The Minority Leader: Charles L. McNary of Oregon

By Ray Hill

It may surprise readers there was a time when Oregon was a highly Republican state. In fact, it was the home state of Charles Linza McNary, who served as minority leader during some of the most difficult years for Republicans. McNary was the GOP leader in the United States Senate at the apex of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal Administration. Following the 1936 election, there were only 15 Republican senators out of 96 (Hawaii and Alaska were not yet states). Yet Charles McNary remained a highly effective leader and shrewd strategist who was able to maximize the sometimes-scanty minority’s influence. When dark horse candidate Wendell Willkie captured the GOP presidential nomination in 1940, a member of the Republican Old Guard was needed to balance the ticket. Willkie asked McNary to become his running mate and the 66-year-old senator agreed.

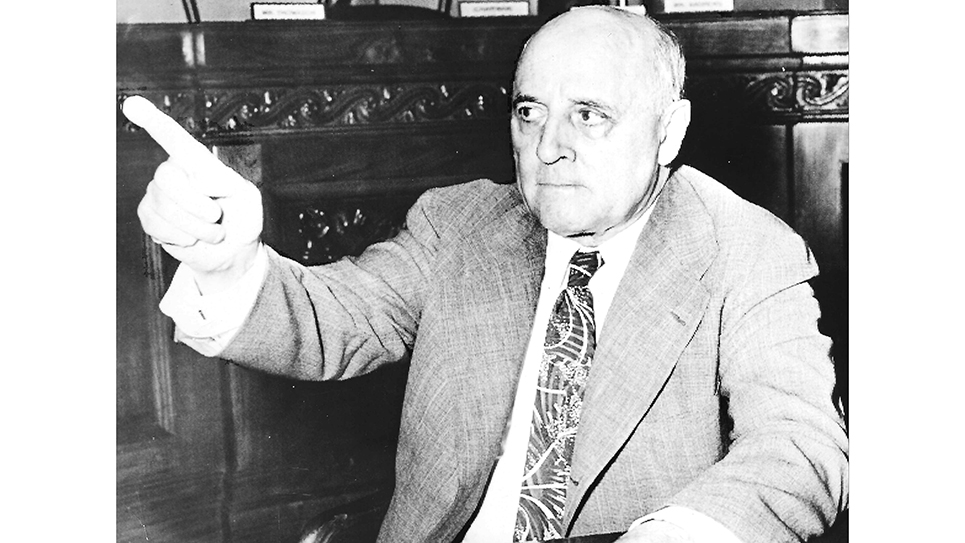

A crafty opponent as well as a legislative expert who knew how to get things done, McNary was well-liked amongst his colleagues. TIME, the most widely read news magazine of its day, acknowledged Charles McNary had long puzzled New Dealers who called the Oregon senator “able, shrewd, liberal, weary, lazy, cynical.” McNary was a tall, sandy-haired dapper man, well attired and usually sporting a jaunty bowtie. One of the quirks of McNary was getting to his feet from his desk on the front row of the Senate Chamber and “shooting his cuffs” which were always white and stiffly starched. Oftentimes observers could gauge the minority leader’s mood by how he tugged at his cuffs, whether he would good naturedly pick at Democrats or whether he was angry and ready to send a pointed barb at the opposition. TIME noted McNary had won many a skirmish “with nothing up his sleeve but pure, political cunning.”

McNary was well-liked not only by his colleagues but also by much of the Capitol Hill press corps. The senator from Oregon knew what was going on in Washington, D.C., and was apparently one of the best off-the-record sources for favored newsmen.

When he died, Salem’s Statesman Journal newspaper noted Charles McNary’s life was “the Modern History of National Legislation.” McNary is largely remembered today for his sponsorship of the McNary-Haugen Act, which was written to help farmers and bitterly opposed by many inside his own party, although both McNary and House sponsor Gilbert Haugen were Republicans. “Charlie Mac” became highly popular with farmers and was considered an authority on farm aid, which was a subject near and dear to his heart. McNary once warned the members of his party to “quit its abstractions and alarms and get down to the level of human sympathy and understanding.” McNary followed his own advice during the First One Hundred Days of the New Deal, voting for practically all the legislation recommended by President Roosevelt. Instrumental in the development and passage of the massive Bonneville Dam and power project, McNary supported TVA, Social Security and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration Act.

