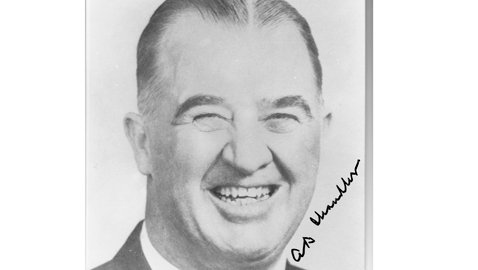

Few subjects excite as much commentary as politics and sports and Albert B. Chandler played a big role in both for decades. Serving as governor, United States senator and Commissioner of Baseball, “Happy” Chandler was an institution. Like most who stayed around long enough, Chandler became controversial in some aspects, but he also lived to an age where he enjoyed the status of not only an elder statesman, but also a living icon. A. B. Chandler would totter out into the spotlight at sporting events well into his eighties and roar out his rendition of “My Old Kentucky Home” and could bring tears to the eyes of not only oldsters, but youngsters as well. His appearances were referred to by sportscasters as “one of the most emotional moments in sports”.

Born in Corydon, Kentucky on July 14, 1898, Albert Benjamin Chandler would go on to excel as an athlete. Happy Chandler’s memory proved to be remarkably lucid as he approached his nineties. Chandler’s mother had apparently been an orphan and married at her first opportunity when she was but fifteen years old. She produced two boys within two years and found she was unable to deal with two young sons and fled. Happy Chandler recalled in his autobiography his mother’s leaving her family was his earliest childhood memory. Some years later, Chandler located his mother and discovered she had a new family.

Happy Chandler learned the value of hard work very early in life and was supporting himself at the tender age of eight through a paper route, as well as performing odd jobs here and there. While in high school, Chandler was an excellent athlete and was the captain of his baseball team. The future governor’s father had urged his son to go into the ministry, but Happy preferred to go on to college and entered Transylvania College, which is where he acquired the nickname that would stay with him until the end of his life.

Chandler played baseball, basketball and football, serving as captain of both the baseball and basketball teams and was the quarterback for the football team. Happy’s college career was almost interrupted when he tried out to join a professional baseball team, but he did not make the cut and completed his education. A. B. Chandler went on to the University of Kentucky to earn his law degree and coached high school athletics before graduating.

By 1924, Happy Chandler had his law degree in hand and the following year he married Mildred Watkins, who was a teacher. Their union produced four children, one of whom, Mimi, would star in a Hollywood movie with Dorothy Lamour before returning home to Kentucky.

Chandler was not nicknamed “Happy” for nothing and his early career was busy; not only did he practice law, but he found time to continue coaching and scouting, as well as joining numerous fraternal organizations.

It was not long before Happy Chandler found his true calling and was selected to chair the Democratic Committee for Woodford County. Shortly thereafter, Chandler was named to be the Clerk and Master for the Circuit Court. In 1929, Chandler ran for a seat in the Kentucky State Senate and won. A. B. Chandler was a regular Democrat and he joined with many of his colleagues to remove some of the executive powers granted the governor, due to the fact the unthinkable had happened and the people of Kentucky had elected a Republican governor.

Chandler’s rise to prominence was rapid and he was being mentioned as a candidate to run for Lieutenant Governor in 1931, only two years after his initial election to the Kentucky State Senate. Yet, Happy Chandler’s rise was not without obstacles. As is always the case in politics, alliances come together and come undone. Chandler faced opposition at the nominating convention from Jack Howard, who had the support of Congressman Fred Vinson, who would later go on to be Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. The thirty-three year old Chandler had the support of former Senator Johnson Camden and former Congressman Ben Johnson, who was still a power in Kentucky politics. The support of Johnson and Camden, along with a few other party bosses proved to be critical in Chandler’s nomination for Lieutenant Governor. The nominee for governor, Ruby Laffoon (certainly one of the more colorful names in political history) had also been the beneficiary of support from some of the more powerful party bosses, but he would come to loathe his lieutenant governor. The tangled alliances of the two men made them uneasy allies.

The Democratic ticket won easily, especially with the Great Depression still causing wide spread suffering throughout the Bluegrass State and the unpopularity of President Herbert Hoover. From the beginning of his term as lieutenant governor, it was clear A. B. Chandler was no ordinary politician. Unlike his predecessors, Chandler opened an office in the Capitol and worked full time as lieutenant governor. Previously, lieutenant governors had only been in Frankfort when the legislature was in session and went home. Despite the hard economic times, Governor Laffoon decided to implement a sales tax and to his astonishment, Happy Chandler announced his opposition to a sales tax. A bitter battle erupted between Kentucky Democrats; Chandler and the Speaker of the House of Representatives, John Y. Brown, managed to defeat the sales tax. An outraged Governor Laffoon insisted the lieutenant governor’s powers be trimmed back by the State Senate. The governor’s allies did just that and the sales tax passed by exactly one vote each in the House of Representatives and the State Senate. It was a pyrrhic victory for the governor, as the tax was predictably unpopular with the public.

Ruby Laffoon was a bald, rotund man who was forced to walk with the help of a cane due to having suffered an injury on the farm as a youth. Laffoon had been kicked by a mule, which fractured his hip and kept him in the hospital for weeks. Once out of the hospital, Laffoon slipped on a patch of ice and reinjured his hip. Laffoon’s administration was notable in one small respect; he named an astounding number of people as Kentucky “Colonels”, not the least of whom was Harland Sanders of Kentucky Fried Chicken fame.

