By Ray Hill

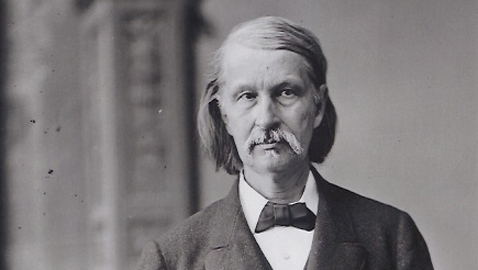

There are quite a few things named for Horace Maynard in our community, not the least of which is Maynardville. Yet, few people seem to recall Horace Maynard, who was one of the masters of Tennessee’s rough and tumble politics before and after the Civil War.

Horace Maynard was, at one time or the other, a successful politician, diplomat, lawyer, educator and briefly, jurist.

Maynard was not a native Tennessean, having been born in Westborough, Massachusetts August 30, 1814. Maynard entered prestigious Amherst College and promptly displayed his sense of purpose as well as ambition when he put a large “V” above the door to his rooms. Nobody seemed to know exactly what the “V” meant and Maynard wasn’t telling, until he became the class valedictorian. Just after graduating from Amherst, Maynard relocated to Knoxville, as he had accepted an offer to teach at East Tennessee College (which eventually became the University of Tennessee). Initially, Professor Maynard taught students at East Tennessee College’s preparatory program, which was essentially a high school class. Maynard soon won a promotion and began teaching college courses, specializing in ancient languages as well as mathematics.

The Massachusetts-born Maynard was not impressed with Knoxville. He considered it unrefined and anything but progressive. Horace Maynard considered leaving Knoxville, but after passing the Bar in 1844, he became quite successful in arguing cases in local courts and his dissatisfaction with Knoxville abated.

According to contemporaries who knew Horace Maynard at the time he began practicing law, Maynard did not have the sort of personality one would ordinarily associate with success in politics. Evidently Maynard could be quite short with people and was not a particularly genial sort of fellow. Horace Maynard regularly employed a well developed sense of sarcasm in dealing with his opponents in the courtroom and some described his personality as “pungent”. Despite his abrupt manner, Maynard won the respect of his colleagues, especially for being forthright. Even those who admitted they didn’t especially like Maynard claim to have voted for him because of his intellect and ability.

Maynard’s first bid for Congress was in 1853 when he challenged William Montgomery Churchwell, who was a native of East Tennessee, as well as a much-admired attorney and judge. Churchwell had first been elected to Congress in 1851 as a Democrat. Horace Maynard was thrashed by local newspapers who kept up a drumbeat of opposition to his candidacy. Churchwell must have been an exceptionally able young man, as he was first elected to Congress when only twenty-five years old. Churchwell is also the last Democrat to be elected to Congress from Tennessee’s Second District.

Maynard resumed his law practice and waited until 1857 when he again ran for Congress. William M. Churchwell’s successor in Congress was William Henry Sneed. Sneed had been a Whig, but with the Whig Party having deteriorated to nothing, he ran and was elected on the American Party ticket. Sneed refused to seek a second term, opening the door for Horace Maynard to run again.

This time Maynard had the support of the Knoxville Whig, which was the newspaper of William G. “Parson” Brownlow. Maynard won and was reelected two years later as a member of the “Opposition” Party. Maynard’s popularity inside his own district was increasing and he won nearly 70% of the vote in his first reelection campaign. Congressman Maynard won a third term in 1861 on the “Unionist” Party ticket. Maynard had won three elections with a different political affiliation each time.

Interestingly, while Horace Maynard was deeply opposed to secession, he was a slave owner. His father was an abolitionist and Maynard, despite his loyalty to the Union, was not above defending the practice of slavery. As Tennessee began to come apart at the seams during the raging debate on secession, Horace Maynard labored hard to keep Tennessee in the Union. Maynard spoke all across East Tennessee on behalf of the Union and against secession.

Maynard was in Washington, D. C. when Confederate forces occupied much of East Tennessee. Congressman Maynard begged President Lincoln to send Union troops to take East Tennessee back from the Confederates. Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, was also a strong Unionist and he and Congressman Maynard kept up the pressure although it was two years before Union troops entered Knoxville. Like many others in his situation, Horace Maynard’s property was confiscated by the Confederates and he was unable to return to his home in Knoxville.

