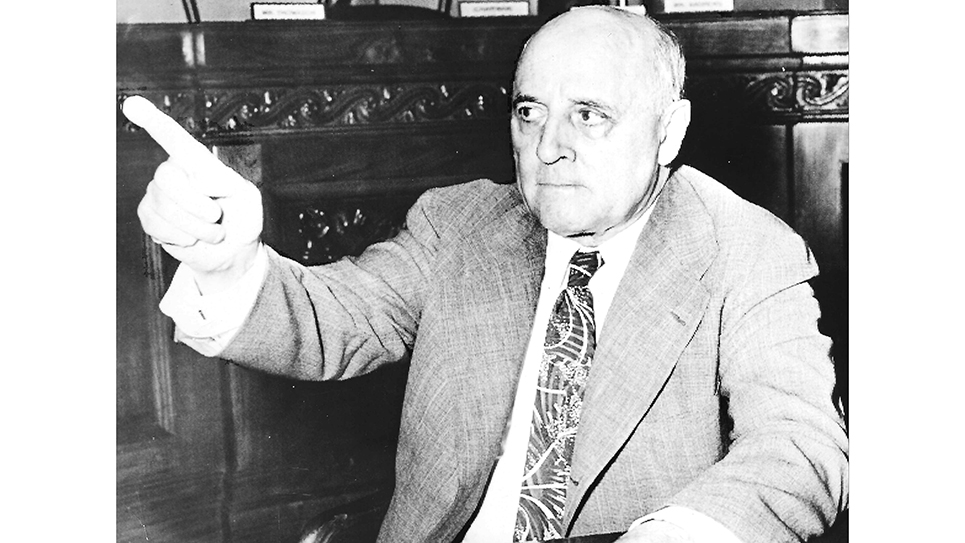

A Missionary In Politics: Walter Judd of Minnesota

Walter Judd lived a remarkable life, long in years and purpose. Judd was by profession a doctor and a good one. Judd was also a man of deep and abiding faith who worked as a medical missionary amongst the Chinese. Walter Judd was also one of the most visible anti-Communists in the United States. Judd, while in China, had only barely escaped being murdered by the Communists. “I had my belly full of them,” Judd recalled decades later with a bitter smile. While working at the Chinese-Mongolian border, Judd was captured by the invading Japanese Army and held as a prisoner of war for five months. Eventually, he returned home to the United States where, with a missionary’s zeal, he spoke out on what was happening in the Far East. “You have a choice between your silks and your sons,” Judd candidly told thousands of astonished American mothers. As a public speaker, Walter Judd was a wonder, speaking at 240 words per minute in a high-pitched voice that usually kept his audiences spellbound.

By all accounts, Walter Judd was a remarkable man. Judd had worked his way through the University of Nebraska by washing and drying dishes while earning a Phi Beta Kappa key. When Dr. Judd sailed to China he first nearly died from malaria before being captured by the Japanese and Chinese Communists. When he returned to the United States in 1938, Judd made some 14,000 speeches in two years urging a change in U. S. foreign policy. Judd urged the United States not to send war supplies to Japan. As a doctor, Judd told congressmen, “I spent my time taking American scrap out of Chinese men women and children.” Judd also once wrote he was “increasingly convinced that the Chinese Communists are Communists first and Chinese second.”

Friends and neighbors led a campaign to elect Judd to Congress in 1942, raising the necessary money for a campaign and providing a steady flow of workers. Judd beat incumbent Oscar F. Youngdahl easily and swamped Farmer-Labor and Democrat candidates in the general election by a wide margin. Judd labeled himself a “progressive conservative.”

When Walter Judd won his first term in the House of Representatives, he outlined the three things he believed a good congressman should do, listing them as work for good legislation, tending to the needs and concerns of the constituency that elected him, and lastly to get reelected. Judd told his wife, Miriam, that when the other two began to interfere with the first, it was time for him to leave Congress.