Being quite ambitious, Happy Chandler never made any secret of his intention to run for governor when Laffoon’s term expired. That idea did not set any too well with Governor Laffoon, who had already hand picked his own successor. The governor had given his blessing to Thomas Rhea. Rhea had been State Treasurer for Kentucky, which was an elected position. Rhea also occupied a powerful post in the Laffoon administration as head of the State Highway Commission. Governor Laffoon had removed Ben Johnson to install Rhea as head of the Highway Commission; Rhea and Johnson were bitter political enemies and had supported opposing candidates for lieutenant governor in 1931.

Governor Laffoon confidently expected to name Thomas Rhea as the Democratic nominee in 1935, as he exercised considerable control over the State Democratic Committee and held the power of patronage throughout Kentucky. Unfortunately for Thomas Rhea, Ruby Laffoon underestimated Happy Chandler. Chandler realized his chances to be the Democratic gubernatorial nominee were slim to none if the contest were held in a nominating convention. The wily Chandler waited until Governor Laffoon traveled to Washington, D. C. for a conference with President Franklin Roosevelt. According to Kentucky’s Constitution, whenever the governor was absent from the state, the lieutenant governor was Acting Governor. The day after Laffoon left for Washington, D. C., Acting Governor A. B. Chandler called the legislature into special session to consider a bill to replace the nominating conventions with popular primary elections. Laffoon raced home and immediately contested Chandler’s call for a special session of the legislature, contending the lieutenant governor had no such authority. The Kentucky Court of Appeals disagreed and upheld Chandler’s call for a special session later that month. The best that Governor Laffoon could do, considering the popularity of allowing the respective parties to nominate their candidates for statewide office in primary elections, was to add a provision calling for a run-off election between the two candidates receiving the most votes.

Chandler immediately became a candidate for the Democratic nomination for governor and, as expected, faced Thomas Rhea in the primary. Happy drew enormous crowds, singing “My Old Kentucky Home” and was a colorful speaker. He derided Rhea as “Sales Tax Tom” and promised to repeal the tax if elected. Chandler preached against the combination of “Ruby, Rhea and Ruin” for Kentucky and ran second in the first primary.

Tom Rhea ran only about fourteen thousand votes ahead of A. B. Chandler in the Democratic primary, while two minor candidates siphoned off just over fifty thousand votes, leaving Rhea short of a majority.

Had Ruby Laffoon not insisted upon adding the provision for the run-off election, Thomas Rhea would have been elected governor.

Happy Chandler again faced Thomas Rhea in the run-off election and stepped up his attacks on both Rhea and the Laffoon administration. Happy promised a beleaguered people that not only would he repeal the hated sales tax, but would not increase property taxes and fight to reduce the gasoline tax. Chandler denounced the common practice by the Democratic machine of assessing public employees a portion of their salaries to pay for campaigns. Happy Chandler’s drive for the Democratic nomination received a boost when he received the endorsement of the two minor candidates who had run in the first primary. The momentum was with Happy and he won the nomination, defeating Tom Rhea by just over sixteen thousand votes.

It was a remarkable feat for Chandler to have opposed the state machine and win.

Yet the machine was not accepting the defeat gracefully. An enraged Governor Ruby Laffoon bolted the party to support the Republican nominee, King Swope (yet another colorful name).

King Swope had served a brief term in Congress, but lost his reelection bid in a year that was otherwise a Republican tidal wave. He was later elected to be a judge of the Circuit Court and would be the GOP nominee for governor again in 1939.

Swope had a very formal and rather forbidding exterior and Happy Chandler had great fun referring to the Republican as “his majesty”. Happy gleefully hung former President Herbert Hoover around Swope’s neck and that ball and chain was enough to sink the Republican’s candidacy. A. B. Chandler won the general election by just over ninety-five thousand votes. It was, up until that time, the most decisive victory won by any gubernatorial candidate in Kentucky history.

Once sworn in to office, Happy kept his word and set out to repeal the unpopular sales tax. The legislature quickly complied and Governor Chandler then demanded the legislature repeal the run-off provision in state primaries it had enacted under the administration of his predecessor. Once again, the legislature did as the governor asked.

Governor Chandler introducing sweeping reforms, reorganizing state government and replacing revenue lost through the repeal of the sales tax via other taxes, including an income tax. Powerful special interests had intended to induce their allies in the legislature to stall the governor’s reforms by delaying action until the legislative session expired. Once again, Happy Chandler’s enemies underestimated him. The governor had the legislature adjourn after only thirty-nine days in session, allowing Happy to call a special session which had no time limit on how long it could remain in session. The special interests were bereft of any way to kill Chandler’s proposals and they were adopted by the legislature.

Chandler’s reforms not only saved money for taxpayers, but allowed him to pay down the state’s debt significantly, as well as pump more money into education and other public services. Kentucky’s state colleges and universities received a windfall from Happy Chandler’s administration and it was Governor Chandler who provided free textbooks for Kentucky school children and created a pension fund for professional educators.

With his political success as governor, perhaps it was natural that Happy Chandler’s eyes began looking to Washington, D. C.