The autobiography of James F. Byrnes of South Carolina was appropriately named All In One Lifetime. Byrnes served as a Congressman, U. S. senator, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, Assistant to the President, Secretary of State and governor of South Carolina. Few have ever been so honored as was James F. Byrnes.

James Francis Byrnes was born May 2, 1882 in Charleston, South Carolina. The story of his life was quintessentially American, as James Byrnes’s father passed away shortly after his birth. The death of the elder Byrnes placed the burden of providing a living for the family upon the narrow shoulders of Mrs. Elizabeth Byrnes, who was a dressmaker. There were few opportunities for women during that time and the Byrnes children all went to work at an early age to help out; “Jimmie” Byrnes left his Catholic school to work for a lawyer at fourteen years of age. The enterprising lad learned a trade at that time, becoming a stenographer. Byrnes later became a lawyer although he never even attended high school, much less college. Byrnes received his training as an attorney by the process of reading the law with a mentor, a not uncommon practice at the time. It was sort of an apprenticeship and Byrnes was prosperous enough by 1906 to propose and marry Maude Perkins Busch.

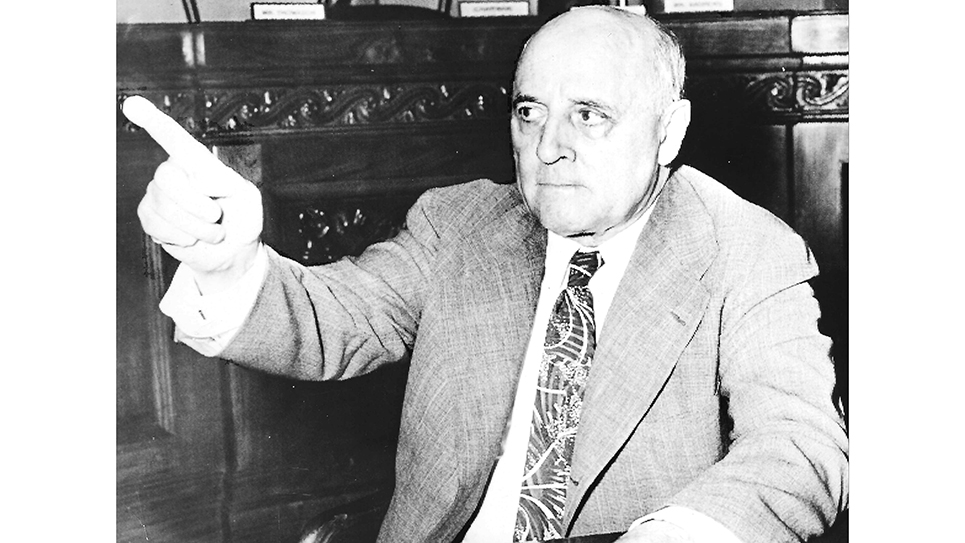

Byrnes became an Episcopalian around the time he married and in 1908 was named solicitor for the second circuit of South Carolina’s courts. By 1910, Jimmie Byrnes was running for Congress and won. Even though he was only twenty-eight years old when he took his seat in Congress, Byrnes proved to have a positive knack for legislating. Thin and wiry, with a craggy face and charming smile, Jimmie Byrnes was unusual for a Southern Congressman. Byrnes relied less on oratory to accomplish his legislative goals than a mastery of moving things along through the committee rooms and halls of Congress. Throughout his career, Jimmie Byrnes became a power in Washington, D. C. precisely because of his ability to work with others. Byrnes also had a propensity to ingratiate himself with those more powerful than himself and despite being little more than a freshman legislator, it was not long before President Woodrow Wilson was entrusting vital tasks to the South Carolinian rather than committee chairmen or more senior Congressmen.

Although South Carolina was a one-party state at the time – – – the Democratic nomination was tantamount to election – – – its politics was hard fought and Jimmie Byrnes decided to run for the United States Senate in 1924. The incumbent was Nathan B. Dial, but Senator Dial had attracted opposition from not only Congressman Byrnes, but also one of South Carolina’s most rugged and able campaigners, Coleman L. Blease.

Blease was one of the most original and perhaps most dangerous of all the famous Southern demagogues of his time. “Coley” was heartily supported by many of South Carolina’s financially disadvantaged, oftentimes referred to as the “wool hat boys”. Blease was an arch white supremacist who heartily approved of lynching.

Senator Dial proved to be a weak candidate and ran a poor third in the Democratic primary. Coleman Blease, a former governor, again demonstrated his vote-getting ability by winning 42% of the vote, while Congressman James F. Byrnes ran second, polling 34% of the vote. Under South Carolina law, the two top vote getters would face each other in a run-off election.