Like many Midwestern states, Minnesota had been a hotbed of isolationism, which was reflected in much of its delegation in Congress. Henrik Shipstead, Minnesota’s senior U. S. senator, resembled nothing more than an old Viking and was one of the strongest noninterventionists in the Senate. If anything, his colleague Ernest Lundeen, a Farmer-Laborite, was even more rabidly against internationalism and American intervention. Lundeen was killed in a 1941 airplane crash and replaced by Republican Joseph Ball, a newspaper reporter and internationalist.

Walter Judd also rejected isolationism and supported foreign aid, saying, “It offers the way to get the most security for the least cost.” Dr. Judd also urged Americans to welcome those refugees who escaped from totalitarian regimes. When Anastas Mikoyan, an old Bolshevik from the time of Lenin, was touring the United States, the congressman refused an invitation to dine with the Soviets. When asked why, Congressman Judd tartly replied, “For the same reason we would not attend a social function honoring Hitler, Himmler, Nero or Genghis Khan.”

While in Bulgaria along with Senator Carl Hatch of New Mexico, a Democrat, and Congressman John Davis Lodge of Connecticut, a Republican, the congressional trio realized some gestures carry quite a lot of meaning. The delegation was all too well aware of the irony that decisions at the end of the Second World War had freed many millions of people from the brutality of the Nazi regime, only to relegate them to a different form of totalitarian government as satellites of the Soviet empire. The congressmen bought a funeral wreath and as they headed toward the airport, made a detour, stopping at the cemetery where the remains of Nikola Petroff lay. Petroff had been executed eight days earlier for his opposition to the Communist government. The three laid the wreath on Petroff’s grave and honored the memory of a man who died for the desire for freedom.

When the House formed an odd coalition of Republicans, Southern Democrats and New York congressman Vito Marcantonio, who hued the Communist line in Congress, to defeat a $60 million foreign aid package to Korea in 1950 by a single vote, Walter Judd was horrified. “If, on top of the blow the Administration has just dealt to the last hope of the Chinese, we here today walk out on the Koreans, what do you think it will do to the hearts and hopes and confidence in us of the other 800 million human beings in Asia? On their decisions depends more of our own future than we realize,” Judd cried.

Congressman Judd was frequently one of the most effective debaters in Congress, especially when it came time to argue the merits of appropriation bills allocating foreign aid. Judd was oftentimes the congressman who tangled verbally on the House floor with Otto Passman, a Louisiana Democrat who was a renowned junketeer, but also one who understood where every dollar of foreign aid was spent. After traveling anywhere, congressmen could expect a lengthy report from Passman. The Louisiana lawmaker routinely attempted to pare down the expense of foreign aid, sometimes slicing away the meat and muscle down to the bone. When President Dwight Eisenhower’s 1960 budget proposed spending $3.9 billion on foreign aid, Otto Passman, wearing a white linen suit, got to his feet to bellow, “First, we cannot spend ourselves rich. Second, we cannot make ourselves secure by giving ourselves away. Third, we cannot buy friends. We were once told that foreign aid would stop Communism. Now we are told it is our duty to buy our way of life for countries all over the world. But we cannot in fact improve their living standards by as much as one percent even if we should give away everything we own.”

“The question is what is to happen in our nation’s interest. Sometimes we act as if we were not at war – – – and in the most perilous situation in which the US has ever been – – – partly because it does not look like war,” Judd replied. “Therefore we do not go all out to do the things necessary to win.”

The House, with a huge Democrat majority, agreed with Passman and lopped off more than $800 million of proposed foreign aid funding.

