The Country Squire Who Became Governor

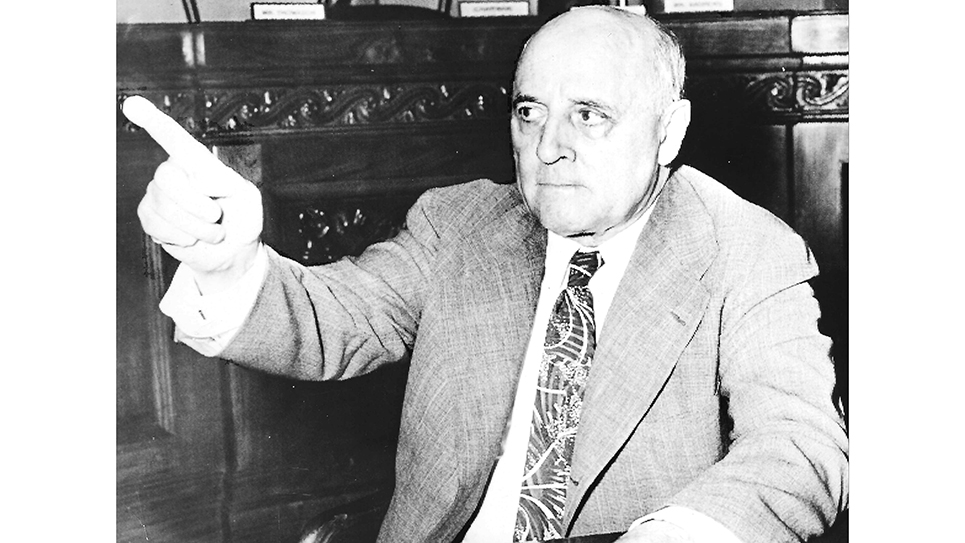

Luren D. Dickinson

As we apparently live in an age of increasingly geriatric candidates for public office, I was interested to note Luren D. Dickinson remains the oldest person to occupy the governor’s office in Michigan. Dickinson was a kindly man of simple tastes, balding and bespectacled with a white mustache living just above his upper lip. Dickinson was a veteran politician although he was not elected governor by the people of the Wolverine State. That came as a distinct surprise to both Dickinson and Michiganders for he was the first man to become governor due to the death of the state’s duly-elected governor.

Seventy-nine years old in 1939, Luren Dickinson answered the old “horn-type wall telephone” at his farm near Charlotte, Michigan. The lieutenant governor had gotten out of a sick bed to answer the telephone and was astonished to hear that Governor Frank Fitzgerald was dead and that he was Michigan’s chief executive. The new governor was inaugurated by taking the oath of office at his modest white-frame house. Only recently had Dickinson given up the old-fashioned “bat-wing” collars and swallow-tail coats he had favored throughout his public career. Although Dickinson was wearing more modern clothes, he never did give up his high-laced shoes.

There were those who said the governorship of Luren Dickinson would be quite an experience for the people of Michigan and it was. The governor issued press releases that were “weekly sermons” on Sundays. Dickinson advised younger men interested in the secret to his own vitality, energy and longevity, “Keep your appetite from being tinkered with. Don’t bewitch it with popular menus, modern dishes, patent cures, or statements of vitamin nuts.” Dickinson liked to remember even then “the good old days” of when family meals had been cooked in the fireplace. Only when he became governor could Luren Dickinson be induced to give up his longtime presidency of Michigan’s Anti-Saloon League. Dickinson stated he did not think it proper for the state’s chief executive to be part of any organization fighting on behalf of a particular political issue. Indeed, it was Luren Dickinson’s devotion to prohibition that caused other candidates to think him a detriment to the GOP ticket, especially in populous Wayne County (Detroit) and other areas where it was hugely unpopular.

To those who thought Luren Dickinson was not a politician, some pointed to his being in the pulpit of a church every Sunday and his constant speaking at county fairs throughout the state and wondered if he ever stopped campaigning.

