Once again happily married, doting on his newborn daughter, former United States Senator Luke Lea concentrated upon reducing his indebtedness after his return from the World War. Frequently discussed as a potential candidate for high office, Lea made no move to seek election, but he was becoming more and more influential in Tennessee politics. The machine in Davidson County and Nashville was headed by Mayor Hillary Howse, which generally had the editorial support of E. B. Stahlman, publisher of the Nashville Banner. One of the most important men in the Nashville machine was attorney K. T. “Kit” McConnico. Once upon a time, Lea and McConnico had been warm friends, but McConnico’s ties to the Nashville machine, which Lea opposed, not only eventually ended their friendship, but also made them arch enemies. Lea had refused to support Governor A. H. Roberts for renomination in the 1920 Democratic primary. Roberts had managed to alienate a large number of groups and people during his single two-year term as governor and Lea backed William R. Crabtree, the former mayor of Chattanooga. Lea’s opposition to Governor Roberts did not cause the chief executive to lose the primary, but he did lose the general election to Republican Alf A. Taylor.

Lea was more successful two years later when he supported Clarksville attorney Austin Peay for the governorship. Peay only barely won the Democratic primary over seventy-seven-year-old former governor Benton McMillin, but he defeated Governor Alf Taylor in the general election by a decisive margin. Lea’s influence with Governor Peay was immense. While Governor Peay was certainly independent-minded, Luke Lea likely had more influence with Peay than most.

Austin Peay began his first administration by reforming all of state government. He consolidated an unwieldy structure into one more accountable and efficient. Where the governor once was at the mercy of the legislature and departments and agencies frequently operated outside the control of the chief executive, Peay’s reforms significantly strengthened the governor’s office. Peay also brought the state budget directly under the governor purview.

Lea’s friendship with Governor Peay was hard not to notice; the governor and his family were frequent guests for supper at Lea’s home on Sunday nights. When the governor imposed a luxury tax on tobacco, the tobacco industry responded by refusing to advertise its products in Lea’s newspaper, the Nashville Tennessean.

Governor Peay, although a relatively youthful man, was in somewhat delicate health. The governor had gone to rest at a sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan for a heart condition. Lea’s biographer quotes from a letter sent by the governor which references the infamous Scopes Trial in Dayton, Tennessee. Peay’s mention of the “abominable Dayton trial” went on to acknowledge the governor was “suffering over those two death cases,” involving men condemned to death. Peay concluded, “It is worth all it has cost being Governor two terms to know you and your wonderful family.”

A brittle alliance between the governor and E. H. Crump, leader of the Shelby County machine, was beginning to fray at the edges. Crump thoroughly disliked Luke Lea and was never comfortable in an alliance which included the former senator. Crump was also unhappy with Governor Peay’s taxation policies, which collected the money where it was, the urban areas of the state, and spent the proceeds in the rural areas of Tennessee. Crump was less than enthused about the notion of Peay running for a third consecutive two-year term in 1926. The Memphis Boss also suspected if reelected again in 1926, Peay might decide to challenge Senator K. D. McKellar in 1928, a thought that had also crossed the senator’s mind. The temporary alliance came to an end with the 1926 elections.

Both Crump and Senator McKellar opted to support State Treasurer Hill McAlister to run against Governor Peay. McAlister was something of an underwhelming candidate, although apparently quite competent. McAlister also drew the support of the Nashville machine, which was opposed by Luke Lea and his Tennessean.

It was a hard fought campaign inside the Democratic primary and McAlister proved to be quite strong in Tennessee’s urban areas. Governor Peay maintained his hold on rural Tennessee and carried East Tennessee, where his support for the Great Smoky Mountain National Park was highly popular. Peay won renomination by some eight thousand votes. Peay’s appeal in East Tennessee was not limited to the governor’s support for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park; Peay had seen to it that East Tennessee was treated fairly in the distribution of new roads and had been a strong supporter of higher education, which benefitted the University of Tennessee. Winning almost seventy percent of the vote in East Tennessee, it accounted for the governor’s winning margin in the primary. Peay’s popularity in the eastern part of the state helped him to win the region in the general election.