In 1958, following a special election in Minnesota inside a heavily Republican district, Judd became alarmed when a young Democrat came within 664 votes of winning. Judd placed the blame directly on Eisenhower’s controversial secretary of agriculture, Ezra Taft Benson. Judd, along with Nebraska congressman Arthur L. Miller, personally went to see Secretary Benson, who was surprised when the two congressmen told him he must resign for the good of the Republican Party. Should he remain in office, Benson was told, it would cost Republicans 20-25 members of their caucus to be defeated in the fall elections. Judd and Miller blamed the near loss in the Minnesota special election on Benson’s decision to lower dairy price supports, which had naturally been hugely unpopular with dairy farmers. Benson, politically tone-deaf, told the congressman he was staying in office and would “continue to pursue a course which I believe is best for our farmers.” Judd had to admire Benson’s determination to do what he thought was right.

In 1960, Vice President Richard Nixon was the presumptive GOP nominee for president. A man who paid attention to every little detail of party conventions, Nixon personally selected Walter Judd to give the keynote speech of the convention which he expected to nominate him.

Judd’s congressional district had been seriously altered by redistricting in 1962. The congressman was also becoming increasingly disgruntled with his job. Judd’s view as a congressman was much like that of a physician; he knew what treatment and course was best. Walter Judd was becoming steadily buried beneath what he clearly saw as a mountain of trivia by his constituents, who brought their requests for everything from “. . . more Public Health Service grants for the University of Minnesota to Coke machines for the Minneapolis post office.” The demands on his time were such that Judd found it impossible to properly study all the pending legislation before him. “You don’t want a man to operate on you who just skims his medical books,” Judd opined. Perhaps more importantly, Walter Judd was all too aware the political coloration of his district had changed following redistricting. Previously, the congressman had enjoyed a safe seat with his district being centered in the conservative areas of south Minneapolis. After redistricting, Judd’s district took in several heavily Democratic wards, changing the political complexion completely. “I don’t know that you can get elected in the present situation unless you are willing to work day and night for it. I am not,” Judd said bluntly.

After twenty years, Judd said he was retiring. Politics encourages skepticism and the cynical wondered if Congressman Judd wasn’t attempting to stir up support to draft him as a candidate once again. “I feel there are things I can do more usefully in the remaining years of my life,” the 63-year-old congressman said. “I’m not a devious person. If I wanted to run again, I’d run.”

That same year, 1962, Walter Judd was named as one of the five most admired and influential men in Congress. In the end, Walter Judd did run again. Minnesota’s Farmer-Labor and Democratic parties had merged to form the Democratic Farmer Labor (DFL) Party. Judd’s opponent was Donald Fraser, a 38-year-old state senator. Fraser was all for the Kennedy Administration and was critical of the “obstructionist coalition of Dixiecrats and Republicans who oppose important social programs.” “Or do they want to elect a liberal Democratic majority responsive to the needs of our decade?” Don Fraser asked voters.

Much of the conversation during the campaign involved President Kennedy’s handling of the Cuba crisis. Judd’s criticism of Kennedy was pointed, and the congressman lamented the president was “a weaker person than we realized.” Fraser, naturally, defended the president, although he was taken aback when Kennedy blockaded the island.

Institutions, political and otherwise, can be and have been toppled. Donald Fraser did not find it easy to topple the political institution that was Dr. Walter Judd. Congressman Judd handily won the old confines of his old district, but lost the areas added to his district. Fraser eked out a narrow victory, winning by just over 6,000 votes.

Not having wished to run again, Dr. Walter Judd had made a game campaign in a district that had been altered to easily elect a Democrat and quite nearly closed the gap. Judd left the House of Representatives as one of its most respected members. Judd once again was one of the featured speakers at the 1964 GOP National Convention which nominated Arizona U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater for the presidency.

In 1981, Dr. Walter Judd was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Ronald Reagan. Judd lived to see the fall of the Soviet Union, which he considered a validation of the views he held throughout his long life. Following his defeat, Judd lived in the Washington, D.C., area.

Dr. Walter Judd died of cancer at age 95 on February 13, 1994. In death, the remains of Dr. Walter Judd were laid to rest in the state of his birth, Nebraska, rather than Minnesota whose people had given him a powerful voice in America’s national politics for decades.

© 2025 Ray Hill