As governor, Dickinson caused something of a national stir when attending a governor’s conference in 1939, he was critical of one meeting where he claimed it was “a setting for a libertine.” Governor Dickinson said young men and women were encouraged, if not actually plied with strong spirits, where they tottered on “a hellish brink.” While his comments were roundly criticized by some other chief executives, the people of Michigan, used to both Luren Dickinson and his way of expressing himself, just didn’t pay it much mind. A year later, Governor Dickinson readily acknowledged that his language was more abstract than concrete and he was voicing his concerns about what might happen if the young people continued imbibing.

The Escanaba Daily Press remembered Luren Dickinson as “one of the most unusual characters ever to achieve political prominence in any state.” The newspaper marveled at Dickinson’s success in politics without a shred of those attributes most successful candidates possessed. Without the benefit of any kind of formal education and a life-long opponent of “strong drink,” Luren Dickinson was “a man who carefully patterned his life with his religious beliefs” who was “wholly lacking the political qualities that are supposed to make men eligible for the governorship of their state.” Yet for more than four decades, Luren D. Dickinson was one of the most politically prominent men in Michigan.

Throughout his entire life, people were drawn to Luren Dickinson because of his nature. People came away from meeting Dickinson noting his innate kindness and his interest in what they had to say. Dickinson was also a man who possessed an excellent sense of humor and a dry wit. People also noticed Luren Dickinson was genuinely reverent and deeply religious. While tens of thousands of his fellow citizens agreed with Dickinson’s relentless war on “sin and high life practices,” many of those who were more tolerant recognized his sincerity and sense of purpose.

Dickinson had worked hard to earn an education. As a boy he spent his time on the family farm instead of the schoolhouse. Luren Dickinson studied at night and was able to graduate from high school at eighteen because of his own discipline and desire to educate himself. Dickinson’s thirst for knowledge and his reverence for education caused the young man to become a teacher. Dickinson was widely acclaimed by his students and supervisors as a remarkably effective educator and quickly climbed the ladder in the school bureaucracy, first becoming a principal and superintendent of schools at twenty-one. Luren Dickinson married Zora Della Cooley and the couple adopted a daughter and later doted on two grandchildren.

Dickinson’s interest in education ignited his interest in politics, although it would likely be more accurate to state throughout his long career, he was pursued by politics more so than the other way around. Luren Dickinson was just plain well-liked, which was a very good attribute for someone running for public office. Dickinson was also like an old shoe; it shone still when polished and was innately comfortable.

As a temperance lecturer, Luren Dickinson traveled the entire state of Michigan and once elected to the legislature, became one to be reckoned with by many of those who had dismissed him as merely a hayseed or zealot. If Dickinson was openly religious, it was also abundantly clear to most Michiganders that he was also thoroughly honest. In his prime, one Michigan newspaper recalled Luren Dickinson “had 250,000 votes” in the state “in his vest pocket.”

Luren Dickinson became a candidate for and won a seat in the Michigan House of Representatives in 1906, serving a single term. Dickinson ran again in 1904 and was once again elected to the House. After two terms in the House, Luren Dickinson ran for the Michigan State Senate and served one term. In 1914, Luren D. Dickinson was elected to the office he held for the longest time, that of the lieutenant governor of Michigan. Dickinson knew both victory and defeat, running for the lieutenant governor’s office no less than seven times. Dickinson lost two of those races as the GOP nominee for lieutenant governor, as well as one Republican primary for the gubernatorial nomination.

Each time Luren Dickinson lost an election, his political opponents chortled and believed it was the last they would see of him. Invariably, Dickinson would rise once again on the wings of yet another unconventional campaign to win public office, much to the astonishment and chagrin of his political enemies.

When Dickinson had first begun his campaign to reclaim the lieutenant governor’s office in 1938, the Republican leadership in Michigan had dismissed him as too old, would add nothing to the GOP ticket and could not win. Once again, Luren Dickinson won the primary election and while he accused some of his ticket mates of trying to “trade him off” to the benefit of his Democratic opponent, he won the general election as well.

