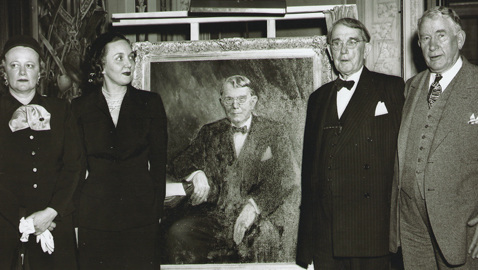

Senator K. D. McKellar (second from right) with Vice President Alben Barkley at the unveiling of his portrait as Chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee. Photo from the Nashville Banner Archives, the Nashville Public Library.

Kenneth McKellar, Tennessee’s eighty-year-old senior U. S. Senator, had resumed his positions of power and influence inside the Senate. His relations with his new and younger colleague, Estes Kefauver, had not improved. The origin of the dispute had occurred when Kefauver, evidently anticipating the election of Republican Thomas E. Dewey instead of Harry Truman, had recommended the appointment of a new U. S. Attorney for Memphis. Not only was Memphis McKellar’s home city, but worse still Kefauver had recommended the appointment of a Republican. Kefauver had not consulted with McKellar before making the recommendation and was likely embarrassed when it became apparent he clearly believed President Truman would be defeated.

McKellar and Kefauver would spar over appointments, as well as legislation for the next several years. When Kefauver submitted a bill creating a new judgeship in Tennessee, McKellar countered with his own legislation and Kefauver was humiliated when the Judiciary Committee, of which he was a member, endorsed the McKellar Bill. McKellar pressed his case on the Senate floor and was again victorious.

Senator McKellar’s announcement he had reconsidered his previous statement that he was “out of politics” did not lessen the interest of some in his Senate seat. Governor Gordon Browning had long cherished ambitions to serve in the United States Senate and he had not entirely given up on the notion of running for the Senate. Congressman Albert Gore, Sr. had his eyes on the McKellar seat and when Tennessee lost a seat in the House of Representatives following the 1950 census, Gore’s seat was eliminated as it was believed he was a certain candidate for the U. S. Senate in 1952. Indeed, following redistricting, Gore stepped up his appearances all over the state. Browning and Gore had been very close politically; Gore had even served in Browning’s first gubernatorial administration as Commissioner of Labor. When Browning had run for the U. S. Senate in 1934 against incumbent Nathan L. Bachman, Gore had been his campaign manager. The two men parted company over the possibility of running for the U. S. Senate. Browning, who had frequently tangled with McKellar, was wary of directly challenging the old senator, but concluded if McKellar retired, he would run for the Senate in 1952. Gore remained focused on running for the Senate in 1952 regardless of whether the Senator chose to retire or run for reelection.

McKellar finally ended the speculation about his political plans in June of 1951, sending out an announcement that “God willing” he would be a candidate to succeed himself. McKellar’s Senate office was flooded with letters from constituents praising his long service and promising support for a campaign, but his announcement was not greeted with universal approval. LIFE magazine, another of Henry Luce’s publications, published an editorial urging Tennesseans to retire McKellar. TIME magazine, also owned by Henry Luce, had never had anything kind to say about Kenneth McKellar, and listed the Tennessean amongst its list of “most expendable” members of the United States Senate.

Janice McKellar, the widow of the Senator’s youngest brother and one of his secretaries, recalled being in McKellar’s personal office when a call came from Tennessee. A close friend of McKellar’s was on the phone and told the Senator he should retire and if he did not retire, he would be defeated.

Senator McKellar softly replied, “There is no shame in defeat.”

Many appointees, relying upon Kenneth McKellar for their own tenure in office, had strongly urged him to run again, yet other friends, realizing McKellar was increasingly ill and slowing down, urged him not to run again, including Memphis Boss E. H. Crump.

Crump gently tried to counsel McKellar to step down from the Senate at the end of his term and retire gracefully. Crump knew his own political organization in Memphis had been seriously weakened by the 1948 election. There were clear signs many business and social leaders in Memphis were tiring of Crump’s long rule. Estes Kefauver had directly challenged Crump’s mastery of Memphis and had won a surprisingly large number of votes in Shelby County. Crump was again challenged by a group of reform candidates and the Boss quickly demonstrated he was still potent when his own ticket crushed the reformers, but Crump knew his control was slipping away.

Tennessee was changing, as was the entire country in the post war period. America was engaged in yet another war, this time in Korea. Many veterans of World War II had returned home determined to make a difference and the long domination of Tennessee politics by the McKellar – Crump combine was wearisome. The largely self-inflicted defeat suffered by the McKellar – Crump organization in 1948 gave hope to opponents that McKellar himself could be beaten in 1952.

