By Ray Hill

Both of Tennessee’s seats in the United States Senate were up for election in 1964, just as they had been thirty years earlier in 1934. Thirty years later, Tennesseans would go to the polls to elect two U. S. senators yet again in 1994.

Senator Estes Kefauver had died suddenly on August 10, 1963 when his aorta ruptured. Governor Frank Clement appointed Herbert S. “Hub” Walters of Morristown to fill the vacancy. Walters was a logical choice to fill a Senate vacancy from the standpoint of service to Tennessee’s Democratic Party. “Mr. Hub” had been a member of the Tennessee State Democratic Executive Committee, as well as Chairman of the state party. A wealthy businessman, Walters had been an active fundraiser for state and national campaigns, including those of Governor Clement and Vice President Lyndon Johnson. Herbert Walters had survived throat cancer, which left his voice somewhat impaired and he was almost seventy-two when first appointed to succeed Estes Kefauver. It seemed unlikely Senator Walters would be a candidate to run for election in the 1964 special election, which felt was precisely the reason Frank Clement had appointed him in the first place.

Clement’s appointment of Walters had given rise to strong rumors in Nashville the governor wanted the Senate seat for himself. Reelected to a four-year term after having been out of office from 1959 – 1963, Clement could not succeed himself as governor in 1966. A seat in the United States Senate would extend Frank Clement’s political life, perhaps for decades. As expected, Frank Clement had announced his candidacy for the U. S. Senate, but met fierce opposition in Congressman Ross Bass of Pulaski, Tennessee. Bass was generally thought to be more liberal than Clement and rallied many of Kefauver’s old supporters to his cause. Once one of the most attractive and compelling candidates in the Volunteer State, Frank Clement lost the Democratic primary badly. Clement polled just under 36% of the primary vote while Ross Bass won almost 51% of the vote. A third candidate, Colonel M. M. Bullard, drew less than 14% of the ballots cast inside the Democratic primary. The scope of Clement’s defeat were staggering to the governor, who was doubtless embarrassed to have lost his own native Dickson County, albeit very narrowly, to Ross Bass. Bass fared much better in his own home county of Giles, where he won quite nearly 70% of the vote. Congressman Bass also won the four big urban counties – – – Davidson, Shelby, Hamilton and Knox.

If Frank Clement’s loss in the Democratic primary was not a surprise to many Tennesseans, the margin was a shock, especially to the governor. The scope of Ross Bass’s victory gave his campaign momentum, although the congressman knew the general election would be hard fought.

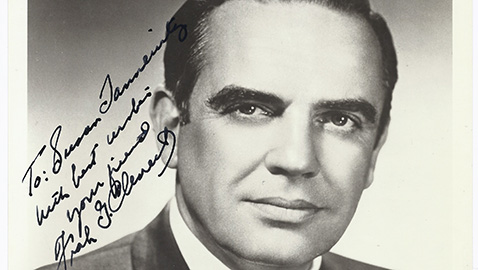

Howard H. Baker had been the congressman from Tennessee’s Second Congressional district since he defeated incumbent John Jennings, Jr. in the GOP primary in 1950. Baker’s personal popularity was demonstrated by his margin of victory over Judge Jennings in the Republican primary; Baker won every county in the district. Baker routinely dispatched his Democratic opposition in the general elections and the congressman had some say in patronage affairs with the election of Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952. In a paid political advertisement appearing in the Knoxville Journal, long-time city councilman and millionaire grocer Cas Walker insisted, “There is no doubt that more Democrats bragged about Howard Baker being their friend than any other Congressman that ever served from this district.” Congressman Howard Baker had died of a sudden heart attack while shaving on January 7, 1964, according to the Journal.

Howard Baker, Jr. was pressed to run to succeed his father in the House of Representatives, but the young attorney had his sights set on the United States Senate. The younger Baker urged his stepmother, Irene, to run in the special election to succeed her late husband. Mrs. Baker was an ideal candidate to keep peace inside the Republican Party, as there would be a hotly contested primary to replace the late congressman. On May 5, 1964, the Knoxville Journal published an article that Howard Baker, Jr. was pondering a bid for the Senate seat held by Herbert S. Walters. Baker admitted he was “seriously considering” running for the United States Senate. “I have learned that some of my friends are circulating qualifying petitions in all nine districts of the state,” Baker said. “I am grateful for this show of confidence.”

Howard Baker, Jr., who along with Bill Brock, certainly deserves the lion’s share of the credit for ushering in the age of a two-party state in Tennessee, told the Journal, “I am also genuinely interested in the opportunity to contribute to the two-party movement in Tennessee.” Frankly, before Howard Baker, there was little “movement” for a vibrant two-party state in Tennessee.

Baker stressed the importance a genuine two-party system to voters in the Volunteer State. “The voters should have a choice of candidates and issues.”

Dr. Charles Moffett of Knoxville, a former member of the Tennessee General Assembly, had announced he would be a candidate for the GOP nomination for the U. S. Senate seat in the special election. On May 26, 1964, Howard H. Baker, Jr. officially declared he would be a candidate for the United States Senate once held by Estes Kefauver at a news conference at the Farragut Hotel in Knoxville. Baker said one reason he had opted to run for the Senate rather than Congress was to eliminate the criticism he was seeking to win election on his late father’s name. Baker said one of his primary goals if elected to the Senate was to improve Tennessee’s economy “without sacrificing our pride and our stature on the altar of political expediency.” Baker stated his belief governments at every level are responsible “to do for the people those things they cannot better do for themselves.” Baker qualified his statement, adding “this must be done within the limits of financial and moral responsibility.”