Charlie McNary’s story was uniquely American in his rise to security and prominence. The tenth child of his parents, McNary was four when his mother died and nine when his father died five years later. The McNary orphans banded together out of necessity and love to eke out a living. Charlie McNary became a paperboy while also working on farms and orchards to help provide for his family. John Hugh McNary was elected county recorder in 1890 and hired his younger brother. Charlie McNary eventually moved to California to attend Stanford University, against the advice of his grandfather who urged the boy to go into the grocery business. Instead, McNary took the $28 he had saved over a summer from working and went off to college. To support himself, the future senator worked as a waiter. McNary went home to Oregon after his family asked him to return with the understanding that he would study to become a lawyer. Charlie McNary did not give up his pursuit of the law and read the law under his brother John and attorney Sam Hayden. McNary passed the Bar exam in 1898 and engaged in the practice of his profession. Charlie joined John Hugh McNary in starting the law firm of McNary and McNary. John McNary also worked as a deputy assistant district attorney. As a lawyer, McNary became well acquainted with agricultural issues. It seems second jobs were second nature to the McNary family as Charlie began teaching property law at the Willamette University College of Law. In 1908, Charles McNary became Dean of Willamette’s Law School. McNary also bought the old family farm and for the rest of his life, it remained a working enterprise.

Charlie McNary married his college sweetheart, Jessie Breyman, and the couple enjoyed what was by all accounts a happy marriage. Jessie was killed in an automobile accident while returning home from her mother’s funeral when the car flipped and crushed her to death. It was a terrible blow to Charles McNary.

McNary continued his rise to prominence by becoming counsel to Oregon’s state railroad commission and was appointed to serve on the state Supreme Court as a justice. McNary enjoyed friends in both the conservative and progressive wings of Oregon’s Republican Party, although he was a thorough-going progressive in his outlook. McNary was an outspoken supporter of the direct election of United States senators, public power, and labor through advocating for the eight-hour workday. McNary always enjoyed the support of organized labor during his political career.

McNary suffered the only defeat of his long political career when he lost the Republican nomination for the Supreme Court by a single vote. The conservative and progressive factions of Oregon’s Republican Party were feuding, and McNary proved to be one of the few agreeable to both groups. Charlie McNary became chairman of Oregon’s Republican Party and promptly worked to ensure the election of Charles Evans Hughes who was campaigning to unseat President Woodrow Wilson. In a very close election, Evans lost the White House but carried Oregon. In 1917, United States Senator Harry Lane died suddenly. It quickly became clear McNary was one of a handful of contenders to be appointed to the senatorial vacancy by Governor James Withycombe. Six days after Senator Lane’s death, the governor appointed Charles L. McNary to the United States Senate.

Almost immediately McNary demonstrated he was an adept campaigner by defeating Robert Stanfield, the speaker of Oregon’s House of Representatives, handily in the GOP primary. McNary faced yet another formidable challenger in the general election in Oswald West, a former governor. McNary won the general election decisively only to leave office as he had not run to finish out Senator Lane’s term. Frederick Mulkey won that special election and served a few months before resigning so that McNary could gain a seniority advantage over incoming senators. McNary took his seat in the United States Senate in December of 1918 where he remained until his death.

Only once did McNary face a daunting reelection campaign for the Senate. At the peak of Franklin Roosevelt’s popularity in 1936, the senator faced the voters of Oregon once again. McNary faced Willis Mahoney, the mayor of Klamath Falls, who ran as an all-out backer of Roosevelt and the New Deal. Mahoney delighted in asking audiences when they had last seen McNary. It was a very close election, which McNary won by just over 5,000 votes. Still, McNary’s personal popularity saved him from the same fate as many of his colleagues where Republicans were an endangered species.