Like many aging incumbents, McKellar watched helplessly as many of his strongest and oldest friends were incapacitated by age or died. McKellar’s frequent illnesses and legislative duties kept him in Washington, D. C. for so long his trips home to Tennessee were becoming less often. There was an entire generation of Tennesseans for whom McKellar was merely a name and they had never even seen their senior United States Senator.

Still, McKellar retained enormous influence in Washington and the Senate. Illinois Senator Paul Douglas wrote in his memoirs that McKellar’s “great hour” came each year as the Tennessean presented the Appropriations bill, which Douglas felt was a bit too generously larded with pork. A professor of economics by profession and a proud liberal, Douglas’s distaste for the pork barrel led to an experience with Kenneth McKellar he apparently never forgot. Taking occasion to question the Appropriations bill presented by Senator McKellar, Douglas made a speech deriding those projects he perceived to be political pork. Douglas spoke eloquently as he decried various projects as McKellar glared at him balefully from his own seat on the Senate floor. McKellar got to his feet following Douglas’s speech and promptly offered to ease the conscience of his colleague and moved to strike out every Federal dollar appropriated for Illinois.

Douglas was stunned and apparently did not consider Federal money for his own state to be either necessarily pork or a waste of taxpayer dollars. Everett Dirksen, Douglas’s Republican colleague from Illinois (and father-in-law of Tennessee’s future U. S. Senator Howard Baker) had to beg the wily old Tennessean not to withhold Federal money from the Land of Lincoln. McKellar finally agreed to Dirksen’s request, but not before the upstart professor had been both embarrassed and taught a lesson in practical politics.

Despite McKellar’s precarious health and advancing years, his power was still important to Tennessee. McKellar’s last Administrative Assistant, W. R. Davidson, related a meeting between Senator McKellar and members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff for the Armed Forces. The military brass awaited Senator McKellar with an elaborate map of the United States decorated with colorful pins dotting various locations across the country; each pin indicating a project where the military was spending Federal dollars. Davidson accompanied the elderly senator into the room and McKellar proceeded to peer at the map through his glasses, leaning heavily upon his cane. McKellar turned to face the gathered generals who waited expectantly. Senator McKellar uttered not a single word and angrily rapped the map with his cane, denoting the State of Tennessee, which ironically had no new colorful pin appended to it. Senator McKellar left the expectant and surprised generals without a word and hobbled off. McKellar’s power was such that he didn’t have to say anything. The generals, quickly discerning the cause for Senator McKellar’s wordless yet nonetheless expressive unhappiness, moved to rectify their mistake. They decided Tennessee might be a mighty fine location for the wind tunnel, a most happy event for the City of Tullahoma.

McKellar’s legendary temper was likely exacerbated by oftentimes not feeling well. The press duly noted any occasion Senator McKellar was ill, subtly reminding Tennesseans of his age and infirmity. McKellar had been absent from his office for several weeks when he had suffered serious burns after having fallen into a bath filled with scalding water while in Memphis. McKellar was confined to Memphis’s Baptist Hospital and assured inquiring reporters the burns on his shoulder, thigh and side were not serious and he would soon be leaving for his Washington office. Senator McKellar claimed his physicians declared the burns were “more painful than serious.”

Senator McKellar had fainted while sitting in the presiding officer’s chair once during the 1940s and suffering from increasingly painful rheumatism, leaving him oftentimes unsteady on his legs. McKellar suffered another fainting spell in the Senate chamber at his desk. Majority Leader Alben Barkley and Senator Tom Stewart of Tennessee helped McKellar to the Senator’s reading room where he was laid on a sofa. McKellar lapsed briefly into unconsciousness, but revived a short time later, wondering what had happened. Another spell in June of 1950 occurred when Senator McKellar had just left the Senate chamber and collapsed. Senators Burnet Maybank of South Carolina and William Knowland of California rushed to assist the old Tennessean, as did a Capitol police officer. They managed to take McKellar to the office of the Senate Sergeant At Arms, where he rested briefly as reporters were told McKellar had merely fainted. McKellar’s office, all too well aware of the possible repercussions back home, quickly issued a denial that McKellar had fainted. McKellar had not been out of the hospital long where he had been confined with a severe and persistent cold. The McKellar office explained the senator’s knee had buckled and he had fallen. According to the McKellar office, the Senator had not fainted.

Each report of Senator McKellar’s various ailments and infirmities only raised more questions about his fitness to serve another six-year term at an advanced age. The issue of age was a determining factor in Kenneth McKellar’s last campaign for the United States Senate.