Historian Natalie Sweet noted some correspondence to President Lincoln from Congressman Maynard outlining the plight of the people of East Tennessee. In 1862, Maynard wrote President Lincoln from Massachusetts, “Having provided for the freedom of the slaves, can you not, I beg you, in God’s name, do something for the freedom of the white people of East Tennessee?”

Maynard’s wife Laura also wrote to Lincoln, wondering “…perhaps you have a son – – – I have one in that little army at Cumberland Gap & many another mother’s son is there – – – Shall they be saved?”

Horace Maynard was finally able to come home and to his dismay, he discovered a serious rift between Unionists over the Emancipation Proclamation. Maynard did not run for Congress again, but accepted an offer from Andrew Johnson to serve as Tennessee’s attorney general. Johnson had been appointed military governor for Tennessee by President Lincoln and Johnson’s personal support for the Union eventually led to his being selected to run for vice president in 1864.

With Tennessee’s reentry into the Union, Maynard was again a candidate for Congress in 1866 and was elected. He was reelected in 1868 and Governor William G. Brownlow appointed Maynard to a vacancy on the Tennessee State Supreme Court. Maynard did not bother to resign from Congress, but continued to serve as both Congressman from the Second District and a Justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court.

My friend Donald Paine, himself an able lawyer and historian and former president of the Bar Association, has written an excellent article on the dilemma of Maynard’s service on the Tennessee Supreme Court and it is well worth reading, especially for legal scholars. Maynard did not remain on the court long and his limited participation was upheld as valid.

Tennessee, due to redistricting, was electing a Congressman-At-Large in 1872 and Maynard was the Republican candidate, facing former President Andrew Johnson, who was the Democratic candidate. B. F. Cheatham also entered the race as an Independent Democrat. Maynard won the election, which was a stinging defeat for Johnson. In fact, Johnson’s strong desire to return to elective office and vindicate his stormy tenure as president was frustrated until he eventually won a seat in the United States Senate. Few presidents have been abused as Andrew Johnson was and the former chief executive hoped the people who knew him best would give him the opportunity to serve yet again. Johnson’s triumph was abbreviated by his death from a stroke.

Having been elected statewide, Congressman Maynard was the GOP candidate for governor in 1874. Despite a vigorous campaign, Maynard lost to Democrat James D. Porter.

Maynard was not long out of office as he was appointed Minister to the Ottoman Empire in 1875 by President Ulysses S. Grant. Horace Maynard served for five years as Minister to Turkey until his appointment as Postmaster General during the administration of President Rutherford B. Hayes.

Maynard was still the Postmaster General when he died in Knoxville on May 3, 1882.

Horace Maynard’s death was completely unexpected. He had attended the Republican State Convention in Nashville earlier in the week and Maynard had been well enough to attend church the following Sunday and gave a lecture that same evening. Maynard was walking the streets of Knoxville on Monday and even entertained at his home until 10:00 p.m. that night. Later that evening Maynard began to experience chest pains, but refused to see a doctor or be taken to the hospital, claiming the pain would pass soon enough. Finally Maynard exclaimed, “I can’t breathe.” Those were his last words before dying.

Horace Maynard was remembered for his acerbic wit, his mastery of facts and was considered one of the ablest lawyers in Tennessee. It was Maynard’s ability as an attorney that caused Union County to name its county seat for him. Knox County had attempted to sue the newly formed Union County and the Union County fathers wisely employed Horace Maynard as their attorney. Until that time, the territory comprising Union County had been in Knox County. Maynard successfully defended Union County’s right to exist and in gratitude, Maynardville came to be the county seat.

There is still the Horace Maynard Middle School in Union County, which had once been the Horace Maynard High School. Although he has been gone for well over one hundred years, one can still see sprinkled through the obituaries a few aged men named for Maynard.

Despite his pungent and oftentimes abrasive personality, Horace Maynard made himself a force to be reckoned with through intellect and sheer hard work to win the respect and admiration of both friends and foes. It is not an easy feat to accomplish.