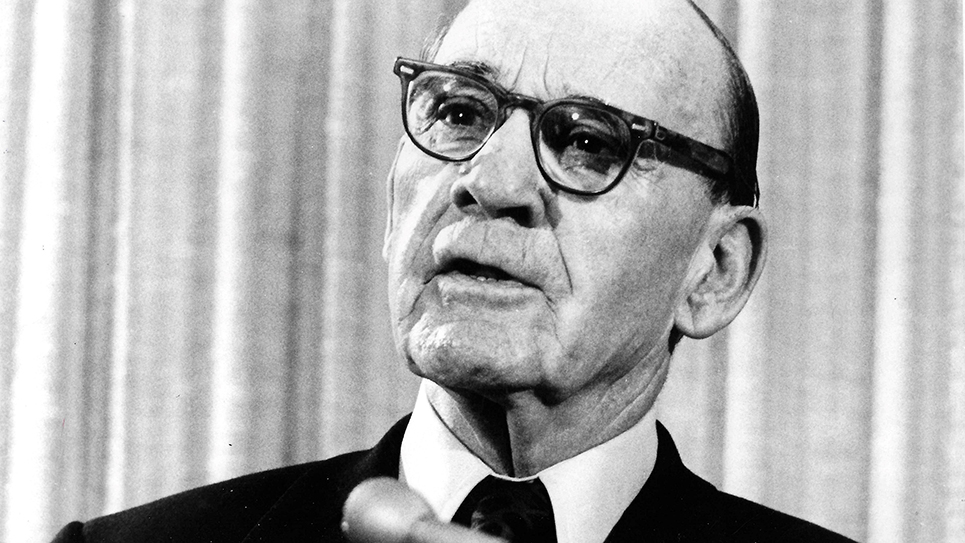

Senator K. D. McKellar with his friend and political partner, E. H. Crump. From the author’s personal collection.

The political partnership of U. S. Senator Kenneth McKellar and Memphis Boss Ed Crump had made them the masters of Tennessee politics by 1933. The correspondence between the two was voluminous, as they discussed appointments, political developments and strategy. The correspondence, which had once been addressed to “Mack” and “Ed”, had evolved to “Senator” and “Mr. Crump”, although McKellar frequently addressed Crump as “Ed”. Still, the two were warm personal, as well as political friends, and they socialized together. McKellar and Crump both had a passion for horse racing and both loved attending the yearly Kentucky Derby.

The occasional differences that arose between the two men was frequently the stuff of rumors and gave opponents fresh hope of a permanent rupture in their partnership. K. D. McKellar was perfectly capable of handling his end of any argument and the Memphis Boss knew it. McKellar possessed a legendary temper and Crump knew all too well the senator, even into his dotage, was prone to use his fists or even his cane when thoroughly angry. The late W. R. Davidson, McKellar’s last Administrative Assistant, related a tale of a meeting between Senator McKellar and Boss Crump during which the conversation went from being a bit pointed to rather heated. The old senator raised one of his hands, alarming the Memphis Boss who threw up his own hands in front of his face and shrieked, “No! No!”

Today politicians do their best to placate angry or unreasonable constituents. McKellar did not hesitate to tell voters he disagreed with them nor did he balk at replying to a constituent writing what he considered to be an abusive letter in kind.

Ed Crump was also very well aware of the power and influence McKellar had accrued in Washington, D. C. Crump had decided to go to Congress himself in 1930, displacing incumbent Congressman Hubert Fisher, who was a good friend of McKellar’s.

Fisher had served as U. S. Attorney for the Western District of Tennessee, an appointment McKellar had helped to arrange. When McKellar was first elected to the United States Senate, Fisher ran for and won McKellar’ seat in Congress. Fisher had served in the U. S. House of Representatives for fourteen years and was growing increasingly deaf by 1930. Crump’s announcement he was running for Congress foreclosed any hope Congressman Fisher had of running again and he wisely chose to retire. Crump served only two terms in Congress and found he did not especially like Washington, D. C. Crump was quite close to his family, operated a large and successful business in Memphis, and soon discovered that as a freshman member of Congress, he wielded no particular influence. For one with Crump’s out-sized ego and sense of self-importance, it had to come as something of a shock he was just another Congressman in the nation’s Capitol, although Kenneth McKellar possessed both enormous power and prestige in Washington, D. C. Crump realized the McKellar organization, unlike the Shelby County machine, spanned the length and breadth of Tennessee. McKellar had done countless favors for literally many thousands of Tennesseans; in fact, there seemed to be hardly a resident of the State of Tennessee for whom the senator had not done a favor. There were McKellar men in all ninety-five of Tennessee’s counties, all of whom maintained ties to Senator McKellar, as well as constant communication. McKellar routinely relied upon his contacts in each county to forward information and recommendations on the many appointments at his disposal. Crump saw first hand just how powerful and important McKellar was in Washington and understood the senator’s importance to Tennessee. Friendship aside, Crump knew no one could do more for Tennessee.

