Click here to view this week’s Focus.

Race to the top

Part 3: Teacher Evaluations

By Sally Absher

sallyabsher@gmail.com

Some say it is just bringing transparency and accountability to the teaching profession. Others have called it a war on teachers. One thing is certain; the way teachers are evaluated, compensated, and even advance in their careers has changed drastically under Race to the Top (RTTT).

In order to be eligible for the coveted RTTT grants and No Child Left Behind (NCLB) waivers, states had to agree to use value-added modeling in teacher evaluations. Let’s start with a simple Wiki description of value added modeling, or VAM:

Researchers wanted a way to isolate the teacher’s contributions from those factors outside the teacher’s control that are known to strongly affect student test performance, including the student’s general intelligence, poverty, and parental involvement.

So they devised a “statistical process using a student’s past test scores to predict the student’s future test scores, on the assumption that students usually score approximately as well each year as they have in past years. The student’s actual score is then compared to the predicted score. The difference between the predicted and actual scores, if any, is assumed to be due to the teacher and the school, rather than to the student’s natural ability or socioeconomic circumstances.”

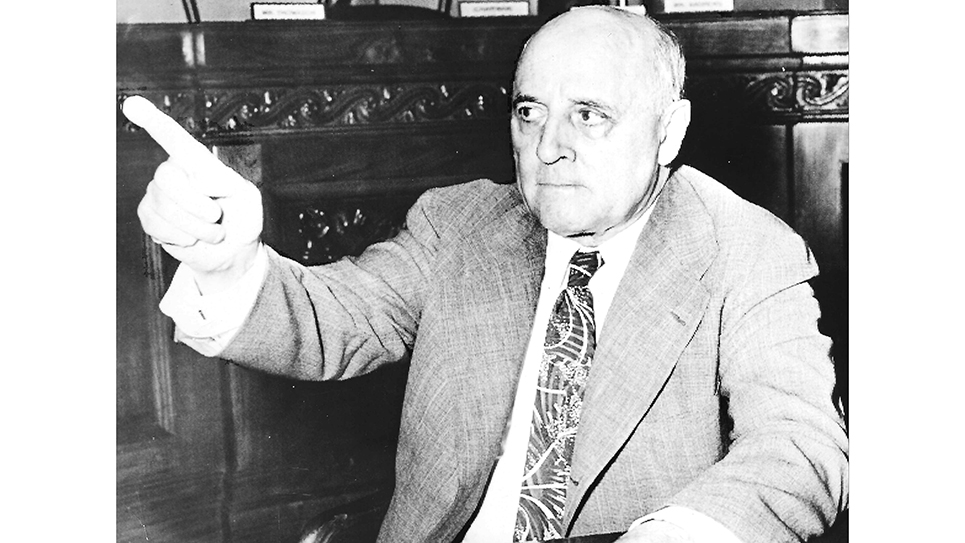

Statistician William Sanders is credited with developing VAM (also termed the value added assessment, or VAA) for school districts in North Carolina and Tennessee. Sanders grew up on a dairy farm, and attended UT-Knoxville. He used an approach developed by an animal breeder to demonstrate how data could be used for teacher assessment.

Sanders claimed that, “if you use rigorous, robust methods and surround them with safeguards, you can reliably distinguish highly effective teachers from average teachers and from ineffective teachers.”

The Tennessee Value-Added Assessment System (TVAAS) was adopted by state lawmakers in 1992. It was intended to help school directors gauge student progress, or growth, from year to year.

In July 2011, Tennessee became one of the first states in the country to implement a statewide, comprehensive, student outcomes-based, educator evaluation system known as the Tennessee Educator Acceleration Model (TEAM).

Under TEAM, TVAAS counts for 25 to 35% of a teacher’s overall evaluation score, with 15% of the evaluation based on additional measures of student achievement, and between 50 – 60% based on qualitative measures such as observations.

Yet, critics of VAM point out that the models were developed to evaluate populations (of cattle, or teachers) and that the use of tests to evaluate individual teachers has not been scientifically validated.

Valerie Strauss reported in the Washington Post in April that “the American Statistical Association (ASA) just slammed the high-stakes value-added method of evaluating teachers that has been increasingly embraced in states as part of school-reform efforts.”

“These formulas can’t actually do this with sufficient reliability and validity, but school reformers have pushed this approach… Because math and English test scores are available, reformers have devised bizarre implementation methods in which teachers are assessed on the test scores of students they don’t have or subjects they don’t teach.”

“Assessment experts have been saying for years that this is an unfair way to evaluate anybody, especially for high-stakes purposes such as pay, employment status, tenure or even the very survival of a school…Now the statisticians have come out with recommendations for the use of VAM for teachers, principals and schools.” Here’s part of the ASA statement:

VAMs are generally based on standardized test scores and do not directly measure potential teacher contributions toward other student outcomes.

VAMs typically measure correlation, not causation: Effects – positive or negative – attributed to a teacher may actually be caused by other factors that are not captured in the model.

Most teachers say they welcome an evaluation process, as long as it is fair. “Teachers invented tests,” said Andrea Giunta, senior policy analyst in teacher quality for the Washington-based National Education Association. “We’re always looking for feedback because that helps our students learn. But it should be fair and based on sound educational practice.”

But the evaluations, and the consequences, are not always fair, as Farragut 8th grade science teacher Mark Taylor learned over the past few years.

Taylor taught four upper-level physical science courses and one general eighth grade science class, but only the standardized scores of his general science class counted in his TVAAS score. The student scores in his higher-performing upper-level classes, measured by local end-of-course (EOC) tests rather than 8th grade TCAP tests, were not included in his evaluation.

Dr. William Sanders, the creator of TVAAS, has said that the TCAP scores of only one of Taylor’s five classes of students do not fairly reflect his overall effectiveness as a teacher.

The following year, Taylor’s students took both the EOC and TCAP test. But since they had learned the 9th grade curriculum and not the 8th grade curriculum, his student’s TCAP scores fell from an average 98-99% (in 7th grade) to 97-98%, showing negative growth under TVAAS.

Taylor was denied a bonus both years under the teacher evaluation program even though the observation component of his evaluation showed that he was exceeding expectations. Is this how we reward the teachers of our best and brightest students?

Unfortunately, tying a teacher’s evaluation, career path, and even continued employment to a statistical manipulation of test scores has led to some instances of massive cheating and fraud – by teachers and administrators – in cities including Washington DC, Atlanta, Philadelphia, and Chicago, in order to raise test scores to show student improvement and proficiency.

Valerie Strauss wrote recently, “Quite simply, as the stakes rise, so do the occurrences of corruption and distortion. Sadly, education is not immune to this principle…Yet, we march on in the high-stakes test-based accountability era with the high probability that posterity will ask an indicting question of how a generation of educators could commit such offenses when they knew better.”

The good news is one of Education Reform’s biggest proponents of high-stakes testing may be having some concerns. The New York Times reports, “The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation…has called for a two-year moratorium on states or school districts making any high-stakes decisions based on tests aligned with the new (Common Core) standards.”

However, critics of the standards and testing said that a temporary moratorium is not enough. “If the sanctions and punishments tied to test scores are wrong now — promoting teaching to the test, narrowing the curriculum, cheating and gaming the system — the sanctions and punishments will still be wrong two years from now,” said Diane Ravitch, former Assistant Secretary of Education under Secretary of Education Lamar Alexander.

Recent Farragut graduate Ethan Young said in his speech to the BOE last November, “The task of teaching is never quantifiable. If everything I learned in high school is a measurable objective, I haven’t learned anything.” The YouTube video of his speech has over 2.3M views.