Frank Fitzgerald had been elected governor in 1934 but lost his 1936 reelection bid to Frank Murphy, the mayor of Detroit. Fitzgerald ran a determined campaign in 1938 to take back the statehouse and beat his successor, becoming both the 34th and 36th governor of Michigan. Fifty-four years old when he returned to the governor’s office, Fitzgerald caught a bad case of the flu and died of a heart attack just two and a half months after beginning his second term of office. The man who was “too old” to serve again as lieutenant governor took the oath of office and assumed the governorship. The irony was not lost on Michigan’s Republican establishment.

Once installed as governor, Luren Dickinson engaged in a feud with former Governor Chase S. Osborn. While the two traded public criticisms, each adamantly insisted he admired the other and it was probably true.

Dickinson was one of those rare beings who remained almost an outcast from the political establishment of his party, but who retained a large personal following amongst the voters. After well into his political career, Dickinson was guided by the wise counsel and friendship of Grove M. Rouse. Rouse often traveled to Dickinson’s farm where he purchased maple syrup and dispensed advice. Those familiar with the two men said Rouse was the governor’s closest political and personal adviser. Rouse, who referred to the governor as “Dick,” laughed and told a reporter once, “I’ve been cracked down many times by Dick.” When Rouse was felled by a fatal heart attack in November of 1940, Governor Dickinson openly wept at his friend’s funeral.

In 1940, Dickinson announced he was seeking a two-year term as governor in his own right. The governor swept past six opponents inside the GOP primary easily, although he won with only a plurality of the votes, although he was well ahead of his nearest opponent for the nomination of his party. In the general election, Dickinson faced Democrat Murray Van Wagoner, who had been the Michigan State Highway Commissioner since 1933. Governor Dickinson was running on a strong Republican ticket with highly popular U.S. Senator Arthur Vandenberg and GOP presidential nominee Wendell Willkie appeared to be running well in the Wolverine State.

Willkie edged the greatest campaigner of them all, Franklin D. Roosevelt, in Michigan by just over 6,900 voters out of more than two million cast. Senator Vandenberg beat his Democratic opponent by more than 113,000 votes while Governor Luren Dickinson lost to Murray Van Wagoner by 131,000 ballots. Republicans had been dismayed by Governor Dickinson’s reluctance to ask for votes and when, as required by law, he filed his report of expenditures in the election, Dickinson had spent nothing.

Luren Dickinson loved being governor and it was the apex of his long political career and he chaffed with the disappointment of his defeat. The old veteran campaigner announced as he left the governor’s office that he was retiring from politics. Dickinson was 81 years old and believed he was too old to run for political office again in the future. What the former governor did not know was that he had a very serious and dangerous heart condition.

Dickinson’s defeat may well have been due to his advanced age as much as anything. The governor did appear with other candidates during the 1940 campaign, but there was no hiding his years. Luren Dickinson looked frail and was stooped from his many years. Opponents could attest to Dickinson’s deadly accuracy with a deft and soft-spoken withering comment, although he seldom launched attacks. Luren Dickinson made no secret that he was praying for guidance, and he mostly did as he wished after seeking some direction from the Good Lord.

Luren Dickinson had suffered from a sprained back before he celebrated his 84th birthday on April 15, 1943. A few days later, the former governor suffered a severe heart attack. Dr. H. Allen Moyer, Michigan’s commissioner of health and Dickinson’s personal physician, hurried to his patient’s bedside. Dr. Moyer announced the former governor was “sinking,” but added, “He clings tenaciously to life.” The doctor had just gotten to his own home when he was called back to that of Luren Dickinson. Dr. Moyer sadly pronounced the former governor dead. Dickinson’s adopted daughter and granddaughter, who was named for his late wife, were in the room when Luren Dickinson breathed his last breath. Dr. Moyer said the former governor’s family had not realized just how ill Dickinson really was and attributed death to a blood clot in an artery to his heart.

© 2025 Ray Hill