Senator McKellar had not been at all pleased with Crump’s rough treatment of his old friend Hubert Fisher. Another point of disagreement between the two men involved McKellar’s brother, Clint. Clint McKellar had been the Assistant Postmaster of Memphis for a good many years when the incumbent Postmaster died. McKellar proposed his brother for promotion as Postmaster of Memphis. Crump immediately complained, saying Clint’s appointment would be viewed as nepotism. It was not a charge that bothered Senator McKellar in the least, as well as a curious complaint from Crump in view of the fact the Memphis Boss was well aware McKellar’s Secretary was his youngest brother, D. W. “Don” McKellar. In fact, Don was married to another McKellar staffer, Janice Tuchfeld McKellar. When McKellar bothered to respond to anyone noticing he employed his brother, the senator replied Don was the best Secretary any senator had and there is every reason to believe McKellar was right. Don McKellar was very effective and was especially good at keeping up with anything pertaining to Tennessee and Tennesseans. Don, being McKellar’s youngest brother, could and did say things to the senator’s face others would have avoided.

McKellar responded to Crump’s complaint about promoting Clint McKellar by pointing out his older brother had long been a postal employee and had worked his way up through the postal service. Senator McKellar said Clint merited the promotion as Postmaster and simply because Clint was his brother was no reason to deny him something he had earned. McKellar made the appointment and Clint McKellar duly became Postmaster of Memphis over Crump’s objections.

Those who were hopeful the disagreements between McKellar and Crump would end their alliance were disappointed. Crump decided to retire from Congress in 1934 and selected Walter Chandler to succeed him. Governor McAlister was running for reelection and Senator Nathan L. Bachman was to face the voters to complete the rest of Cordell Hull’s term. McKellar himself was also up for reelection to another six-year term.

Congressman Gordon Browning of Huntingdon, like many another ambitious Congressman, had long wanted an opportunity to serve in the United States Senate. Browning had been in Congress since 1923 and by 1934 was eager to move up and began seeking support for a Senate bid. The unwritten rule of Tennessee politics at the time was senators should come from different sections of the state, which ensured no one section would have both senators. Bachman was from East Tennessee and McKellar from West Tennessee. Gordon Browning was himself from West Tennessee and initially he sought support to challenge McKellar. It was not long before McKellar heard the rumblings about Browning possible candidacy. McKellar prepared himself for a challenge from Congressman Browning, telling friends he was ready to give Browning “both barrels” in the event Browning was a candidate.

In the meantime, McKellar addressed a national audience on the radio at the beginning of 1934 to defend the New Deal’s regulations imposed upon big business. McKellar had loyally supported virtually every aspect of Franklin Roosevelt’s legislative program, although the Tennessee senator refused to back cutting the salaries and pensions of Federal employees. It was to be much later that Senator McKellar showed considerable independence of President Roosevelt.

McKellar closely monitored Gordon Browning’s progress and was not surprised when the Congressman finally decided against challenging him. Browning later confessed he could not garner a single commitment of support from a prominent person in Tennessee to run against Senator McKellar. Like McKellar, Gordon Browning was a stubborn man and he was determined to run for the United States Senate. Rather than challenge the venerable McKellar, Browning concluded he would have a better chance of success in running against Nathan L. Bachman. Senator Bachman had been appointed rather than elected to his Senate seat and had run a poor third in his previous try for the office in 1924.

Gordon Browning was an excellent speaker and masterful campaigner and was a real threat to Senator Bachman. McKellar had no real opposition in the Democratic primary and openly backed his junior colleague. In fact, some complained the Bachman campaign was being run out of McKellar’s Senate office.

Despite the largesse of the New Deal, in 1934 many Tennesseans were still suffering, especially farmers. Income derived from one of the chief cash crops, cotton, had fallen seventy-percent from 1929 – 1932. Cotton was selling for six cents per pound in 1933. While the Congress responded to the plight of cotton farmers with the Agricultural Adjustment Act and the Bankhead Cotton Control Act, one segment of American society had already grown tired of the New Deal by 1934. Businessmen were complaining vociferously about the regulations imposed by the New Deal. Poverty and unemployment were still persistent problems in Tennessee.

McKellar’s opponent in the 1934 primary was Dr. John R. Neal, a true eccentric and political gadfly. Dr. Neal charged McKellar with nepotism, but Senator McKellar refused to acknowledge Neal’s existence, much less his campaign. Neal cried that McKellar had made himself the “dictator” of Federal patronage in Tennessee. Former Governor Ben W. Hooper, whom McKellar had defeated eighteen years before to win his seat in the Senate, campaigning for the Republican senatorial nomination, repeated some of the charges made against the senator by Dr. Neal.

Senator McKellar did not especially like the grueling tours associated with campaigns and frankly confessed, “I don’t like hot weather,” did not bother to open a statewide headquarters during the primary election. McKellar even refused campaign contributions during the primary campaign, as he did not anticipate incurring any real expenses.

The 1934 election would be the first opportunity opponents had to test the strength of the McKellar – Crump combine and it would prove to be decisive.