Robert L. Owen of Oklahoma

By Ray Hill

Having been born in Oklahoma while my father was in the military, I have always had a special interest in the politics of the Sooner State. This is being written as the anniversary of Oklahoma being admitted into the union of the United States, November 16, 1907, is celebrated. Robert Latham Owen Jr. was one of Oklahoma’s first two United States senators. Owen became a workhorse in the U.S. Senate where he was instrumental in writing and passing the Federal Reserve Act and the Farm Loan bills. Part Native American, Robert L. Owen earned a well-deserved reputation as a friend of the Cherokee people. A potent orator, Owen possessed a voice rich and liquid, but could also grate like a file when the senator was harsh in his criticisms. Owen was unusual as a politician. Never one to pat people on the back or shake as many hands as possible, Robert L. Owen did not pander to special interest groups and never forgot his personal dignity.

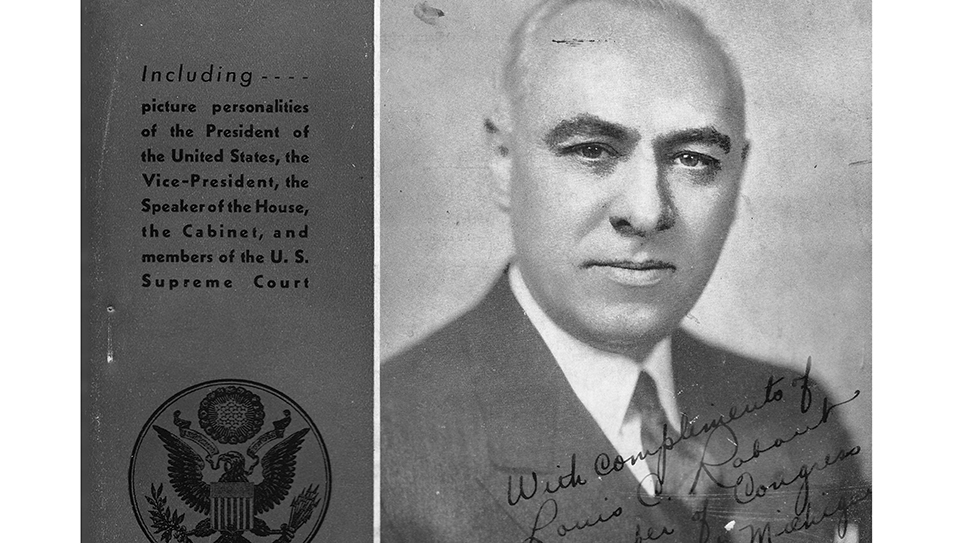

A man of striking appearance and intense black eyes, Robert L. Owen was once described as looking like a matinee idol. Owen had been born in Lynchburg, Virginia, to a prosperous family; Owen’s father was the president of the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad. Robert Owen experienced a profound reversal of fortune when his family lost everything during a national financial panic in 1873 and his father died while he was still a teenager.

Throughout his life, Owen enjoyed success in each of his fields of endeavor. Following his father’s passing, Robert L. Owen set out for the Indian Territory (Oklahoma) where he worked hard to make a life for himself. As was often the case during those times, Owen was a schoolteacher, although the future senator taught Cherokee orphans. Owen tried his hand at journalism, an Indian agent for the federal government, earned a law degree, and became a banker, starting a bank in Muskogee in 1909 which weathered some very difficult times and unlike many other financial institutions, never failed.

As an attorney, Robert L. Owen became renowned for his legal abilities. The future senator represented the Cherokee Nation in litigation involving land issues. The Eastern Cherokees had notoriously been moved to the “Indian Territory,” as Oklahoma was then known, trudging the “Trail of Tears.” Owen represented the Eastern Cherokee in their lawsuit against the government of the United States in 1900. Owen demanded payment owed to the Cherokee under a treaty with the United States signed in 1835. Robert Owen sued saying the Cherokee were owed significant compensation for the lands lost during the removal of the Indians. The courts agreed with Owen and awarded the Cherokee Nation almost $5 million (more than $157 million today). Owen’s success in the courtroom caused other Indian nations to hire him, including the Choctaw, Chickasaw and Western Cherokee.