Not surprisingly, Jimmie Byrnes was bitterly opposed by the Ku Klux Klan. Klan members were suspicious of Byrnes as a former Catholic and the rumor that Congressman Byrnes was still a Catholic was spread by the Klan during the run-off election. Just before Election Day, an “endorsement” of Byrnes’s senatorial candidacy by several alleged former altar boys appeared. It was just enough to give Coleman Blease 51% of the vote and the election. It was to be Jimmie Byrnes’s only electoral defeat in a long career.

Out of office, Byrnes moved to Spartanburg, South Carolina where he practiced law. Jimmie Byrnes enjoyed a highly lucrative law practice and one of his confidantes from his Congressional career was immensely wealthy investor Bernard Baruch. Baruch, attracted to the centers of power, provided Byrnes with sound advice on investments, which helped to make the former Congressman wealthy in his own right.

Byrnes was hardly done with politics and while engaged in his law practice and building up his own financial foundation, he found the time to remain involved with South Carolina politics. Byrnes intended to avenge his defeat by challenging Senator Coleman L. Blease for reelection in 1930.

Once again it was a hard fought election and Senator Blease garnered 46% of the vote in the first primary, while Jimmie Byrnes trailed with 38%. Campaigning at a frenetic pace, Byrnes managed to reverse the results of the primary election from six years before, edging out Coleman L. Blease with 51% of the vote.

James F. Byrnes entered the United States Senate on March 4, 1931 and although only a freshman in a body that valued seniority above all else, soon became one of the most important members. Byrnes was an early supporter of New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1932 and after FDR’s election, Byrnes was considered to be the president’s spokesman in the Senate.

As always, superbly skillful, Senator Byrnes used his influence in the Senate, as well as with Roosevelt’s New Deal administration to accomplish a truly impressive feat. For decades South Carolina representatives had yearned for an inland water system, a notion that went back to colonial times. Such a system would help to control severe flooding, as well as increase business opportunities for South Carolina. The Santee-Cooper was pushed by Senator Byrnes who realized South Carolina could not possibly hope to undertake such a project if the state was to provide the money to build it; Byrnes envisioned getting the money from the federal government in the guise of a loan. The idea worked and South Carolina did repay every penny owed without increasing the burden on local taxpayers.

James F. Byrnes was his own man and while he ardently defended and supported President Roosevelt’s foreign policies and many aspects of the New Deal, he dissented when he felt legislation was not in the best interest of South Carolina. Byrnes also tried to dissuade FDR from attempting to purge fellow Democratic senators who had balked at enlarging the Supreme Court as Roosevelt had demanded. One of Roosevelt’s chief targets was Byrnes’ colleague, Senator E. D. “Cotton Ed” Smith.

Smith had served in the United States Senate since 1909 and found just about everything objectionable where the New Deal was concerned. FDR intended to drive Cotton Ed out of the Senate and South Carolina Governor Olin D. Johnston made the announcement he would challenge Smith from the White House steps. Although hardly close, Byrnes quietly made the decision to back Cotton Ed Smith over Johnston.

FDR made a point to travel through South Carolina as the Senate race was under way and made an oblique comment about Cotton Ed, which backfired. Senator Smith, with the help of Jimmie Byrnes, beat Johnston badly.

Having easily been reelected himself in 1936, Jimmie Byrnes was offered an appointment to the U. S. Supreme Court by President Roosevelt in 1941. It was the pinnacle for any lawyer and Byrnes was the last Justice to be named to the court who had not attended law school. Despite the prestige of serving on the high court, Byrnes found himself missing the rough and tumble of elective politics. He would wander back to the Senate, holding court in the office of Leslie Biffle, Secretary of the Senate.

Byrnes only served fifteen months as a Justice of the Supreme Court, resigning a lifetime appointment to accept another job from Franklin Roosevelt as Director of the Office of Economic Stabilization. The United States was fighting a global war after the Japanese Empire had attacked Pearl Harbor and despite the convoluted title, Byrnes held enormous influence over the American economy. As if Byrnes was not busy enough, he was named Director of War Mobilization in 1943. By virtue of his own ability, intellect, and Irish charm, Jimmie Byrnes was exerting enough influence to be referred to as the “Assistant President of the United States”.

A superlative politician, Jimmie Byrnes realized when FDR was seeking a fourth term in 1944, it was unlikely that incumbent Vice President Henry A. Wallace could be renominated. There were vehement objections by many party leaders and bosses across the country who felt Wallace would not only be a drag to the rest of the ticket, but might actually cost FDR votes.

Franklin Roosevelt, distracted by the war, constitutionally averse to telling anyone “no”, and ailing, encouraged the prospective vice presidential candidacies of numerous ambitious Democrats, all while urging the hapless Henry Wallace to seek renomination. One of those Democrats encouraged to run for vice president was James F. Byrnes.

The Democratic National Convention of 1944 would prove to be one of Jimmie Byrnes’s greatest disappointments.