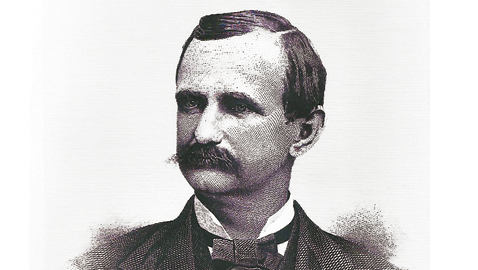

For more than a decade Leonidas Campbell Houk was the Congressman from Tennessee’s Second District. A man with neatly combed hair and a mustache that would have done justice to a Victorian villain; Houk was a popular political figure who tightly maintained his control of his district for years.

Houk was born June 8, 1836 near Boyd’s Creek and like many of his contemporaries, his childhood was abbreviated by the loss of his father at an early age, which impoverished his family. L. C. Houk was almost entirely self-educated, being a voracious reader. Eventually, Houk became proficient at cabinet making but found himself in trouble with the law at age seventeen and found himself in court for having discharged a firearm within the City limits of Maryville. During Houk’s trial, Oliver Perry Temple, a highly respected local attorney, while not officially defending Houk, jumped to his feet and made an oration praising Houk. Temple’s speech helped to convince the presiding judge to show the young man leniency. As a result of his trial, Leonidas C. Houk became quite interested in the law and regularly visited Mr. Temple’s office to chat and borrow legal books. The friendship between Oliver Perry Temple and Lenonidas C. Houk would continue until the end of the Congressman’s life.

Again self-educated in the field of law, Houk commenced to practice as an attorney in 1859. The Civil War erupted two years later and Houk, like most of his fellow East Tennesseans, was a strong supporter of the Union cause. Houk debated Henry S. Foote, a former United States senator and governor of Mississippi, defending the Unionist point of view. Eventually Houk traveled to Kentucky to enlist as a private in the Union Army. Houk rose to the rank of Colonel and found himself badly outnumbered while fighting in Kentucky. Refusing to surrender, Colonel Houk chose to lead his men in a fighting retreat. The retreat was a brutal affair and Houk’s health began to falter, leading to his quitting the Union Army in 1863.

As his health improved, Houk continued his support for the Union, largely through penning articles on behalf of the Union cause. Houk was an elector for the Union Party candidates in 1864 and strongly supported Abraham Lincoln and his running mate Andrew Johnson.

Houk entered the primary to win Tennessee’s Second Congressional district in 1865, but was defeated by Horace Maynard. Houk recovered from his loss by being elected judge of the Circuit Court for Tennessee’s Seventeenth District. Houk enthusiastically supported the policies of governor William G. “Parson” Brownlow, which were quite harsh toward former Confederates, whom Brownlow insisted be disenfranchised. Houk again challenged Congressman Horace Maynard for the Republican nomination for Congress in 1868 and lost. It was a bitter battle and Houk, severely disappointed by his defeat, changed his mind about his support for Brownlow. Houk moved from Clinton in 1869, relocating in Knoxville where he formed a law firm with Henry R. Gibson, who would go on to be elected to Congress himself, defeating Houk’s son John.

Houk sought election to the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1872 and was elected, but served only the one term as the stubborn candidate decided to run for Congress again in 1874 as Horace Maynard was not seeking reelection. Houk engaged in a hard fought campaign with Jacob Thornburgh, which proved to be very bitter. Houk finally withdrew as a candidate, finding his candidacy might harm Republican chances in the general election.

The persistent L. C. Houk finally realized his ambition and claimed the GOP nomination for Congress in 1878 when he beat William Rule. Rule was the editor of the Knoxville Chronicle. Rule had been associated with William G. Brownlow and when the Knoxville Whig had been sold and the new owner tried to turn it into a Democratic paper, Rule had quickly started the Chronicle to keep the Republican cause alive. Rule’s facility with a pen caused a near fatal encounter on Gay Street with James W. Wallace, editor of the Knoxville Tribune.