Active in Democratic politics, Owen advocated for statehood for Oklahoma. Owen was a progressive for the times, backing giving women the right to vote and the right of the people to vote for their United States senators by direct election. When Oklahoma held a primary to select the nominees of the Democratic Party for the U.S. Senate, Owen was a candidate. At the time, senators were still elected by state legislatures, although the Oklahoma legislature honored the wishes of the voters who had supported Robert L. Owen. Owen’s new colleague from Oklahoma, Thomas P. Gore, was blind and the two men drew lots to determine the length of their respective terms as they had been elected simultaneously. Owen’s term was to last five years and he faced the voters in 1912 for a full six-year term of office.

Senator Owen was challenged in the Democratic primary by Governor Charles Haskell. Reputedly, Owen maintained a mailing list of some 300,000 Oklahomans in a state whose population in 1912 was 1.7 million people. Owen turned back Haskell’s bid and won the general election. Senator Owen was reelected in 1918.

It was Robert L. Owen who had pressed the United States Senate to create a committee on banking; eventually, Owen was successful, and the Senate Banking & Currency Committee was the result of his efforts. Senator Owen became the new committee’s first chairman, a post he held until 1919. It was because of his chairmanship of the Senate Banking Committee that Owen became one of the sponsors of the Glass-Owen Act, which created the Federal Reserve system. Rejecting the idea of central banks, Owen worked with Congressman Carter Glass of Virginia. There were differing and competing proposals for a Federal Reserve system being considered by Congress. The approach taken by Congressman Glass centered around his proposal to create a Federal Reserve dominated by the private sector; the Board of the Federal Reserve System, under the Glass proposal, would be largely comprised of private bankers. Another proposal was made by Republican U.S. Senator Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island, the grandfather of Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller. Senator Aldrich proposed a decentralized model thoroughly dominated by private interests. Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo, who was to marry one of President Wilson’s daughters, urged the creation of a central bank inside the Treasury Department. Robert Owen, working with the assistance of former Assistant Secretary of the Treasury and Congressman A. Piatt Andrew, pushed a course that navigated the middle of the road between the various proposals being considered. Owen’s bill created eight regional banks, a currency board whose members were to be appointed by the federal government, and most of those elements remained in the bill President Wilson pressed the Senate to accept.

In the end, the Senate Banking Committee was almost evenly divided between the Owen Bill and a rival bill sponsored by the Democratic Leader of the Senate, Nebraska’s Gilbert Hitchcock. In the first vote by the full Senate, Owen’s bill failed on a vote of 43-41. A second vote saw Senator Owen’s legislation pass the Senate 54-34. In its final version, the Federal Reserve Bill more closely resembled the original legislation proposed by Robert L. Owen than that of Congressman Carter Glass. Appropriately, there is a Robert Latham Owen Park behind the Federal Reserve Building in Washington, D.C.

Republicans had won the 1918 midterm elections, which endangered Wilson’s dream of American participation in the League of Nations and ended Owen’s chairmanship of the Senate Banking Committee. The president boarded a special train and toured the American West in a campaign to urge the people to back the Treaty of Versailles. Wilson suffered a stroke which left him paralyzed on his left side. The train rushed back to Washington, D.C., where he was confined to his bed for weeks. First Lady Edith Wilson and the president’s physician, Admiral Cary Grayson, issued cheerful reports about Wilson’s progress and in the absence of television, few Americans realized just how feeble the president truly was. Almost entirely hidden from the view of the public, Edith Wilson kept strict vigil over her husband and decided who saw Wilson and what matters were to be seen by the president. Yet Wilson wanted to be nominated for a third term. Wilson never recovered from his stroke and while his mind seemed to be clear, it had accentuated the president’s more unpleasant personal traits. Querulous, inflexible and sometimes just plain irrational, the president remained physically quite feeble.