“I believe that an overall effort must be made to gradually return substantial segments of the government to the local level in order to provide more responsive and more economical administration,” Baker said.

The thirty-eight year-old candidate said the Tennessee Republican Party had not only a responsibility, but a duty “to rise to full maturity and offer to the people of this state the choice of candidates, principles and issues to which they are entitled in the concept of the two-party system.

“The growth of the Republican Party in Tennessee over the past 14 years dictates that the time is at hand to elect Republicans to represent this state in the US Senate,” Baker said.

The Baker campaign began having been meticulously well-organized. As Baker announced his candidacy, a brief biographical sketch and form letter was sent to every newspaper, radio and television in the state. For good measure, a tape recording of Baker’s announcement was sent to every radio station. The medium of television was relatively new in campaigns and Howard Baker would prove to be masterful in appearing on TV. Speaking in smooth and modulated tones, Baker would later win national recognition from the televised Watergate hearings, as did future Republican U. S. senator and Baker protégé Fred Thompson.

The day of those spellbinding orators who could hold the interest and attention of large audiences for hours was coming to an end. It would be replaced by the thirty-second campaign commercial.

Dr. Moffet persisted in his bid to win the Republican nomination for the U. S. Senate, but he lost badly. Even in his own Knox County, Dr. Moffet won only 1,711 votes to 19,005 for Howard Baker. Against two primary opponents, Howard Baker won 93,301 votes to 10,596 for Charles Moffet and 5,947 for Hubert Patty, a Maryville attorney who was well on his way to becoming a perennial candidate for public office. Baker won 20,000 more votes statewide in the GOP primary than Dan Kuykendall who was unopposed. Many counties in Tennessee did not even have a Republican primary on the ballot in 1964.

Lyndon Johnson had succeeded John F. Kennedy as President of the United States following Kennedy’s murder in Dallas, Texas. Johnson embarked upon passing his “Great Society” in Congress, which provided a stark contrast in the Texan’s belief in the scope of government responsibility as opposed to that of his opponent, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona. Senator Albert Gore, seeking reelection to a third term, was a New Deal Democrat who enthusiastically supported the social legislation sought by President Johnson, although Gore was increasingly skeptical about America’s involvement in Vietnam. Congressman Ross Bass, the Democratic nominee for the special election to determine the winner of the seat once held by Estes Kefauver, was also a strong supporter of Johnson’s Great Society.

Howard Baker and Dan Kuykendall may not have presented such a black and white contrast to their opponents as Goldwater did with Lyndon Johnson, but there were certainly profound differences as to how they viewed the role of government in the lives of the people they sought to represent. Baker, somewhat more moderate than Kuykendall, still presented a choice to voters who had concerns about Ross Bass and the congressman’s supposed liberalism. Baker sought to appeal to many conservative and moderate Democrats, especially those rural Democrats, many of whom had supported Governor Frank Clement in the Democratic primary.

The Knoxville Journal quoted prominent local attorney Foster Arnett as saying the Republican ticket of Barry Goldwater, Howard Baker and Dan Kuykendall was the “first clear-cut choice of liberal vs. conservative philosophies.”

Dan Kuykendall proved to be a colorful choice for the GOP standard-bearer in the general election against Albert Gore. Later, Kuykendall would be elected as the first Republican to represent Shelby County in the U. S. House of Representative for eight years. A garrulous man, Kuykendall was often referred to by enemies and friends alike as the “Tennessee Talking Horse.” As Kuykendall and Howard Baker attended the opening of the Republican headquarters in Madison County, local Democrats were astonished to observe some 500 people gathered to support Barry Goldwater and the GOP nominees for the U. S. Senate. Baker urged the audience to vote to end “a 35-year drift toward socialism” as well as return America to “a sound basis of conservatism and Godliness.” Dan Kuykendall predicted 1964 would be the year Tennessee and the South “finally settles down to a two-party system – – – one for conservative Republicans and socialistic Democrats.” Even in Madison County, once a Democratic bastion, there were GOP candidates for the General Assembly who moved through the throng of people shaking hands. Earlier that same day, Dan Kuykendall had told a press conference he was quite pleased with the progress of his own campaign against the wily Albert Gore, later known as the “Old Gray Fox” of Tennessee politics. Kuykendall had officially launched his campaign for the general election in Covington, Tennessee, near Kuykendall’s Shelby County base. Kuykendall reminded newsmen he had already traveled 78,000 miles throughout Tennessee and made more than 500 speeches before winning the GOP nomination. Kuykendall claimed he had found unexpected support for his candidacy in Somerville amongst Democratic officeholders in the local courthouse. Dan Kuykendall flatly opposed President Johnson’s civil rights bill (which Albert Gore voted against), as well as Medicare, which was first proposed by LBJ. Kuykendall was also opposed to certain provisions of Johnson’s anti-poverty program. One federal agency that had Kuykendall’s firm and full support was the Tennessee Valley Authority. When pressed about receiving support from what some news outlets thought to be “extremist” groups, Kuykendall snapped, “To disown them is to admit prior ownership. No one runs Dan Kuykendall . . . not even the Republican National Committee.”

One thing was quite clear: in a state which had never elected a Republican to the United States Senate, the GOP had nominated viable candidates for both of Tennessee’s Senate seats.