminate Sabath’s seat in redistricting. It was Jim Bowler who had saved Sabath’s seat in the House.

Any thought of opposition to Bowler’s candidacy for Congress was swept away when the eight ward leaders comprising the congressional district all endorsed the alderman to succeed Adolph Sabath. Although he was virtually assured of winning the special election called for July, Bowler said he did not intend to resign his seat on Chicago’s Board of Aldermen “until I get the certificate of election July 7.” Bowler held the important post of chairman of the Rules Committee, which then engaged in mapping out the redistricting of the aldermanic wards.

Just about every municipality and locality has its own self-appointed and self-designated “good government” group and Chicago was no different. A committee of citizens had proposed Miss Jessie Binford, a 76-year-old who had just retired after 36 years as the executive director of the Juvenile Protective Association. The committee wanted Miss Binford’s candidacy to be considered by the Democratic ward committeemen who had already endorsed Jim Bowler. William Jones, a member of the committee of citizens who believed she should be elected, said Miss Binford would “bring prestige locally and nationally” to the Seventh Congressional District of Illinois. No one who knew anything about politics could have been surprised when the committee ignored the demand.

During his four years in the House of Representatives, James Bowler quietly tended to his duties and pushed for projects and improvements and federal dollars for Chicago.

Congressman James Bowler was seriously ailing by his 1956 reelection to the House of Representatives. Bowler easily dispatched his Republican opponent by a 3-1 majority but his health continued to fail following a heart attack. Also suffering from nephritis and severe arthritis, Bowler remained confined to his comfortable six-bedroom home on California Street. When Congress convened for its new session on January 3, 1957, Congressman Bowler remained in Chicago. The congressman was too ill to go to Washington and never came back to the House of Representatives.

James Bowler died on July 18, 1957, and his passing was immediately lamented by Mayor Richard J. Daley, who had consolidated the power of the Chicago machine into his own hands. Bowler, while never influential in the House of Representatives, was at least a distinguished successor to Adolph Sabath. The machine was not as selective in the special election to choose a successor to Congressman Bowler. The Daley machine settled on a criminal defense attorney who served in the Illinois State Senate and had been associated with Al Capone during his heyday.

© 2024 Ray Hill