The elections of 1932 had begun the decimation of Republicans in both the House and the Senate. Majority Leader James E. Watson of Indiana had been defeated in the Roosevelt landslide and McNary had become the minority leader, a position he held until he died in 1944. It was following the 1936 elections that Charles McNary demonstrated his political sagacity when President Roosevelt sought to pack the U.S. Supreme Court. McNary advised a strategy of allowing Democrats to tear each other apart while Republicans largely watched from the sidelines. McNary’s wise counsel focused the opposition to the president’s proposal inside his own Democratic Party to take center stage, robbing the Roosevelt Administration of the powerful argument that it was a partisan issue. The idea of packing the Supreme Court was opposed by every Republican in the Senate, but GOP senators reluctantly followed McNary’s leadership and watched in wonder as a full-blown mutiny occurred in Democrat ranks. Burton K. Wheeler, a progressive Democrat from Montana, became the leader of the court-packing opponents in the Senate. The coalition of Republicans and conservative Democrats would become more powerful following the 1938 midterm elections and crippled the dominance of Roosevelt politically. No longer could FDR expect a compliant Congress merely to rubberstamp whatever he laid before it. That largely was the doing of Charles McNary’s shrewd leadership.

McNary remarried in 1923 to Cornelia Morton and the couple adopted a daughter, Charlotte, whom the senator positively doted upon. Each summer, McNary looked forward to leaving hot and humid Washington, D.C., for the splendor of his farm in Oregon where the weather was usually wonderful. The senator spent time in his magnificent garden at his modest but quite comfortable farm cottage. The cottage was surrounded by magnificent fir trees, which were reflected in ponds created by a natural spring. McNary’s farmhouse was known as “Fircone.” Located six miles from Salem, Fircone was heaven on earth for Charlie McNary.

The election of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the arrival of the New Deal eliminated many Old Guard Republicans who were thorough-going conservatives, as well as President Herbert Hoover, who believed Charlie McNary was too liberal. Many of the Republicans who survived the ascendancy of FDR and the New Deal were Republican progressives like Hiram Johnson of California, William Borah of Idaho, Gerald P. Nye of North Dakota and McNary.

Charles McNary was a man with a magnetic personality, recognized for his ability as a member of the United States Senate. One of the essential qualities of McNary as a person was his understanding of the human condition. Charlie McNary had the ability to make lasting friendships, a key ingredient in success in any legislative chamber.

When nominated for vice president, McNary had never seen nor met Wendell Willkie. McNary opened his vice-presidential campaign in Oregon before an audience of some 12,000 people. Senator McNary paid tribute to the sturdy pioneers who had traveled what became known as the “Oregon Trail.” “Land, if you had to work it, was never free,” McNary told his listeners. “Men paid for it in sweat, blood and loneliness, if not in dollars.” Oregon had prospered McNary said precisely because “Americans had not then been instructed that they must look to Washington for inspiration and sanction for their every act. . .”

The Willkie-McNary ticket lost the 1940 election to Roosevelt, but it had run far better than its predecessors. Charles McNary ran for yet another six-year term in 1942 and won easily. Shortly after his reelection, McNary began experiencing odd symptoms and experts at Bethesda Naval Hospital discovered the senator was suffering from a brain tumor. The senator underwent an operation to remove the tumor. Following his surgery, McNary went to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to rest and recuperate. One worried sister went to Florida where she spent two weeks with her ailing brother. Reports indicated McNary was making rapid progress in his recovery, taking short walks around the area. Because the news from the senator’s Florida sojourn was so positive, his death on February 26, 1944, came as a distinct shock to his family, friends, Oregon and official Washington, D.C.

Tributes poured in from across the political spectrum. Vice President Henry Wallace, the mystical progressive, remembered McNary as “one of the finest men I ever knew.” Republican U.S. Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan thought Charles McNary was “one of the wisest, soundest and ablest statesmen in the public life of this generation.”

© 2024 Ray Hill