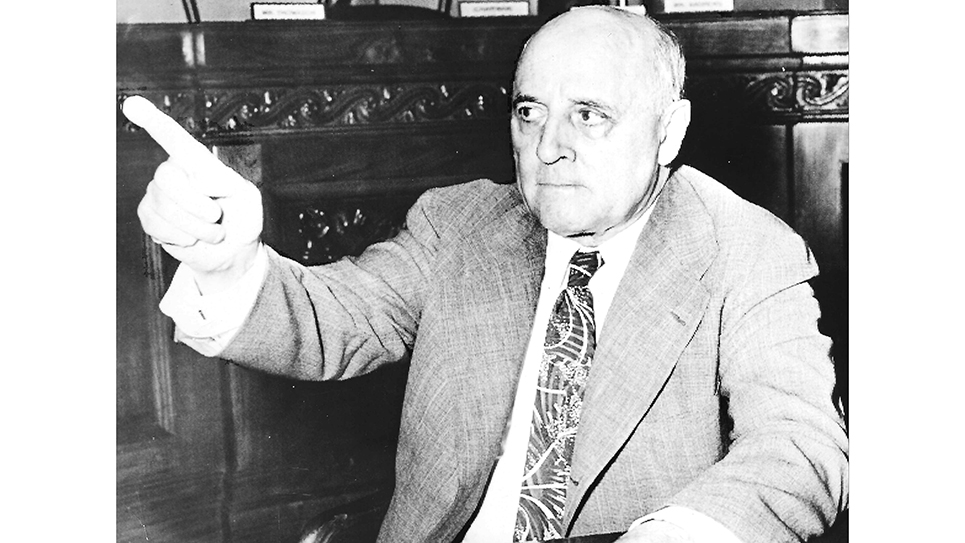

Peay was stricken with a serious heart attack during the legislative session and the General Assembly took off for six weeks to allow him to recover. Relations between the governor and the legislature had deteriorated along with Peay’s health. When the General Assembly increased the tax on gasoline, Governor Peay vetoed the bill. It appeared that the governor’s veto might be overridden and Luke Lea appealed to Congressman Gordon Browning of Huntingdon for help with a particular state senator in Browning’s home county of Carroll. According to Lea’s biographer, the senator very reluctantly agreed to veto to sustain Governor Peay’s veto if Browning were to accept the blame or credit for his vote, depending upon one’s view. Browning sat on the floor of the Tennessee State Senate that evening and just so no one would mistake the reason for his switch, the senator pointed to Browning as he cast his vote.

It was one of Austin Peay’s last victories as governor. Peay died from a cerebral hemorrhage on October 2, 1927. Luke Lea was one of the governor’s pallbearers.

Henry Horton, Speaker of the State Senate and Lieutenant Governor, became the acting governor of Tennessee. A state senator and farmer from Marshall County with little political experience, Horton turned to Luke Lea as his mentor and advisor, a role the former senator happily accepted. It was during the administration of Governor Henry Horton that Luke Lea reached the apex of his political influence in Tennessee. It would also be the cause of his own political, personal and financial ruin.

Unlike Austin Peay, Henry Horton had no particular scruples about using state projects and money to his political advantage. Also unlike Governor Peay, Henry Horton had little ability to reject Lea’s advice. Peay had been both high minded and independent, while Henry Horton was neither. With the 1928 election fast approaching, it became quite clear that Horton intended to run to succeed himself and it was also equally clear that the Crump machine and that of Hillary Howse in Nashville would field a candidate to oppose the governor in the Democratic primary.

Once again, Crump and Howse chose to back former State Treasurer Hill McAlister for the gubernatorial nomination. Luke Lea had been expanding his newspaper empire, which not only included the Nashville Tennessean, but the Knoxville Journal and the Memphis Commercial Appeal as well. With newspapers in each of Tennessee’s three grand divisions, especially at a time when there was no television and radio was not the widespread medium it would become a few years later, Luke Lea’s influence was enormous.

According to Lea’s daughter and biographer, Mary Louise Tidwell, the former senator even attempted to purchase the Kansas City Star when the newspaper became available for purchase following the death of its owner. Lea’s former secretary, John D. Erwin, told Tidwell Lea had left Kansas City believing he had negotiated a deal to purchase the Star for $10 million. The paper’s trustees, however, preferred local ownership and accepted a higher offer, deeply disappointing Luke Lea.

To raise the money needed to buy the newspapers, Lea had become acquainted with Rogers Caldwell of Caldwell and Company. The enterprising Caldwell had believed a company floating bonds to provide funds for ventures would be profitable and help to expand business in the South. Caldwell helped to provide the much needed capital for Lea’s expansion of his Tennessee Publishing Company.

As Luke Lea expanded his business empire, he made a gift to Nashville through several hundreds of acres of land he owned near the Belle Meade Country Club. Lea’s gift was to be used as a public park and was named for his father-in-law Percy Warner after he died in 1927.

The 1928 Democratic primary for governor was a brutal affair and Governor Henry Horton managed to win the nomination. Hill McAlister’s appeal inside the urban areas was still strong, but like the late Austin Peay before him, Horton managed to do quite well in the rural areas.

The crafty Lea had conceived of a means to divide the resources, time and attention of E. H. Crump by encouraging a candidate to challenge Crump’s warm personal friend and political partner, Senator Kenneth D. McKellar. Congressman Finis Garrett of Dresden was the Minority Leader in the U. S. House of Representatives. Despite being a Democrat, Garrett was thoroughly conservative and considered the more liberal McKellar as quite nearly a socialist. Lea backed Garrett’s candidacy and it did indeed achieve its purpose of keeping McKellar busy with his own campaign and dividing the resources of the Crump machine.

Senator McKellar, highly popular in Tennessee, turned back Garrett’s challenge, winning renomination by a two-to-one margin. Yet, Henry Horton only scraped by to win a term in his own right as governor of Tennessee.

Luke Lea had reached the zenith of his political influence in Tennessee.