Even Edith Wilson and especially Cary Grayson realized Wilson was utterly unable to campaign. So too did the president’s closest political associates know that giving Woodrow Wilson a third presidential nomination would bring disaster to the Democratic Party. Virtually all officials in Washington understood Wilson was not well enough to run again. Senator Robert L. Owen became a candidate for the Democratic nomination for the presidency. Owen’s presidential campaign never caught fire and he amounted to little more than a favorite son candidate at the 1920 Democratic convention.

That same year Senator Owen broke politically with his colleague from the Sooner State, Thomas P. Gore. Unlike Owen, who had supported President Wilson and the war effort, Gore had been critical of Wilson’s foreign policy and the First World War. Nor was Gore supportive of Wilson’s vision of the peace to come after the war. Senator Owen did not endorse his colleague’s reelection bid and Congressman Scott Ferris beat Gore in the Democratic primary. Oklahoma Democrats were stunned when Republican Congressman John W. Harrell won the general election.

Senator Owen changed his own opinion of the cause of the First World War and came to believe the heavy financial penalties and war reparations, which eventually led to the rise of Adolf Hitler, was a terrible mistake on the part of the Allied powers. Owen’s beliefs were not popular with many inside his own political party. Some Democrats were made uneasy by Owen’s opinion, fearful it would erode the legacy of Woodrow Wilson.

The 1920 election saw women vote for the first time for presidential candidates and it soon became clear the American people were weary of the Wilson Administration. Republicans won a sweeping victory, electing Warren G. Harding to the presidency in a landslide and giving heavy majorities to the GOP in both houses of Congress. With a Republican administration and Congress, Robert L. Owen saw his own influence diminish accordingly. Senator Owen announced he would not run again in 1924 and retired at the expiration of his term the following year.

The 69-year-old former senator did not go home to Oklahoma but rather remained in Washington, D.C. where he began a lucrative career as a lawyer and lobbyist. Owen and his wife also adopted their grandson, who took the name of Robert L. Owen III.

Safely out of public office and enjoying his profitable new career, former Senator Robert L. Owen roiled his own Democratic Party with his blunt refusal to support the presidential nominee in 1928. Governor Alfred E. Smith of New York was wringing “wet,” one of the most notable foes of national prohibition in the country, as well as a proud product of the notorious Tammany Hall political machine. Much of the opposition to Smith’s candidacy was due to his religion, as he was the first Catholic to be nominated by a major political party for the presidency. Oklahoma was an overwhelmingly Protestant state.

“If ever there was a man fitted to be an advance agent of prosperity, it is Herbert Hoover,” Owen thundered. It became a bitterly ironic statement. Owen became the first Democrat of note to defect to Hoover and refuse to support Smith. Four years later, Senator Owen jumped aboard the campaign to nominate Franklin D. Roosevelt for the presidency.

Robert L. Owen was one of those former senators who never went home, but rather continued living in Washington, D.C. Owen resumed his activities as a lawyer and lobbyist in the nation’s Capitol until 1935, when he lost his eyesight. When the United States Senate debated American entry into the United Nations in 1945, both of Oklahoma’s first senators sat quietly on the floor, a privilege granted to former members. Both were blind at the time, and they listened intently to the discussion.

The elderly former senator began ailing in the last year of his long life. Owen’s wife, Daisy, had died in 1946; the couple had been married since 1889. The 91-year-old former senator underwent an operation at Washington, D.C.’s Emergency Hospital, but Robert L. Owen died on July 19, 1947.

When Senator Owen died, the Chickasha Star remembered the former lawmaker as “the greatest scholar and statesman that Oklahoma ever produced.”

Even in death, Robert Latham Owen did not go back to the Sooner State which had honored him time and again. Instead, Owen’s mortal remains went to his birthplace of Lynchburg, Virginia, where he was interred beside his mother. Ironically, the Spring Hill Cemetery is also the final resting place of Owen’s sometime rival Carter Glass.

The former senator’s grandson and namesake erected an impressive headstone over his grandfather’s grave.

© 2024 Ray Hill