Wallace strongly objected to what he considered a personal insult contained in the pages of the Knoxville Chronicle and demanded Rule issue an apology. Rule refused to apologize and the argument escalated with Rule clubbing Wallace with his cane. The battered and infuriated Wallace responded by pulling out a pistol and rapidly fired off three shots, all of which fortunately missed Rule. The altercation between the two editors caused both to be arrested, although ultimately no charges were filed by either party. The two partisan editors blamed the other for the fracas and local Republicans, pleased with Rule for having attacked Wallace, gave him a new walking stick.

Houk only barely managed to beat William Rule, but they were later able to heal the differences between them. Rule’s newspaper eventually became the Knoxville Journal and the Journal was perceived by many to be the editorial mouthpiece for Congressman Houk’s political organization.

Houk quickly perceived his constituents were less interested in the pressing national issues of the day than local issues. Congressman Houk thought little of becoming a national statesman, but concentrated on providing good constituent service and strengthening his hold on the Second District. Houk extended aid to veterans, both Union and Confederate, at a time when there was no Social Security and national pensions were granted by a special act of Congress. Houk routinely distributed seeds from the Department of Agriculture to grateful constituents. Congressman Houk also busied himself with seeking compensation for those constituents who had suffered extensive property damage during the Civil War.

Houk and his old rival William Rule once again were feuding in 1881 when Rule wanted to be Knoxville’s Postmaster, a choice political plum at the time. Houk intended to keep his hold on his own political patronage and supported Oliver Perry Temple, the lawyer who had spoken up for him during his trial, for the postmastership. When denied the postmaster’s job, Rule once again ran for Congress against Houk in an especially hard fought campaign that left both men claiming to be the Republican nominee. The issue was finally decided in the general election, which Congressman Houk won easily. That election apparently finally decided the issue between Houk and William Rule and Rule’s newspaper eventually became part of the Houk machine. Houk’s last victory over Rule also helped to deter future opposition to his continued incumbency.

Congressman Houk consolidated his power, not only inside his own district, but successfully maneuvered to gain control of all patronage in the State of Tennessee. There was considerable patronage to distribute through a Republican president and Leonidas C. Houk became more or less the most important member of the GOP in Tennessee. Through his control of patronage, Congressman Houk forged an alliance with Tennessee Democrats who hungered for some of the appointments available through the federal government. At least one other Republican found fault with Houk’s arrangement with the Democrats. Congressman Henry Clay Evans of Chattanooga believed Houk was too quick to give Democrats what they wanted and the two engaged in a bitter fight over control of Republican patronage. The state legislature had control over redistricting Congressional seats and Houk doubtless quietly encouraged Democrats (who controlled the legislature) to help ease H. Clay Evans out of Congress. It worked. Having to run in a much altered district, Evans lost his reelection bid, but the feud between the two men continued even after Congressman Houk’s death when Evans fought with Houk’s son John.

Leonidas C. Houk was only fifty-four years old at the time of his death and the Grim Reaper found the Congressman in a most unusual way. Congressman Houk visited DePue’s Drug Store where he proceeded to drink a bottle of arsenic. From all the information available, Houk was not suicidal and it seemed to be a bizarre accident. Houk suffered terribly and died the next day in agony.

Congressman Houk was buried with much fanfare and was succeeded in Congress by his son, John Chiles Houk. The younger Houk had worked as a clerk in the Pensions Bureau in Washington, D. C. under his father’s patronage while studying the law at what later became George Washington University. He had also been an Assistant to the Doorkeeper of the United States House of Representatives and secretary to the Tennessee Republican Executive Committee, both jobs he acquired through the influence of his father.

By the time of his father’s death, John C. Houk was practicing law in Knoxville. The beneficiary of both great sympathy due to his father’s death, as well as the political strength of the Houk machine, John C. Houk was elected to take his father’s place in Congress.

John C. Houk was reelected in 1892, but defeated for renomination in 1894 by Henry R. Gibson, who had once been his father’s law partner. Houk did not quit politics after his defeat for reelection to Congress; he was elected to the Tennessee State Senate in 1896. Houk would serve, off and on, in the State Senate until his death on June 3, 1923. John Houk was a member of the State Senate at the time he died.

John C. Houk’s passing marked the end of the Houk political dynasty.